The Crop of Volumes of History in the Making By Roving Correspondents Reviewed and Recommended

I BELIEVE INVINCIBLY that knowledge and peace will triumph over ignorance and war; that the nations will come to an understanding, not to destroy, but to build, and that the future will belong to those who will have done the most to relieve the sufferings of mankind." I regret to report that this was written many years ago by Louis Pasteur (1822-1895), but as it was recently quoted by Paul van Zeeland (one time Premier of Belgium) in a lecture at Cambridge University entitled Economics or Politics there still may be a rift in the clouds over Europe.

Mr. van Zeeland's point was, as I remember it, that the problems of Europe (and the world, too, for that matter) can best be solved by economics rather than by politics or in bloody conflicts between political ideologies. The fact is, he thinks, that the political crisis is really an economic crisis. But is that the whole story? I beg to doubt it. Nations may become psychopathic, after great strain, as do individuals, and psychopaths with machine guns and tanks are highly inflammable. I wish Mr. van Zeeland's optimism might be catching, but most of the commentators that I have read are more pessimistic, and when this appears in print six or seven weeks from now, perhaps we shall know more.

One man's guess to-day seems to be as good as that of an expert. We are in a curious state. A scientist (or even an undergraduate) may predict with reasonable certainty a reaction, let us say, of sulphuric acid on copper, but who can predict the way of a maid with a man, or the working of a dictator's mind? particularly if the dictator is fired with pure hatred for the Jews (see Vincent Sheean) and messianic delusions of grandeur for himself, for his country, and for his race? It is not surprising that the rational and compromising English (led by a Birmingham industrialist, who, although somewhat cadaverous in appearance, must in reality be alert to the dangers confronting the British Empire) had believed for a short space of a midsummer's dream in the rationality of the Munich Pact. Surely the Axis powers would listen to the voice of reason. But one man's reason may be another man's poison, and some months later Mr. Chamberlain was forced to conclude that England must fear God but take her own part (that is with the help of France and the despised Communists in Russia and perhaps, also, the United States). And so a year later eight million men are mobilizing.

There has been War for a long time, but England took a long time to recognize that fact. Just a year ago I heard a member of the History Department of Dartmouth College predict that war was, he feared, inevitable within a day or two. It did not come in the form we have always understood War; now they call it a War of Nerves. Perhaps it will not come this year, but most commentators still see it as inevitable. Not, however, Mr. van Zeeland. It would not come of course if men and governments were governed by reason, but when they are moved by the instincts and passions of the lower anthropoid orders (biologically speaking), admitted by Hitler in his preposterous but dangerous MeinKampf I am afraid we can expect real trouble. Mr. Roosevelt and Mr. Hull, both in my opinion reasonably able men in foreign affairs, fear the worst. Idealistic senators (Mr. Gerald B. Nye) and certain Ward Politicians in the Senate believe otherwise. I trust that they are right, for their responsibility is a grave one. History may or may not vindicate the Chief Executive's gift of prophecy, but one thing reasonably certain is the fact that if Europe joins Asia in a War, the United States will be scorched, if not burned, and I agree with the Administration's Policy that anything done, or said, now, to prevent war is an altogether sensible thing. I wish I could believe in the good faith of modern governments, but after one has observed the evils perpetrated by both the democracies and dictatorships it is difficult any longer to be so naive. This is one of the strong points in Vincent Sheean's Not Peace But a Sword which is written with a fine indignation and with a keen sense of the Machiavellian realities in a mad and wicked world.

History to-day is being written by journalists who have been roving correspondents, who have interviewed the international big shots, and who presumably should know what they are talking about. But I find after reading many of their books (often best sellers) that I am still sceptical of their infallibility. Truly enough they are entertaining, and in Sheean's instance, vastly moving; they exhale a fine scorn and a righteous indignation, but whether they have an adequate historical background, to judge infallibly, is another matter. In their claims they are modest enough but the public have been led to believe that if they wish to know the inside story, or the really hot news they must rush and buy one of the many current accounts by journalists. This may be sensible but in the long run I should prefer to put more trust in such a book as Mr. Raymond Leslie Buell's Poland: Key to Europe (Knopf, 1939) which is a statistical and historical analysis of Poland's relationship to Europe past and present. The author has had long service as president of the Foreign Policy Association, and unlike most of our journalistic historians he does pull a punch now and then so far as prophecy is concerned. He believes, after a long and searching study of Poland, that she must first surmount her internal difficulties, which Mr. Buell analyses without guess, prejudice, or indignation, if she is to resist successfully German aggression and remain an independent nation. She needs help in her struggle, and apparently will get it. This is a businesslike volume covering relatively a small territory.

