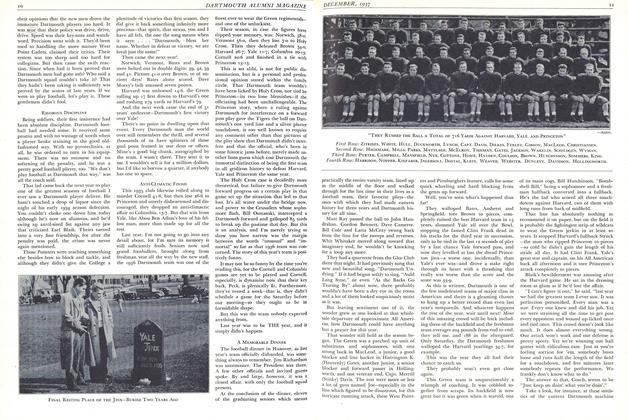

A Standing Salute for the 1938 Team, With Various and Sundry Myths Explained and Exploded

THE IMPRESSIVE and workman- like 14-7 triumph Cornell's truly magnificent football machine registered over Dartmouth's valiantly battling, but completely out-stronged 1938 eleven in Ithaca on Nov. la marked the end of a number of things. It ended the Green's normal football season, for one, the Stanford excursion merely being the pleasant sort of postscript a Dartmouth team can expect, apparently, about once in every 10 years.

It likewise ended Dartmouth's dynastic tenure of No. I honors in the still extremely mythical Ivy League. The Indian hadn't drunk the hemlock since early October of 1936 when the current Holy Cross captain, Bullet Bill Osmanski, raced a brilliant 82 yards with an intercepted Dartmouth forward through the mist and quasi-darkness of a gray Hanover Saturday's twilight.

Between these two crevasses, three Dartmouth varsities had built a bridge of 22 undefeated contests at the expense of Ivy Leaguers and Poison Ivy Leaguers alike. We're forced to whisper, however, that there were three ties in the planking.

But Cornell officially and unequivocally ended the Big Parade.

It likewise ended a myth of national' consequences—the myth of the might and the numerical magnificence of Dartmouth material. If there's any balm in Gilead, this is where we collect it. This, and the further prayer that the smirks and the toxic wise cracks about "Dartmouth's going out and getting 'em" as victory after victory was written into the records, will wither and vanish, as they probably will.

This will come as a shock to some of the brethren at a distance who accept The Saturday Evening Post and similar slick paper ephemerae as something hot from the feed box, but this was one of the weakest, and lightest and most unbalanced Dartmouth squads of many years. In terms of perfection, and likewise in consideration of such sports page headlines as "Minnesota Of The East"; "Leading Teams: Pittsburgh; Dartmouth; Texas Christian etc.," it wasn't a great team. The Holy Ghost and Us Society had something to do with the season, however.

It isn't my intention to make light of sacred things—l said "sacred." I have nothing but the deepest sympathy for a college quarterback torn apart by the merciless struggle to find his own soul. And neither, I want more than to make plain, have I anything but cheers and congratulations for this 1938 Indian eleven.

Bob MacLeod is as fine a back and as great a captain as ever wore the green jerkin, and every man on his team gave more than he had for his coaches and his college. After all, they made history, being the first Dartmouth team ever to score a grand slam over Harvard, Yale and Princeton. They fought the fight in the finest and truest Dartmouth tradition, and even when unescapable defeat was their lot, they battled it out to the last bitter ditch. They drove hard, held their poise, flung themselves savagely at the pounding knees of the enemy, and came out of it, bowed, perhaps, maybe bloodied here and there, but unbroken, unashamed and far from dishonored.

MYTHICAL FRESHMAN TEAM

In fact, they rate a standing salute, and it's the purpose of this piece to tell why. It seems necessary to approach the subject this way, because there's so much in the matter of misleading and unsolicited publicity to undo, before we can even make a start. Never mind how the publicity started. I don't know. Probably a lot of it naturally stemmed from the fact that Dartmouth was undefeated last year, was supposed to have most of the 1937 veterans back in addition to a freshman team, a New York sports columnist quoted somebody as calling "the greatest football team in the United States—college or professional." This got him into an argumentative jam with some of his readers and he dragged the thing out into a protracted and wordy war.

