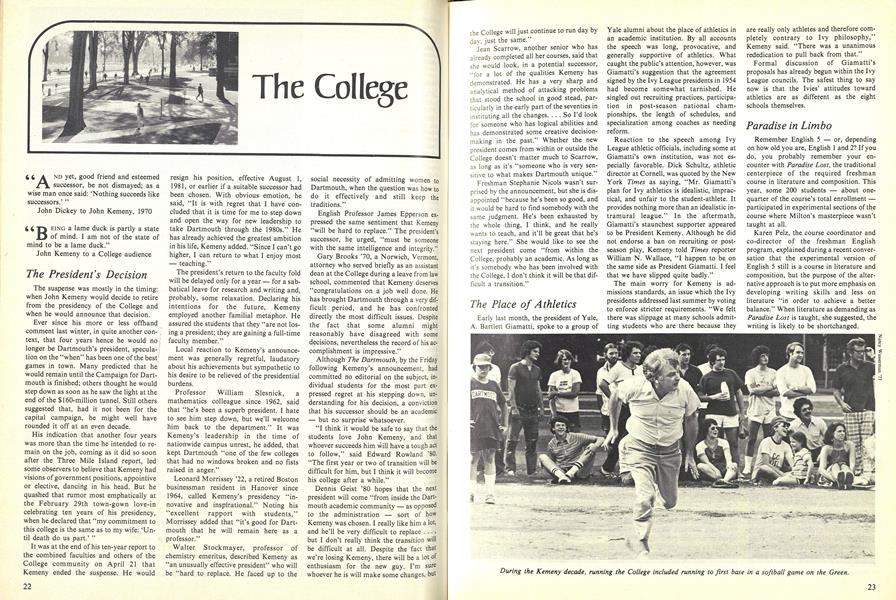

The suspense was mostly in the timing: when John Kemeny would decide to retire from the presidency of the College and when he would announce that decision.

Ever since his more or less offhand comment last winter, in quite another context, that four years hence he would no longer be Dartmouth's president, speculation on the "when" has been one of the best games in town. Many predicted that he would remain until the Campaign for Dartmouth is finished; others thought he would step down as soon as he saw the light at the end of the $160-million tunnel. Still others suggested that, had it not been for the capital campaign, he might well have rounded it off at an even decade.

His indication that another four years was more than the time he intended to remain on the job, coming as it did so soon after the Three Mile Island report, led some observers to believe that Kemeny had visions of government positions, appointive or elective, dancing in his head. But he quashed that rumor most emphatically at the February 29th town-gown love-in celebrating ten years of his presidency, when he declared that "my commitment to this college is the same as to my wife: 'Until death do us part.' "

It was at the end of his ten-year report to the combined faculties and others of the College community on April 21 that Kemeny ended the suspense. He would resign his position, effective August 1, 1981, or earlier if a suitable successor had been chosen. With obvious emotion, he said, "It is with regret that I have concluded that it is time for me to step down and open the way for new leadership to take Dartmouth through the 1980s." He has already achieved the greatest ambition in his life, Kemeny added. "Since I can't go higher, I can return to what I enjoy most — teaching."

The president's return to the faculty fold will be delayed only for a year — for a sabbatical leave for research and writing and, probably, some relaxation. Declaring his intentions for the future, Kemeny employed another familial metaphor. He assured the students that they "are not losing a president; they are gaining a full-time faculty member."

Local reaction to Kemeny's announcement was generally regretful, laudatory about his achievements but sympathetic to his desire to be relieved of the presidential burdens.

Professor William Slesnick, a mathematics colleague since 1962, said that "he's been a superb president. I hate to see him step down, but we'll welcome him back to the department." It was Kemeny's leadership in the time of nationwide campus unrest, he added, that kept Dartmouth "one of the few colleges that had no windows broken and no fists raised in anger."

Leonard Morrissey '22, a retired Boston businessman resident in Hanover since 1964, called Kemeny's presidency "in- novative and inspirational." Noting his "excellent rapport with students," Morrissey added that "it's good for Dart- mouth that he will remain here as a professor."

Walter Stockmayer, professor of chemistry emeritus, described Kemeny as "an unusually effective president" who will be "hard to replace. He faced up to the social necessity of admitting women to Dartmouth, when the question was how to do it effectively and still keep the traditions."

English Professor James Epperson expressed the same sentiment that Kemeny "will be hard to replace." The president's successor, he urged, "must be someone with the same intelligence and integrity."

Gary Brooks '70, a Norwich, Vermont, attorney who served briefly as an assistant dean at the College during a leave from law school, commented that Kemeny deserves "congratulations on a job well done. He has brought Dartmouth through a very difficult period, and he has confronted directly the most difficult issues. Despite the fact that some alumni might reasonably have disagreed with some decisions, nevertheless the record of his accomplishment is impressive."

Although The Dartmouth, by the Friday following Kemeny's announcement, had committed no editorial on the subject, individual students for the most part expressed regret at his stepping down, understanding for his decision, a conviction that his successor should be an academic — but no surprise whatsoever.

"I think it would be safe to say that the students love John Kemeny, and that whoever succeeds him will have a tough act to follow," said Edward Rowland '80. "The first year or two of transition will be difficult for him, but I think it will become his college after a while."

Dennis Geist '80 hopes that the next president will come "from inside the Dart- mouth academic community as opposed to the administration sort of how Kemeny was chosen. I really like him a lot, and he'll be very difficult to replace . . . , but I don't really think the transition will be difficult at all. Despite the fact that we're losing Kemeny, there will be a lot of enthusiasm for the new guy. I'm sure whoever he is will make some changes, but the College will just continue to run day by day, just the same."

jean Scarrow, another senior who has already completed all her courses, said that she would look, in a potential successor, "for a lot of the qualities Kemeny has demonstrated. He has a very sharp and analytical method of attacking problems that stood the school in good stead, par- ticularly in the early part of the seventies in instituting all the changes. ... So I'd look for someone who has logical abilities and has demonstrated some creative decisionmaking in the past." Whether the new president comes from within or outside the College doesn't matter much to Scarrow, as long as it's "someone who is very sensitive to what makes Dartmouth unique."

Freshman Stephanie Nicols wasn't surprised by the announcement, but she is disappointed "because he's been so good, and it would be hard to find somebody with the same judgment. He's been exhausted by the whole thing, I think, and he really wants to teach, and it'll be great that he's staying here." She would like to see the next president come "from within the College, probably an academic. As long as it's somebody who has been involved with the College, I don't think it will be that difficult a transition."

U A nd yet, good friend and esteemed successor, be not dismayed; as a wise man once said: 'Nothing succeeds like successors.' " John Dickey to John Kemeny, 1970 "BEING a lame duck is partly a state of mind. I am not of the state of mind to be a lame duck." John Kemeny to a College audience

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

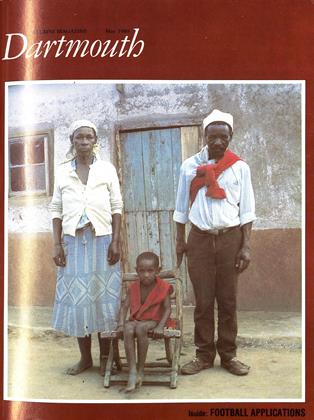

Cover StoryIn Two Worlds

May 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureIn Another Country

May 1980 By Beth Ann Baron -

Article

ArticleAlchemist in Miniature

May 1980 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Article

ArticleScientific Humanist

May 1980 By M.B.R -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

May 1980 By JEFF IMMELT -

Article

ArticlePainting Medicos Have Both "Life" and "Work"

May 1980 By D.C.G