Let us now turn to John Gunther. In one volume he covers the affairs of China and Japan, and all countries westward as far as the Mediterranean. Incredible, Watson! And yet, in Inside Asia, Mr. Gunther has done an admirable job, with the assistance of a corps of helpers, and many books, in summarizing for the average reader the history, point of view, present status and so on, of Japan, China, India, the Dutch East Indies, Singapore, Iran, Iraq, Arabia, Palestine, the Kamchatka Peninsula, Harbin, Manchuoko, Inner and Outer Mongolia, Hanover, New Hampshire and Norwich, Vermont. (I guess I am getting him confused here with Walter Wanger '15.) Mr. Gunther travelled 30,000 miles through the East and interviewed many people. However, most of his information he, and others for him, gathered from many books on Japan, and so forth. The constant student of Eastern affairs will find recalled here many things he has forgotten, and some that will be new. To the great American reading public each page may well prove a revelation. It is a highly instructive book, and entertaining in the best journalistic fashion. Mr. Gunther maintains successfully, I think, an objective attitude in the many complex problems he so clearly presents. I found most interesting Chapters 31, King of Kings; the Shah of Iran (Persia); 32, The Story of Ibn Suad (The Arabian World); and 35 on Dr. Weizmann and the Zionist Movement. If you have already read Agnes Smedley, Edgar Snow, Reginald F. Johnston, Hallet Abend, W. H. Chamberlin, and others (most of them previously reviewed here) you will not find much that is new about the Far East, but the book deserves the wide reading it is receiving. It is timely, but not profound in any sense, nor has the author intended it to be.

In Graham Hutton's Survey AfterMunich (Little, Brown & Co., 1939) the author attempts "to discover to what extent Germany, after peaceful and spectacular victories in 1938, can Europe's destinies." The author presents a dispassionate analysis of the New Europe which is being moulded on the farther side of the Rome-Berlin front: the new Czecho-Slovakia, Hungary, Poland, Rumania, Jugoslavia, and the Balkan Peninsula. It is clearly written, and seems judicious and sensible throughout.

The most interesting and entertaining of all the journalistic accounts of a nervous Europe that I have read is Pierre van Paasen's Days of OUT Years (Hillman, Curie, 1939). The author writes with a Swiftian point of view, conscious throughout of man's inhumanity to man, and he tells some incredible stories, such as Hitler's plan of 1934 to obliterate Paris suddenly from the air, which his Axis partner Mussolini couldn't stomach thus earning the cooperation as regards sanctions with the French statesman Laval, the story of the haunted house, the black dog, and so on. His account of modern slavery in Africa has the ring of truth. The more evil the situation described the easier, in the Christian era 1939, it seems to believe. For corroboration see Sheean's Not Peace Buta Sword.

Valentine Williams' World of Action (Houghton, Mifflin, 1938) describes the life of a European newspaperman (Reuters) from before the Great War and after. Mr. Williams has since become the creator of the character Clubfoot in several thrillers. Worth reading.

Also recommended: We Cover theWorld, by 16 Foreign correspondents.

The author of Night Over England (Harrison-Hilton Books, 1939), Eugene Lohrke, is an American who has resided in a Sussex cottage for the last three years with his wife who collaborated on the book. In this report he gives his version of Great Britain's conduct during the current and prolonged crisis (a contradiction in terms). Let me quote: "I don't so much mind being killed as always being deceived. I'm an old man and my time has come, but I want to know where I stand and what I'm standing for, don't I? and that's about how everyone feels." Another: "For the first time in my life I'm ashamed to be an Englishman." Still another: "What right have we to sell out our neighbors? Who's going to trust England again if we act like this?" These remarks reflect the way the average Englishman feels, argues Mr. Lohrke. His thesis, not new anymore, is that the Tory government of Mr. Chamberlain and the Tory newspapers prefer Fascism and so avoid a showdown. (They are afraid of a rise of Labor.) Then, when almost too late, they discovered the malignity of the Hitler Mussolini philosophy. England seems to the author to be in the twilight of her day but most Americans still see England romantically as a place of lush green fields, castles, and hallowed shrines. This is an honest appraisal but perhaps the tide has now turned for the better. Highly recommended.

[Mr. West's copy was prepared some timein advance of the Labor Day week-endclimax to the European crisis.-ED.]