But whatever or however, the word went forth, and every sports page reader was exhorted to "watch Pittsburgh and Dartmouth in the East; Notre Dame in the Middle West; Duke and Tennessee in the South; Texas Christian in the Southwest and either California or Southern California on the Coast."

To those of us close enough to Hanover, geographically, to know what the Dartmouth football hopes really rested upon, headlines such as these were incredible.

To begin with, Dartmouth had the lightest line in the Ivy League, and, although football has changed in a great many strange and fantastic ways, when you start looking at a football machine, you still start with the trench workers. And here was the strange patchwork, one noted in that Dartmouth forward wall:

Left End Whit Miller, that truly great centre, Bob Gibson, Left Tackle Larry Dilkes (lost for the season with a broken ankle bone in the first seconds of the Harvard game), and Right Guard Gus Zitrides, were the veterans—what the sports scribes call "the neucleus." Dilkes had had to be transferred from end because the tackle squad was so undermanned. If big Moose Taylor hadn't left college Dilkes would probably have been his substitute. After Taylor departed and Dilkes broke his leg, George Sommers, who probably would have served the season on the third string became the varsity left tackle—an all important post.

When Soup Campbell, slated to fill the left guard position, had the misfortune to join Mr. Taylor in academic exile, having been taken out of the play by a couple of professors, Lou Young, a sophomore, and son of the former Pennsylvania coach, took over to the best of his inexperienced ability. And in the other tackle post, Jim Feeley, who started his Dartmouth football as a third string right guard, was forced to carry the white man's burden. Jim Parks and Eddie Wakelin shared the right ending job.

This may not make a very clear pattern for the reader, but the gist of it is that with the excep- tion of Gibson, a dependable rather than a: sensational centre, and Zitrides, a great guard for his size, but a little fellow, being a trifle over five and a half feet tall and weighing just over 170 pounds, there wasn't a scintillant star in the troupe and most of them had to be remade by the coaches from something else.

When they finally were assembled, they were inexperienced in spots and they constituted the lightest line, as has been said, in "the league." This was the way they went, names, positions and weights: Miller, le, 180; Sommers, It, 195; Young, Ig, 183; Gibson, c, 185; Zitrides, rg, 172; Feeley, rt, 192; Parks, re, 192.

Behind them was one second string line that fell sharply away in strength. Beyond that were a scattering of strays for every job.

I want to keep making clear that all this is set down in admiration instead of disparagement. It has particular point in view of all the wild talk about "Dartmouth material." One western headline writer called Dartmouth, "The Notre Dame of New Hampshire." Notre Dame, and good luck to 'em, had, this year, three full elevens, none of which really ranked another and, behind these three, a bench populated with 50 good substitutes. The Irish used 82 players in their victory over Kansas, and 35 in their rout of Minnesota where top pressure was on all the way. That will serve to give an idea.

In the backfield was where Dartmouth did have strength, or could have had strength, except for one crippling weakness. Capt. Bob MacLeod is as fine a back as Dartmouth ever had. Perhaps it took this sort of season to prove it. Not to try to penetrate the veil before the war, MacLeod's name belongs in the bracket with those of Robertson, Oberlander and Marsters. It may even rate the No. 1 spot. He could, and did, run, pass, tackle and block. He could kick well enough to get by. He was unhurtable and unstoppable. Speed was the foundation of his entire performance. He tied the world's record in the low hurdles as a school boy out in Glen Ellyn, and although never out for track at Dartmouth because of spring football, he may report for Harry Hillman's team as a sprinter this spring. Along with him in the same backfield were two other sensational ball carriers, Bombshell Bill Hutchinson and Colby (Wild Horse) Howe. Hutch was the best punter at Dartmouth in several years. He likewise was a crack forward passer. Howe was a talented spin-bucker, and a wicked punt runner. He suffered, occasionally from a tendency to fumble, but he more than made up that dereliction with his long sprints down the glory road.

