Eleven Departments of the Faculty Are Organized To Make Their Interests Effective for Students

[This is the first of three articles describing the Divisions of the faculty—the Humanities, Social Sciences, and Sciences. Professor Dargan has served as chairman ofthe Division of Humanities.—ED.]

LIKE ANCIENT GAUL, the Dartmouth faculty has been divided J into three parts: the Divisions of the Humanities, the Social Sciences, and the Sciences. The province or Division of the Humanities comprises the prefectures or Departments of Art and Archaeology, Biblical History and Literature, Biography, Comparative Literature, English, the Classics, German, Music, Philosophy, Public Speaking, and Romance Languages and Literatures. Among these eleven Departments there must be great diversity of soil, climate, population, and crops; but the eleven are federated by mutual interests and mutual purposes, though the purposes may be hard to define. The chief function of the Divisional organization is to clarify these mutual interests and purposes and to make them more effectual for the education of Dartmouth students.

In most of its affairs, the Division serves as an intermediary or jobbing-house between its Departments and the faculty's Committee on Educational Policy. Although the Division meets and votes as a kind of parliament, its votes are not laws. Any approval which the Division gives to new courses, new majors, or other new measures must be submitted to the Committee on Educational Policy as a recommendation, not as legislation. Such an arrangement seems indispensable because, if each Division legislated for itself, all Gaul might be disrupted.

Undoubtedly, the most definite achievements during the last three or four years must be credited to the Departments individually rather than to the Divisional machine. Since every Department has modified or revised its courses to some extent, I shall merely summarize a few of the more obvious innovations. Among the new courses created since 1934-1935, I can mention two in Biography, "Representative Patriots" and "Representative Autobiographies," and two in Comparative Literature, "The Nature Writers" and "Types of Contemporary Thought." The new major in "Classical Civilization" does not require knowledge of Latin or Greek. A reorganization in the Department of English has provided five different types of major programs and multiplied the courses in American and modern British literature. The Department of Philosophy has increased the variety of its offerings to freshmen and sophomores and has put more emphasis upon philosophical ideas in literature, especially poetry. Through the speech clinic and in other ways, the Department of Public Speaking has provided "remedial work in both major and minor speech difficulties." The Department of Romance Languages and Literatures has evolved new courses in "The Modern Movement" in French literature, "The Spanish Tale and Novel," and under the general caption of "Romance Civilizations." Without knowledge of the original foreign languages, a student can take "Representative French Authors," "The Civilization of Italy," "Spanish Culture and Civilization," and "The Peoples and Civilization of Hispanic America." All the new courses and other changes mentioned in this paragraph have been approved by the Committee on Educational Policy and are now in actual operation.

Naturally, during the past three years, the Committee on Educational Policy (with all respect, let's call it the CEP, to save breath) has not approved everything recommended by the Division of the Humanities. For example, the Division's rather elaborate scheme for "Enlarged Majors" has been tabled to await a more propitious time for such an experiment. In this article for the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, I shall describe some projects which the Division has abandoned, and some which the Division has approved but which are still under consideration by the CEP. But I am certainly not campaigning to influence the CEP's decision. Moreover, I am writing this article on my own responsibility, and the Division must not be blamed for any errors or indiscretions I commit. Sometimes I shall use the language of official reports, in so far as I was one of their authors, and sometimes language licentiously unofficial.

In matters of general policy, much of the preparatory work for the Division is done by its Executive Committee of five members: the chairman, the secretary, and three elected by ballot. During the first year of the Division's existence (19351936) the tasks performed by this committee were pretty dull. We compiled statistics. We found out that an "average" Dartmouth student took 14 or 15 courses in the Humanities, 15 or 16 in the Social Sciences, and about 11 in the Sciences; but many students ranged widely from this average. The statistics proved little except that Dartmouth College dispenses a truly staggering amount of instruction. In the class of 1935, for example (and later classes are much like it), 498 students graduated after taking an aggregate of 7530 courses in the Humanities, 7708 courses in the Social Sciences, and 5653 courses in the Sciences; a total of 20,891 courses. Who shall say whether these figures justify more joy than grief?

The next two years of our labors were livelier. A committee of eight members worked on plans for "topical majors" and things of that kind. We began by considering several proposed changes in the curriculum of the freshman and sophomore years, because any basic change there would affect the whole major program.

Some people have denounced the present foreign language requirement. But that requirement is fairly modest. A student can satisfy it either by continuing for one year the language presented for admission or by taking for two years a language begun in College. This means (except in rare cases) that the foreign lang uages demand no more than six or twelve semester-hours out of the total 120 sem ester-hours required for graduation. In view of this fact, most of us felt that the requirement was hardly so brutal as its enemies imagine, and that it is the minimum desirable in a modern liberal American college while European nations continue to exist and to speak their strange gibberish. Of course there are some students without linguistic ability who nevertheless earn the bachelor's degree; but such men are exceptional and can best be treated as exceptions. To any normal requirement, however carefully framed, exceptions may be necessary—a fact which does not prove that the requirement should be abolished or altered.

