Including aMeditation by Rosenstock-Huessy entitled"Biblionomics." New York: Four Wells,1959. 38 pp. $1.00

During the past two decades the teacher at Dartmouth has been a rarity who has not perceived in at least one of his students deep pedagogical markings of the mind of Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy. Few have been able to take him lightly. Some brought from him to their other academic commitments the attitudes of a roving discipleship. One measure of his influence upon these appeared in a smaller number who reacted against him with an exasperation almost as dedicated. What Rosenstock has taught, out of his deep belief, is properly open to challenge from all quarters. His power as a teacher, for the accepters and the rejectors alike, centered in his clearly declared impatience with the theory that the young mind can learn to conduct itself in controversy through amiable encouragements. He welcomed no challenges from those who had given the problem under discussion no adequate prior thought. Many consequently regarded him as a classroom martinet. Those who could get at least a toehold on common ground have come to know him, outside the classroom, as a patient friend, willing to argue up and down his deep meadow for hours, on or off a horse. This is still happening.

For a special reason I have found it surprising that so few of Rosenstock's colleagues are aware of the large bibliography of his writings prior to his move to America. I once had the task of overseeing the acquisition of his personal library by the College, and its integration into the stacks of Baker. The late Freda Harold, who handled the knowledgeable part of the task with the excellence which in her was commonplace, called to my notice almost daily for a year or two something written by or about Rosenstock, which she had turned up in the course of classifying the Rosenstock-Huessy collection. I got the habit of glancing at bibliographies of likely works in social and political theory, as they arrived in the order department, for evidence of Rosenstock's influence upon other writers. The result was both impressive and depressing. Foreign scholars, particularly in England, were making use of his Out of Revolution (I recall that E. H. Carr was one) but there was almost no sign of its influence in the new land to which he had brought his adventurous learning and his passion as a teacher.

This is a standard if lamentable experience of eminent men. I need not quote the dogeared adage. The other side of the story is rich enough, and the present volume bespeaks the rewards of devotion to the life of ideas which flower up from scholarship. Four of Rosenstock's students have prepared this bibliography of his writings: nearly 150 titles prior to 1935, and about 90 more since his move to America. A few commentaries upon his work by others are included. The range of his interest is phenomenal: in theology from ancient Egypt and China to The Christian Future; in philology from Greece to now, with a pause to work up a medieval Latin grammar; social, political, historical studies in many eras and places; a report for a montaineering journal, a piece on esthetics; studies of Spengler, of William James; above all, the monumental Out of Revolution: Autobiography of Western Man, published in 1938, and the more recent Soziologie issued in two volumes in Germany, 1956 and 1958.

The present volume includes two essays, "Biblionomics" by Rosenstock himself, and a biography of the author by Kurt Ballerstedt: summaries of his career from within and without that should not be further summarized. Professors Carl J. Friedrich of Harvard and Eduard Heimann of the New School supply a brief introduction containing this evaluation:

"There are very few contemporary thinkers of a first rank whose bibliographies would be of equal volume, but what really matters is that in no case can a complete bibliography be as desperately needed as with Rosenstock because the discrepancies between the more or less known and the inaccessible and forgotten parts of the total are so large."

This bibliography is, of course, incomplete: there is more to be written, and recorded in an appendix. The teeming mind that has been so busy at Four Wells cannot be slowed down by the mere suffix "Emeritus."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

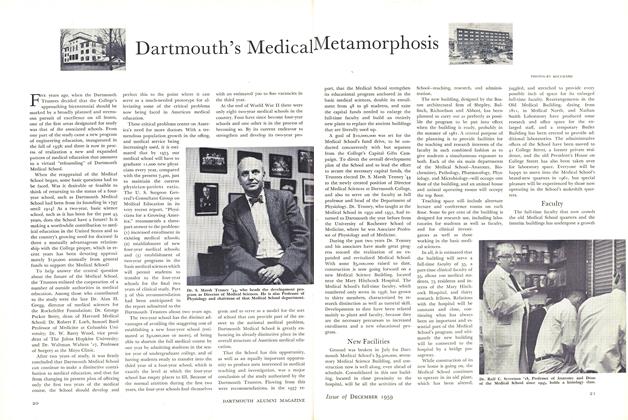

FeatureDartmouth's Medical Metamorphosis

December 1959 -

Feature

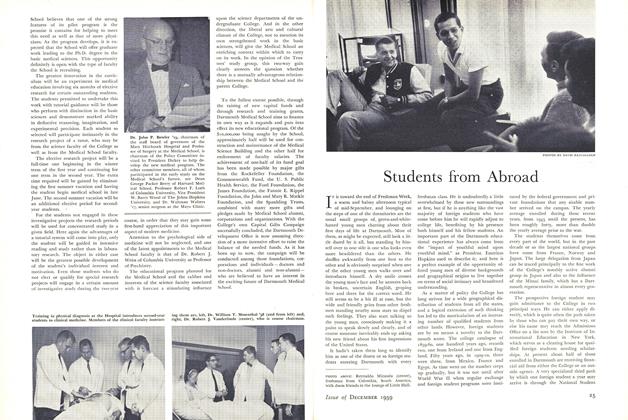

FeatureStudents from Abroad

December 1959 By J.B.F. -

Feature

FeatureMary Baker Eddy and Dartmouth

December 1959 By JOHN B. STARR '61 -

Feature

FeatureSTEFANSSON

December 1959 By ALAN COOKE '55 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

December 1959 By JOHN HURD, LINCOLN H. WELD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1959 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER

ALEXANDER LAING '25

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

June 1940 -

Books

BooksSAILING IN-THE STEREO-BOOK OF SHIPS,

December 1937 By Alexander Laing '25 -

Books

BooksTHE FIVE HUNDRED HATS OF BARTHOLOMEW CUBBINS

January 1939 By Alexander Laing '25 -

Books

BooksHORTON HATCHES THE EGG

December 1940 By Alexander Laing '25 -

Article

ArticleVirtuous Pagan

January 1960 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksASBESTOS PHOENIX.

DECEMBER 1968 By ALEXANDER LAING '25

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF EDWARD GIBBON.

July 1961 By HAROLD L. BOND '42 -

Books

BooksBOUND FOR FREEDOM.

JUNE 1966 By HEINZ VALTIN -

Books

BooksIdiocy and Fantasy

JAN./FEB. 1979 By J. D. O'HARA '53 -

Books

BooksAMERICAN MILITARY GOVERNMENT IN KOREA

October 1951 By John W. Masland -

Books

BooksALGEBRA FOR COLLEGE STUDENTS

May 1937 By Robin Robinson '24 -

Books

BooksTUMOR SURGERY OF THE HEAD AND NECK.

May 1958 By WILLIAM T. MOSENTHAL '38, M.D.