It's when we hit that fourth spot, variously known in these times as "quarterback," "No. 2 back," and "blocking back," that we trip over the lever that braked the whole thing down. In the normal course of events, Harry Gates, would have held that position. He'd been in there for two years and few players in the nation could do the job better. Young Sandy Courter, the sophomore, would probably have been his No. 1 replacement, with Howie Nopper up close.

Gates' renunciation of football forced the coaches to move Courter up prematurely, and the young fellow did nobly all things considered, but he was far from a Gates, and it needed the speed, the strength and the experience of a Gates to let those other speed artists travel at the peak of their capabilities. A Gates likewise was needed to help Bob Gibson back that line.

Eventually Courter was hurt, and Nopper carried on to the best of his considerable ability. Finally the situation was so desperate that the week before the Cornell game, the coaches remade their second string centre, Bob Lempke, a sophomore, into a blocking back, and he started the Cornell game and played most of it in that vital post.

This, then, was the complete picture: a cobbled up line, lacking experience in key positions, and sadly short of weight in the middle, and a backfield consisting of three flaming ball carriers, two of them (Hutchinson and Howe) stronger on offense than defense, only one of whom (MacLeod) was a dependable blocker and no capable No. a back to help, especially, MacLeod get by a good end for a shot at the open.

That line, thanks to Mr. Ellinger's talented coaching, however it was assembled and whatever it weighed, eventually was doing all right. But except for about half of the smashing victory over Yale when Gates made his unprecedented return from voluntary exile, turned the ball game around, almost personally and then sparked the Green to three touchdowns, Dartmouth never did have the full use of her great backfield power.

It was the vision of that team with Gates in there driving and erasing the Yale ends with his powerhouse blocks that showed what this Dartmouth team could have been with the proper sort of fourth operative in that backfield quartette.

It's impossible to discuss the season fully without giving the Gates incident at least a light brushing over, for his absence, in one fashion was the biggest story of the season, until his sudden, unheralded and unprecedented appearance and that constituted a story for almost all time. The spiritual and psychological angles, I'll leave to the better equipped.

In the public prints, when discussing a case of this nature, one necessarily proceeds with a certain restraint. After all, it's the constitutional right of a citizen of this country, and long may it wave!, to worship God, or what he conceives to be God, in whatever form or fashion he sees fit. But in a family discussion of this sort, I hope it's all right to say that this particular case is just downright pathetic.

Alumni at a distance, and even many close at hand, getting the, in many cases, highly idealized accounts from the newspapers, probably have a very hazy con- ception of the entire fantastic affair, and since the football department is involved, it seems only fair to the coaches and officials to spread at least the outline of the picture upon the permanent records, as I see it.

The Holy Ghost & Us Society, which seems to have caused all the trouble, is the spiritual child of a religious eccentric named Sandford, who got the idea back around 1893 that he was the prophet Elijah. He built a place he called Shiloh on a hill near Durham, Maine, where he held private two way converse with the Lord and became a sort of Caucasian Father Divine. The 19th century, for some reason, saw a lot of eccentric religious colonization, starting with the Mor- mons who believed in polygamy; the Zionists, whose Messiah believed the earth was flat, the Benton Harbor Colony of the House of David who decided it was sinful to shave and so on.

The prophet "Elijah" almost missed the boat, so far as the time element went, but he did get going around 1893, and his principal tenet seemed to be that the world was due to come to an end almost anytime now with a flood the size of the one Brother Noah rode out and that the faithful had better give him, or the cult, their goods and chattels, and join him in living in hard work and poverty on the top of a hill so they'd be safe when the waters began to roll. He likewise went in for a little miraculous healing and he tried some dead-raising here and there, so the yellowing clippings in newspaper libraries tell, but his results in the latter field were slightly disappointing.

He finally fell afoul of the law when some of the backsliders and other heirs of deceased faithful sued him over the matter of family funds, and in one of their intimate talks, God told him to load at least part of the faithful on a boat and take them around the Horn to Indo-China or someplace, which, believe it or not, he did. The trip was long. Most of the passengers came down with the scurvy. Many grew seriously ill and as he was eventually taking them past the New England coast and on up into the Arctic upon the advice of the Deity, those able practically mutinied and forced him to turn into the harbor at Portland, Maine.