We were keenly interested in various plans for an "orientation-course" in the Humanities more or less resembling Social Science 1-2. It has been rumored that such courses are gaining ground in American colleges. They are fewer than we had been led to suppose. The three most significant examples are at Chicago, Columbia, and Reed. After correspondence and study, our committee adopted the opinion that orientation-courses are of two kinds: those taught by one teacher, and those taught by a staff. Under the late Professor Patten, the course in Evolution was energized by his individual ideas and principles. Under Professor Booth, the sections of freshman English which use the textbook EarningOur Heritage have the benefit of Professor Booth's personal enthusiasm for the plan of study outlined by that book. Quite often, a small elective course of this type is excellent because it is unified and vitalized by a single teacher's personality. But a large required orientationcourse is a very different undertaking. At Dartmouth, "Humanities 1-2" would almost certainly have to be taught by a staff of a dozen or twenty instructors drawn from several Departments; and any program on which they could agree might turn out to be nothing better than an insipid and characterless compromise. The scope and subject-matter of the Humanities are so different from those of the Social Sciences that the problem of constructing an introductory course is quite different and probably far more difficult. We cannot be sure that such courses at other institutions have been wholly successful there or would be successful here. Some of us think that the Chicago course in the Humanities attempts too much and the Columbia course too little. Neither one can "integrate" the huge mass of subjectmatter. Furthermore, we may doubt whether "integration" is ever desirable if that abused word means an artificial simplification of ideas and questions whose very virtue depends on their complexity.

Sometimes it seems to me that the student-advocates of "orientation" or "integration" have been bewitched by a totalitarian talisman. Unconscious of their own fanaticism, they are sure that the riddle of the painful earth can be solved by some short-cut to wisdom. Sharing the natural desire of all mankind to get wise quick, they ignore the danger that any collegecourse whose aims are too ambitious may tend either to become dry as dust or to substitute evangelism and propaganda for liberty of thought. We have heard vociferous demands on the part of some students for orientation as well as for other presumed panaceas. But enthusiasm might vanish if the demand were granted. The actual operation on a large scale of any curricular change which disappoints their Utopian hopes might antagonize the enthusiasts and produce a fresh crop of schemes praising fresh avenues to Paradise.

Having reached the conviction that we did not know exactly how to re-model the freshman and sophomore curriculum to our hearts' desire, we proceeded in the Committee on Topical Majors to consider topical majors, as shoemakers try to make shoes. It was more fun. We started off with the idea that interdepartmental majors in the Humanities ought to be based on culture-epochs and should provide four neat topics: (1) "The Classical Heritage," (2) "The Renaissance," (3) "The Romantic Movement," (4) "The Modern Movement." At first, this set-up seemed very nice. There are plenty of courses in our Division and some in other Divisions applicable to these four Topics, and a long list of suitable electives was easily compiled from the College Catalogue. But we had to ask why topical majors are wanted and what function they might serve. We could see no sufficient reason for supplementing or supplanting the present system of Department-majors unless the new interdepartmental majors could provide for the study of selected fields of concentration as important and valuable as the present fields and under conditions not less valuable. Tried by this test, the culture-epoch scheme lost its attractions. We doubted very much whether Dartmouth undergraduates would wish to concentrate on any culture-epoch except the "modern movement"; and the other three so-called "Topics" are certainly more appropriate to scholars than to undergraduate students.

Then we tried to split the Humanities into quadrants to match the presumed special interests of four types of students who would envisage culture from the viewpoints of: 1) the creative artist, 2) the critic or connoisseur, 3) the student of society, 4) the metaphysical thinker,—or 1) the philosophical approach, 2) the historical approach, 3) the religious approach, 4) the artistic

At this point, thank Heaven! the merrygo-round broke down. None of these "approaches", "view-points", or whatever they can be called, ought to be faithfully and patiently maintained for two years by an American undergraduate in his right wits. The function of humanistic culture is not to overstress any single particularized viewpoint or approach, but to encourage and illustrate a balanced variety. If an undergraduate is instigated to dramatize himself for two years in the role of a philosopher, a creative artist, Philo Vance, a Brahmin, or Father Divine, the whole purpose of the major may be wrecked. As one of my colleagues observed: "Departmentalism may be narrow, but no fault in a Department-major can be so bad as the diffuseness and insubstantiality of the Topical Majors we have tried to construct."

But we did not assume that the present system is impeccable. There is no inherent reason why a Department should require a major student to take ten courses in that Department if some courses in other Departments are equally to the point. The present alternative of "combined majors" between two Departments has been somewhat unsatisfactory because administrative responsibility may be indefinitely divided and the student's work ineffectually supervised. After long meditation, our committee became convinced that the natural focus of a major lies within a single Department, but also that some students might reasonably wish for a less intensive Departmental specialization than is now required.

