THE WORLD OF BOOKS

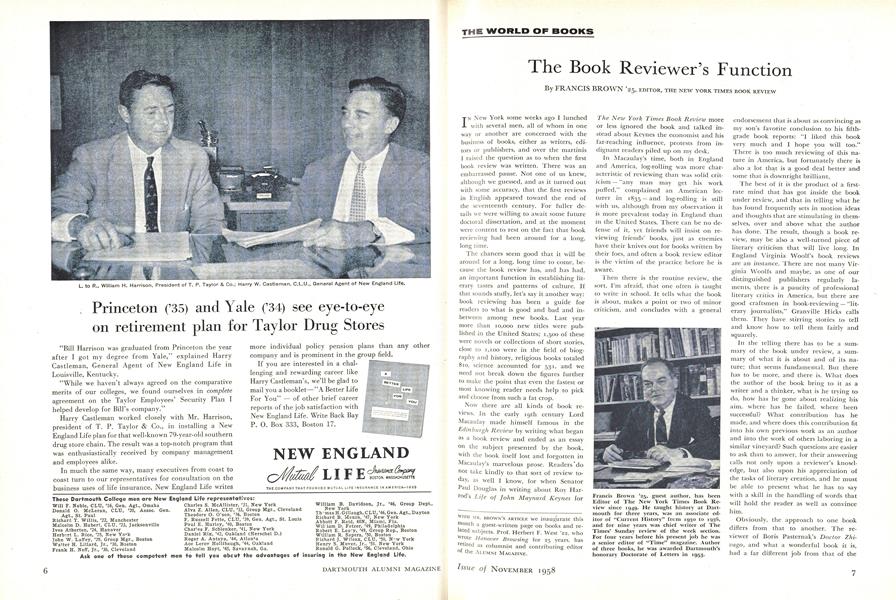

EDITOR, THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

IN New York some weeks ago I lunched with several men, all of whom in one way or another are concerned with the business of books, either as writers, editors or publishers, and over the martinis I raised the question as to when the first book review was written. There was an embarrassed pause. Not one of us knew, although we guessed, and as it turned out with some accuracy, that the first reviews in English appeared toward the end of the seventeenth century. For fuller details we were willing to await some future doctoral dissertation, and at the moment were content to rest on the fact that book reviewing had been around for a long, long time.

The chances seem good that it will be around for a long, long time to come, because the book review has, and has had, an important function in establishing literary tastes and patterns of culture. If that sounds stuffy, let's say it another way: book reviewing has been a guide for readers to what is good and bad and inbetween among new books. Last year more than 10,000 new titles were published in the United States; 1,500 of these were novels or collections of short stories, close to 1,100 were in the field of biography and history, religious books totaled 810, science accounted for 531, and we need not break down the figures further to make the point that even the fastest or most knowing reader needs help to pick and choose from such a fat crop.

Now there are all kinds of book reviews. In the early 19th century Lord Macaulay made himself famous in the Edinburgh Review by writing what began as a book review and ended as an essay on the subject presented by the book, with the book itself lost and forgotten in Macaulay's marvelous prose. Readers'do not take kindly to that sort of review today, as well I know, for when Senator Paul Douglas in writing about Roy Harrod's Life of John Maynard Keynes for 7 he New York Times Book Review more or less ignored the book and talked instead about Keynes the economist and his far-reaching influence, protests from indignant readers piled up on my desk.

In Macaulay's time, both in England and America, log-rolling was more characteristic of reviewing than was solid criticism "any man may get his work puffed," complained an American lecturer in 1835 - and log-rolling is still with us, although from my observation it is more prevalent today in England than in the United States. There.can be no defense of it, yet friends will insist on reviewing friends' books, just as enemies have their knives out for books written by their foes, and often a book review editor is the victim of the practice before he is aware.

Then there is the routine review, the sort, I'm afraid, that one often is taught to write in school. It tells what the book is about, makes a point or two of minor criticism, and concludes with a general endorsement that is about as convincing as my son's favorite conclusion to his fifthgrade book reports: "I liked this book very much and I hope you will too." There is too much reviewing of this nature in America, but fortunately there is also a lot that is a good deal better and some that is downright brilliant.

The best of it is the product of a firstrate mind that has got inside the book under review, and that in telling what he has found frequently sets in motion ideas and thoughts that are stimulating in themselves, over and above what the author has done. The result, though a book review, may be also a well-turned piece of literary criticism that will live long. In England Virginia Woolf's book reviews are an instance. There are not many Virginia Woolf's and maybe, as one of our distinguished publishers regularly laments, there is a paucity of professional literary critics in America, but there are good craftsmen in book-reviewing - "literary journalists," Granville Hicks calls them. They have stirring stories to tell and know how to tell them fairly and squarely.

In the telling there has to be a summary of the book under review, a summary of what it is about and of its nature; that seems fundamental. But there has to be more, and there is. What does the author of the book bring to it as a writer and a thinker, what is he trying to do, how has he gone about realizing his aim, where has he failed, where been successful? What contribution has he made, and where does this contribution fit into his own previous work as an author and into the work of others laboring in a similar vineyard? Such questions are easier to ask than to answer, for their answering calls not only upon a reviewer's knowledge, but also upon his appreciation of the tasks of literary creation, and he must be able to present what he has to say with a skill in the handling of words that will hold the reader as well as convince him.