By this time several were dead. More taken ashore to hospitals died. Some sort of federal law charging criminal negligence on the high seas or some such was invoked against him and he was sentenced to the federal penitentiary in Atlanta for 10 years. Serving seven years of this sentence, he was finally paroled, and, as soon as they turned him loose, he completely and irrevocably vanished. If alive today, and there are those who insist he is alive, he's 76 years of age.

One fable has it that he's living in Boston, where his cult once had a fashionable Commonwealth Avenue headquarters, but if he is, he has the best incognito in history, for my paper fine tooth combed the town for him after the Gates story broke and could locate nothing that even faintly resembled him.

But when he went to jail, his cult went to pieces, and had long since been en- tirely forgotten except by the natives of Maine who live in the vicinity of the once flourishing Shiloh. Although its plant, looking something like a big summer hotel has long since fallen to wrack and ruin, a few of the bewildered originals still putter around the place working the farm and managing, somehow to get by.

SAFE FROM FLOODS

Sandford had two sons and they are said to have made a few feeble efforts to keep the movement alive. Either they, or somebody else, made a militant convert of a gentleman named Holland, who prior to that was quite an athlete at Bates. Holland moved over into the foothills behind Manchester, N. H., established a rattle trap turkey farm on the top of a hill, safe from the threat of that eternal flood, has gathered about him 10 or a dozen shadowy ponderers nobody's been able to interview and has apparently organized a colony patterned after the original Shiloh —a cooperative farming venture with turkeys as the staple.

Somehow or other they got hold of Gates. One story is that they're making a drive for college athletes and telling them the renunciation of the sport they love best is a magnificent sacrifice in the eyes of the Lord and will do a lot toward guaran- teeing them eternal salvation. This seems to square up with Holland's personal story. He was a good athlete at Bates and his "magnificent sacrifice" was walking out of college the night before the Maine Intercollegiates, when he was practically the whole hope of his college to win.

Gates comes from a large family in modest circumstances in the little town of Saugus, Massachusetts, just the other side of Lynn from Boston. His education was made practically a community project. He had run originally with a tough gang of kids and they got into a number of scrapes. Principally through the fatherly interest of the principal of the high school, the treasurer of the town and other kindly local gentlemen, Harrington Gates became not only the pride of the high school but the pride of the town. He ranked with the top of the school in his class work. He was the best half back in the North Shore League.

They told him if he wanted to go on to college, they'd all pitch in and help him. One of the well-to-do men who didn't have a son of his own even said he'd have a good job waiting for him in his business.

After his freshman year in Dartmouth, they were so proud of him that they gave him a little dinner down there one night. I went down and joined in the festivities. He seemed happier about it all than anybody there.

One of the men got him a job driving a milk wagon to tide him over his summer's vacation. He seemed unable to wait to get back to football in the fall.

Whatever happened to him, happened either that summer or early in his sophomore year. By his junior year, the coaches knew they had an unusual problem on their hands and their hearts and they were keenly alert to it. Gates had tried to get other sophomores not to join fraternities, but to join him in the formation of a big religious society. He was a lone wolf on the campus. The other students seldom saw him. Very few knew him by sight.

His marks were well above the average. In fact, he was considered an exceptional student. Football, apparently, was his only emotional outlet. He played it with a savage intensity that made him a star. His terrific blocking and bone crashing tackles seemed to have something more in them than just football.

As time went on the Saugus end of the picture became more and more distressing. It developed that Gates had renounced his family and refused all their efforts to communicate with him. The same went for his friends, the men who had helped him and were still helping him. At the end of the 1937 football season, the town threw a big banquet built around its victorious high school football team, but especial guests of honor were to be the three Saugus boys who had quarterbacked three fine New England elevens last season: Charley Ewart of Yale; Frankie Foster of Brown and Gates of Dartmouth. They were to sit with their fathers at the head table.

The only one who wouldn't, and who didn't, come was Gates.

Frequent efforts to locate him in Hanover finally brought the curt word that he couldn't attend the affair because it wasn't being held in the house of God. It was in the City Hall, as a matter of fact, and the place was packed and jammed on a beautiful snow-frosted night.