PROFESSOR OF COMPARATIVE LITERATURE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThis Too Will Pass

October 1939 -

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

October 1939 By The Editor -

Article

ArticleFriends of France

October 1939 -

Article

ArticleHakluyt in Hanover

October 1939 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Article

ArticleIn Memoriam: W. B. D. H.

October 1939 By FRANKLIN McDUFFEE '21, Anton A. Raven -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912*

October 1939 By CONRAD E. SNOW

HERBERT F. WEST '22

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

November 1934 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

May 1936 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

October 1937 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

June 1939 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksTHE WINOOSKI,

June 1949 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

June 1955 By HERBERT F. WEST '22

Article

-

Article

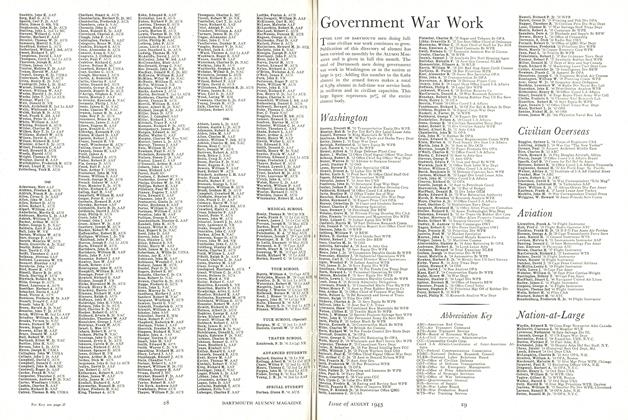

ArticleAviation

August 1943 -

Article

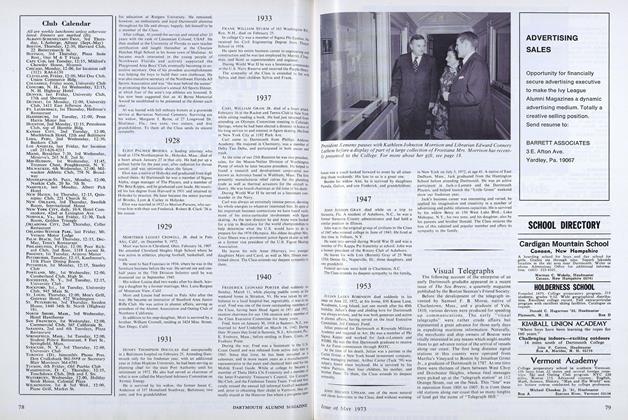

ArticleVisual Telegraphs

MAY 1973 -

Article

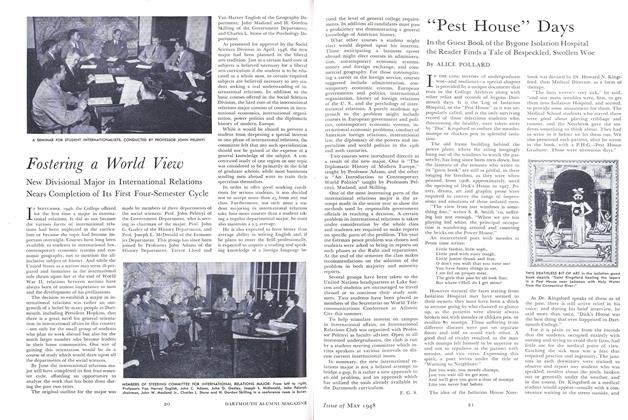

Article"Pest House" Days

May 1948 By ALICE POLLARD -

Article

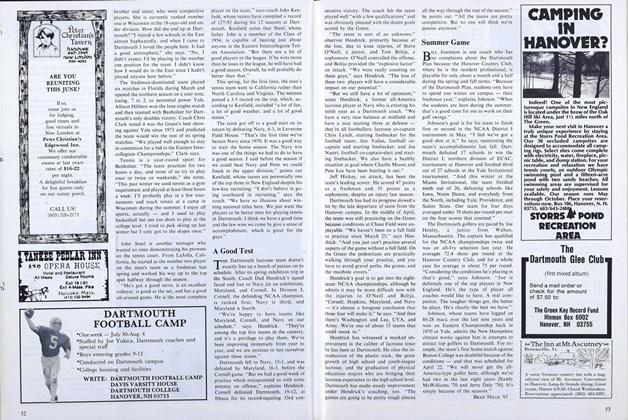

ArticleSummer Game

MAY 1978 By BRAD HILLS '65 -

Article

ArticleATHLETIC POLICY OF THE COLLEGE

August 1917 By HORACE G. PENDER -

Article

Article“I Could Have Danced All Night...”

JUNE 1990 By Jim Boldt ’35