Accordingly, the committee recommended and the Division voted on December 13, 1937, that "the Division approves in principle the creation of Departmental (not Interdepartmental or Divisional) majors requiring fewer than ten courses in the Department and also requiring courses from other Departments within or outside the Division, provided the total number of courses required is twelve, and provided the program of each such major comprises a definite and adequate field of concentration for the student." At a subsequent meeting, the Division voted to elucidate the new proposal by some descriptive paragraphs, of which the following are probably the most important:

"The purpose of the proposed EnlargedMajor is to reduce the present degree ofconcentration... in a single Departmentand to permit... the formation of newMajor programs based, at least in part, onthe cultivation of fields of knowledge notcoextensive with the present Departmentalarrangement of the humanistic studies.

"The proposed Enlarged Majors shouldbe essentially Departmental Majors. Although ranging into several Departmentalfields, they should be anchored to a Department, primarily to give the studentthe basic factual material and method ofthinking of an established discipline,secondarily to ensure a definitely responsible administration without superfluousmachinery.

"A minimum of six semester-courses inthe Major Department should be required,and "in addition to the six (or more) inthe Major Department, the Enlarged Major shall consist of six (or fewer) courseschosen from other Departments in the Division or from other Divisions. Providedthe total number of courses is twelve, theexact proportion of Departmental to extra-Departmental need not be uniform."

Finally, the following statement of policy was adopted on March 7, 1938: "The Division of the Humanities believes (1) that the type of major approved in principle December 13, 1937, will be more satisfactory than any topical majors we could devise for our Division, (2) that the present foreign language requirement is the minimum desirable in a modern liberal college, (3) that no orientation-course in the Humanities taught by a staff from various Departments and comprehending a wide range of informational material should be required of all students."

Though they register a temporary accord, these expressions of belief may be neither unanimous nor permanent. For several years, many members of the Division have hoped that the Executive Committee would seek to define the word "humanities" before making any further effort to reform or confirm the curriculum. I have heard that Professor Nemiah (the present chairman of the Division) and the other members of the present Executive Committee are now engaged in studying the nature and function of the humanities, but I have no right to anticipate or prophesy the results.

Looking back over what I have written, I daresay that readers of this article might censure me for flogging dead horses, in a mare's nest. But, literally, I suppose that the alumni may care to know what the members of the Division have been thinking about as well as what they have voted. The publication of our ideas is unlikely to do any serious harm. Our esteemed noncontemporary The Dartmouth has often grumbled (not without some reason, I think) that elderly pundits and pedagogues are too prone to conceal their doctrines and policies from the profane eyes of modern youth. Also, the pundits and pedagogues are sometimes unjustly suspected of indifference or apathy. The variety of educational projects mooted in the Division of the Humanities during the last three years indicates a mental condition better than pure inert vacuum. Like the editors of The Dartmouth, we dotards really love to hatch swarms of bees in our bonnets. Perhaps one swarm or another may fill the hive with honey and wax,"the two noblest of things, which are sweetness and light."

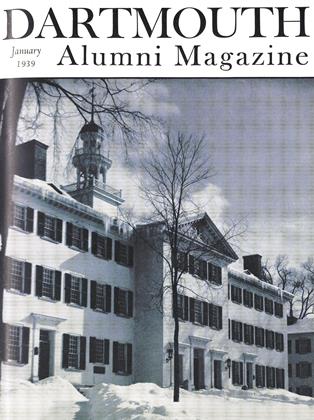

— — HENRY MCCUNE DARGAN Professor of English and author of the accompanying article describing the work of onelarge division of the faculty, The Humanities. Professor Dargan was the first chairman ofhis division under the new plan of faculty organization. The undergi aduate shown aboveis John M. Mechlin '39, an English honors student, son of Professor Mecklin.

ROMANCE LANGUAGES AN IMPORTANT DEPARTMENT OF THE HUMANITIES A corner of the language center on the top floor of Dartmouth Hall. Ramon Guthrie,professor of French, is shown with two students. Offices of faculty members open off thecentral library which serves as a reading and gathering room for language students.

ROYAL CASE NEMIAH Lawrence Professor of the Greek Languageand Literature. Chairman this year of TheHumanities division of the faculty.

PROF. M. F. LONGHURST Chairman of department of music and director of the band and symphony orchestra.

PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

January 1939 By ERNEST H. EARLEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917*

January 1939 By EUGENE D. TOWLER -

Article

ArticleMetropolitan Notes

January 1939 By Milburn McCarty Jr. '35 -

Article

ArticleGradus Ad Parnassum

January 1939 By The Editor -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

January 1939 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January 1939 By Ralph N. Hill '39