NOT COUNTED ON FOR SEASON

Gates didn't show up for spring practice. He was unheard of all summer. It now develops that he was at this turkey farm with the Holy Ghost & Us brethren, but nobody knew that at the time. Not even his greatly disturbed family knew. He didn't show up for the pre-season practice, but he did come back just before college opened, and he proceeded to make himself some funds selling second hand furniture to freshmen in the time honored way.

The season began. There was no Gates. And there never was any Gates until the Wednesday before the Yale game. If he came near the field, nobody saw him. So far as anybody could report, he didn't even come to the early season games.

Through all this the coaches stayed completely away from him. Coach Blaik wrote him one letter saying that the team needed him arid would be glad to see him anytime. The letter went unanswered. Whether students did any nagging at him, isn't part of the record, but the officials respected his right to fight it out for himself.

Why he did come back, eventually, has never been clearly explained either.

He refused to talk about it to reporters. There are all sorts of stories, such as how he first started watching freshman practice, gradually sidled over to the varsity after a few days, and finally said to the coaches, "Let me have a suit."

But however it came about, he came down to the field on Wednesday before the team left for Yale on Friday. He was fit and lean and hard and fast, despite the fact that so far as anybody knows he hadn't had a football in his hands for almost a year, nor had taken anything approximating that form of exercise. For two days he stood around watching while the coaches explained the plays, several of which were new to him. He took his turn driving the varsity at quarterback, and that very first day, he even entered scrimmage for a while, making several hard tackles and reporting that it felt "mighty good."

He went down to the Yale game, so far as anybody knew, principally for the buggy ride. It was generally believed that the first action he'd see would be at Cornell, if he'd even see any then. A year is a long time to stay out of football. A player usually doesn't open cold, as the vaudevillians say, right in the heart of a season. It takes weeks and even months of hard driving preparation.

If you saw the game, or any charts of the game, you know what happened. Dartmouth, expecting a passing game from the Blue, which had been their principal prop and stay against Michigan, Navy and Penn, went into a five man line as soon as Yale took the ball, even though that was in deep Yale territory.

The Yale quarterback, Humphrey, who does all the passing (he threw 30 against Michigan and 27 against Navy) took one look at the Dartmouth setup, saw that the line was only five wide and too tightly spaced, at that, and instead of throwing the cabbage, he started running with it. And he came right down the sward, before that banner throng of 70,000 in five and six and ten-yard slants, slices and sweeps, and almost before the crowd was settled, Yale was on Dartmouth's 30-yard line for first down!

The Dartmouth defence was loose as ashes. Yale had marched almost 60 yards in straight running plays, and the gains were getting longer the closer the Elis got to pay dirt. It looked as if a touchdown were definitely in the process of being born. The harried and bedazzled Green had just taken time out to rally its wits, following a 10-yard end run of Humphrey's, when out from the Dartmouth bench raced a burly figure.

He wore the number 73 on his jersey. There was no No. 73 in the program, but through the binoculars, there was no mistaking that angular jaw and those high cheek bones. It was Gates. I wish I had the space to describe the next half hour of that particular classic's elapsed time, blow by blow. Briefly, however, Yale ran two line plays—two of the sort that had been knocking Dartmouth apart. Both runners went down as if the Bowl had fallen in on them, and got up looking in the same general condition. Both thrusts accomplished a grand total of five yards. Gibson and Gates had piled up the pair of them. Yale then tried .a pass. The ball went wild for Gates had the passer. Yale tried another pass. It, too, clunked the sod unclaimed. Gates had covered the man it was intended for.

So Dartmouth took the ball on downs on her 35-yard line.

MARCH OVER THE GOAL LINE

From that exact spot, with Gates calling the signals in his high piping treble, and with the Dartmouth team suddenly galvanized, rallied and tightened into key, the Green moved straight down the field to a touchdown, although it took the rest of the period for them to make the long trip, goals were switched as they reached the five yard zone and the score was actually made at the beginning of the second period. Some little while thereafter Gates came out, but he had played more than a period.