Obviously, the approach to one book differs from that to another. The reviewer of Boris Pasternak's Doctor Zhivago, and what a wonderful book it is, had a far different job from that of the reviewer of Peyton Place, just as a reviewer tackles differently a journalistic biography of Mrs. Roosevelt and a scholarly life of Woodrow Wilson, or a volume of Phyllis McGinley's light verse and a collection of T. S. Eliot. Each book has to be judged on its own ground, within its own frame of reference. One does not apply the standards of War and Peace to a volume of summer fiction.

A good book review can be an exciting thing. It may lead a reader to a book and make him read, and that, of course, is the hope of its author and publisher. But the review in itself has the excitement of discovery, for the reviewer is setting forth what he has found in a book, and if the book is a good one, he has found a lot, whether it is new understanding of the human animal or fresh interpretation of the facts of history or new insight into the workings of the marketplace. He shares his discoveries with his reader. Sometimes readers may be outraged by his findings and his comments on them, but so much the better, for dissent in itself is exciting, and how dull it would be to find ourselves always in agreement — in politics or aesthetics or in modern collegiate architecture.

Yet the basic purpose of a book review remains what it has always been: to inform the reader about new books and to help him select intelligently the ones he wants to read. If in the process he has been not only informed, but challenged, stimulated, why that's a welcome dividend, but no book review editor gives house room to the worn-out witticism, "Have you read any good book reviews lately?" He wants his readers to read the reviews, of course. He wants even more that they should read at least some of the books reviewed. He believes books to be important. That's why he's in the business.

Francis Brown '25, guest author, has beenEditor of The New York Times Book Review since 1949. He taught history at Dartmouth for three years, was an associate editor of "Current History" from 1930 to 1936,and for nine years was chief writer of TheTimes' Sunday review of the week section.For four years before his present job he wasa senior editor of "Time" magazine. Authorof three books, he was awarded Dartmouth'shonorary Doctorate of Letters in 1953.

WITH MR. BROWN'S ARTICLE we inaugurate this month a guest-written page on books and rented subjects. Prof. Herbert F. West '22, who wrote Hanover Browsing for 25 years, has retired as columnist and contributing editor of THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

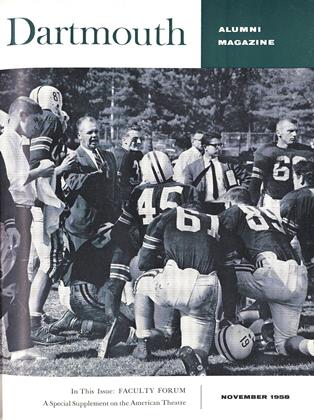

FeatureWhere Are the Silver Cornets? or Twenty Versts to Nizhni Novgorod

November 1958 By KENNETH ALLAN ROBINSON -

Feature

FeatureHow Firm a Foundation?

November 1958 By PROF. HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Feature

FeatureFive Wishes for America

November 1958 By BENFIELD PRESSEY -

Feature

FeatureA Community of Learning

November 1958 -

Feature

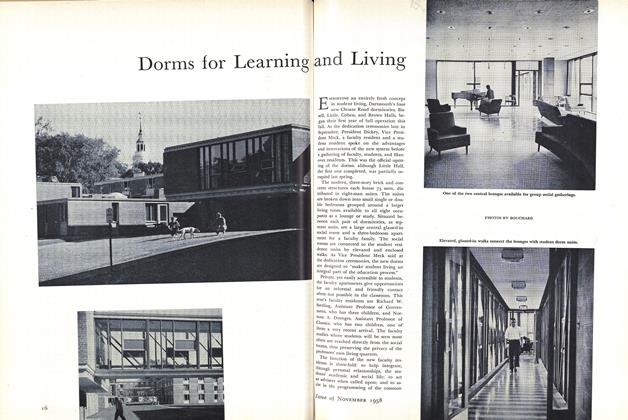

FeatureDorms for Learning and Living

November 1958 By J. B. F. -

Feature

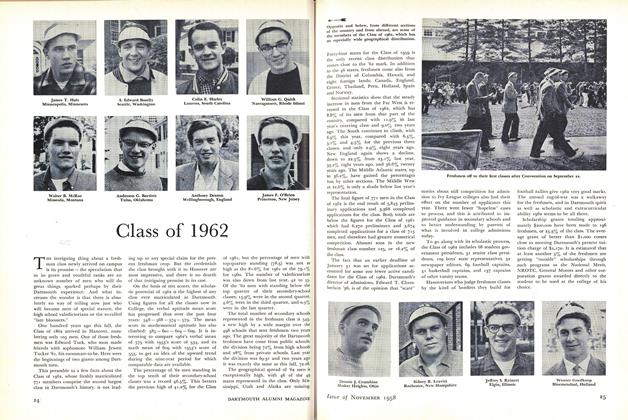

FeatureClass of 1962

November 1958

FRANCIS BROWN '25

Article

-

Article

ArticleHAWLEY '09 AND LLEWELLYN '14 COACH

October 1919 -

Article

ArticleDRYFOOS MEMORIAL

OCTOBER 1963 -

Article

ArticleThe Fund

SEPT. 1977 -

Article

ArticleAddressing Success

Jan/Feb 2004 By Alice Gomstyn '03 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

December 1959 By EDWARD S. BROWN '35 -

Article

ArticleFriends of Baker Library at Dartmouth

April 1938 By Herbert F. West '22.