The Green started the second half with Gates on the bench. The teams battled until Yale ran afoul a holding penalty that hauled them back dangerously close to their goal line. It was evident that they'd have to kick and Dartmouth would have the ball. Gates galloped back into the fray to take over. The kick was a beauty. It came soaring off the kicker's toe back in the end zone all the way across midfield. The Yale line was down under it all the way. The Dartmouth runback was held to five yards and it was Dartmouth's ball on Yale's 47-yard line.

The huddle brought forth Dartmouth's famous and favorite No. 55—the offtackle play. This one went to the left with MacLeod freighting the leather. Gates threw the all important first block at the Yale right end, Moody, erasing him as completely as if he'd never existed. The Green left end, Whit Miller, took the Yale right tackle alone, piling him back in toward centre. Bombshell Bill Hutchinson roared through and took the Yale captain and centre, Bill Piatt, who was backing up on that side. And here came MacLeod, with Howe and the running lineman ahead of him.

All MacLeod needs is a chance—a fissure of daylight no wider than a cigarette paper.

He streamed the 47 yards for a standup touchdown.

The three fastest Yale backs couldn't even get a hand on him.

Some three minutes later, Dartmouth did exactly the same thing again from exactly the same play. This one, however, was of about half the length of the former streamliner, the distance being 2 a yards.

Then the unbelievable Gates went galloping out with a smile as wide as the Bowl on his face. He and Backfield Coach Andy Gufstafson hugged each other gleefully upon the side lines, stood there chatting a moment, and then Gates pulled on his windbreaker and climbed back in with the substitutes.

I go into all this detail for a couple of reasons.

The first is to say that here, and here alone, of the entire season, was the Dartmouth team fully equipped. The way those plays worked were the way they would have worked with a fourth operative capable of the blocking necessary to give those flash backs the requisite help. That half hour was the Dartmouth team at its tops.

The other reason for dwelling at length upon this particular episode is to say that it's probably the first time in all football history that a player, out of football a year, and with practically no training nor preparation in the accepted sense of those terms, ever went into a major football game where early strength was asserting itself and before a monster throng, practically personally turned it around, changing obvious weakness to overpowering strength. Of course, it may be unfair to the rest of the Green players to make such a statement and leave it unqualified. After all they were in their contributing, too. But the facts remain that the plays that were gaining suddenly stopped practically dead, the parade turned the other way and three touchdowns came along with more or less ease.

A football critic seeing that on a movie screen would laugh himself out of his chair.

RETURNED TO FINISH COURSE

If you read the papers, you know the rest of that immediate story, of how remorse for his "yielding to temptation" apparently overcame Gates sometime the next afternoon, of his resignation from college and flight back to the Holland turkey farm, and of how he was eventually persuaded to return to college and finish his- course with the mutual agreement that he wouldn't play any more football.

It was a queer, a difficult and a delicate case, but one can't help but feel that, faced with an unprecedented problem, the college authorities and the football coaches and players, handled it with credit to themselves and with the best interests of the spiritually tortured player ahead of their own, or of the team's.

Dartmouth was a peak football team for one playing half hour.

How, then, did they go so far?

Never discounting the efforts and the accomplishments of the players, who got absolutely all the mileage there was out of a team such as theirs, this team was practically a masterpiece of keen coaching and almost unbelievably accurate scouting. For play-by-play details covering the players' contributions the reader is referred to the eminent Whitey Fuller's "Following the Green Teams" department of this and former issues.

It is my wish to take you behind all that into the conference room with the coaches and especially into the dressing room between halves, after Coach Blaik and his helpers have had a chance to watch the enemy in action for two periods.

Throwing out the Bates and St. Lawrence warmups and starting with Princeton, Dartmouth couldn't go anywhere against the Tigers in the first half. When the players repaired to their quarters at half time, Blaik gave them two running plays to use the second half. When they went back and got the chance, they untriggered the first one. It shot Colby Howe 55 yards to a touchdown. As soon as they got another chance, they let drive with the second one. It catapaulted Bill Hutchinson through Princeton for 68 yards.

Against burly, belligerent and really dangerous Brown, with the day so hot that even the spectators were wilted, the Dartmouth directorate took a long chance, with the score close and started their second team in the second half. These battled the Bruin for more than a period. Then the rested regulars came back and completed the kill. This may not sound like much, under the circumstances, it was really a desperate gamble. That it worked proved that the coaches knew what they were doing.

Harvard offered a knotty problem. The Crimson this year had one of the trickiest systems in the nation. Its plays consisted of a complication of mouse traps, trick shifts and wily deceptions. It likewise could forward pass that football all over the place. Macdonald, Foley and Harding were all dangerous runners. Harvard, in a weird run of luck wasn't winning any games, but it was probably the only team in history that invariably looked better losing than its opponents did winning. It was due to break out. It wanted Dart- mouth especially, since the Green had won four straight in the Stadium.

And the Brown game had shown the Dartmouth coaches some wide and glaring weaknesses, especially in the department of forward pass defense. Their problem resolved itself into one of two choices. They could go in with a backfield composed of MacLeod, Hutchinson, Howe and a blocker and gamble their all upon outscoring the Crimson, or they could weaken their offensive and strengthen their defenses by shifting Hutchinson to fullback, playing Joe Cottone in his halfback spot and leaving Howe on the bench.

The trouble was that Howe, a power house on offense, had been weak against Brown defensively especially in the matter of forward passes.

They ultimately decided upon the defensive game, playing Cottone, shifting Hutchinson and leaving Howe on the bench. It worked. The score was low, leaving some of the blood thirsty disappointed, but 13-7 is as good as 1000-7 so far as the permanent records go.

Against Cornell, there simply wasn't anything to be done. Their great team was simply too big, too heavy, too fast, too powerful, too well stocked with reserves.

It was obvious from the first of the season that if Dartmouth struck a really strong team, having a really hot day, her survival would depend almost entirely upon the breaks, and some pretty miraculous breaks. That lack of one powerful blocker and another savage backer-up to help Gibson was the Indian's Achilles heel.

Shrewd coaching and great bits of individual brilliance carried the lads as far as Ithaca, but here the opposing strength was simply too much. Cornell has a truly great senior team. Their grand line outweighed the Dartmouth line 20 pounds to the man. Their backs were powerful, fast and versatile. They simply took the football and Dartmouth couldn't get it away. When the Green did have it, they couldn't do much. The Cornell line was seldom even off its feet.

Dartmouth fought beautifully, gallantly and to the limit of its strength. MacLeod, Gibson and Feeley shone nobly in defeat.

The Dartmouth coaching staff did make a last desperate effort. In the search for that missing blocker, they changed their second string centre, the sophomore, Bob Lempke into a "quarterback" and started him. The lad did his noble best, and Howie Nopper helped him. But it's doubtful if any team in America could have whipped Cornell that day. They were keyed, they had rested for two weeks. They hit their all time high. Making 18 first downs to Dartmouth's five, rushing the ball 183 yards to Dartmouth's 98 and completing six of 11 passes for 71 yards to Dartmouth's three in 12 for a total of 43, they were clearly the masters, and as such, we freely salute them, the salute coming more from the heart because they are mighty fine people.

MacLeod should, and probably will, make most of the All Americas.

It's something of a shame that this truly magnificent ball carrier had to .spend much of his time his senior season blocking for his mates who couldn't reciprocate. But apparently you either can block or you can't. It must be like playing the violin or wearing a derby. MacLeod could and did. One of his contributions, clearly shown in the movies of that particular pastime, was a remarkable feat in the Princeton game. On and end sweep with the volatile Hutchinson carrying the football, MacLeod blocked the Princeton left tackle out of the way, which was all he was expected to do on the play, but looking up from this job and seeing that Hutch was loose without help, with three Princeton backs angling on him from various stations, the free wheeling Dartmouth captain, dropped his Princeton versus where he was, took out up the field, overhauled his brother halfback just as the situation grew dangerous and with a beautiful flying block, he combed out the dangerous Princeton tackier and Hutchinson breezed on to the long standup touchdown.

These two blocks—get this—took place at points 50 yards removed from each other!

Bob Gibson, the centre, is another who deserves an especially ringing Wah-Hoo-Wah. Josh Davis and Mutt Ray will have to move over. This 60 minute, heavy duty, doubly loaded battler belongs with the best in the list.

And something of the same goes for Battling Gus Zitrides. Feeley was coming fast at the end of the season. So was Lou Young, the sophomore guard. In fact, every man jack of 'em deserves a ringing salute, with two or three more for the coaching staff.

As it chances, I saw . their every major game with the exception of the one at Princeton, and, as I look back on it all, two things I especialy remember. One was the exceptionally smart play of the line against Harvard's hipper-dipper offense. Where Brown, Cornell and Army forwards had been sucked in and murdered on those mouse traps, the Dartmouth line merely held fast and grinned. And when Harvard went into her complicated triple shift that had pulled all the others off side, the Dartmouth team merely rose as a unit and shifted back and forth with them, until from the lofty press tower they looked like two well rehearsed units doing the Lambeth Walk.

That much was smart scouting and expert coaching.

The other memory was the last period of the Yale game. The Dartmouth substitutes were versus the Yale varsity. In fact they'd gone in in the third with Dartmouth ahead by three touchdowns. And even they had walked down the field on the Blue and had added three points to the total with a field goal. Suddenly Yale, fired by the insertion of a sophomore star, who started blinding our seconds with passes, began tp move down the field toward what looked like a coming touchdown.

Blaik turned and summoned his regulars down from the pews, had them strip their sweaters and cluster about him ready to go to the rescue.

And then the Yale stands began to plead in one voice. "We want a touchdown!"

Blaik must have heard them for he seemed uncertain for a moment, but then he turned and sent the regulars back to their roost, while Yale went ahead and flung the touchdown.

The mention of money, of course, is indelicate, but brethren at a distance might be interested to know that Dartmouth again was the biggest gate attraction in this district. The Dartmouth-Harvard crowd in the Stadium was 55,000, the Dartmouth-Yale audience at New Haven, 70,000, the Princeton game crowd was around 45,000, with the World's Series in New York and the Columbia-Army game as competition. The game with Brown in Hanover, sold the place out completely, and the 30,486 customers who jammed into and around the famed Crescent at Ithaca, sold that classic site out completely for the first time in history, being the biggest crowd by 10,000 that ever entered the place. Cornell had to display signs two weeks before the game was due to be played reading, "The Cornell-Dartmouth Game Is Completely Sold Out," and there wasn't a bed to be had within 80 miles of Ithaca. The Harvard and Yale, Ithaca and Hanover crowds were seasonal records by many thousands at each address.

That's the story. The Stanford trip is still ahead as this is written and next year is too far away, to risk any predictions. This team will be historical as the first to take Harvard, Yale and Princeton in the same season. It was a grand group of boys, a credit to the College and a credit to the game.

It hurt, of course, to lose that last one, but there wouldn't be any point in playing, if one team won them all.

COLBY HOWE SCORING FIRST TOUCHDOWN AT YALE

CAPT. ROBERT F. MACLEOD '39

HARRY GATES LEAVING YALE GAME, AFTER SENSATIONAL PLAYING

IMPORTANT MEMBERS OF THE 1938 SQUAD Colby Howe '39, Trainer Roland Bevan, and Bob Gibson '39.

AT THE YALE GAMECoach Blaik shown with Gus Zitrides '39on sidelines.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1929*

December 1938 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

December 1938 By ERNEST H. EARLEY -

Article

ArticleProposed Mew Webster Hall

December 1938 -

Article

ArticlePublications Decision by Trustees

December 1938 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912*

December 1938 By CONRAD E. SNOW -

Article

ArticleGradus Ad Pamassurn

December 1938 By The Editor.

BILL CUNNINGHAM '19

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

November 1941 -

Article

ArticleAND WHAT DOES IT MEAN?

December 1935 By Bill Cunningham '19 -

Sports

SportsTHE NEBULOUS IVY LEAGUE

December 1937 By Bill Cunningham '19 -

Sports

SportsANTI-CLIMATIC FINISH

December 1937 By Bill Cunningham '19 -

Sports

SportsThere Was a Man

December 1943 By Bill Cunningham '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Indian Sharpens Up His Gridiron Tomahawk

February 1949 By BILL CUNNINGHAM '19