Biographical Portrait of William Kilborne Stewart, Dynamic Influence Throughout Forty Years of Dartmouth Teaching

DURING FORTY YEARS Professor W. K. Stewart (known as Bill Stewart to his friends and contemporaries) has taught thousands of students who have passed through the halls of Dartmouth. In all these years what has this great teacher accomplished? As one of his students, and for fifteen years his colleague, I shall attempt to answer this difficult question. It is not an easy question to answer, and it would seem to be well worth the asking. Any conscientious teacher must often ask himself just what his years of study, his reading, writing, and thinking, his intensity of spirit lavishly expended in lecturing to interested and uninterested students, accomplish?

Not all teachers follow the same technique in their life's work. Many prefer scholarly research and subsequent publication (often unreadable), in which case teaching becomes secondary and undergraduates merely a necessary evil of life; others coast along, secure in their positions, and take life as easily as a country gentleman should. Still others teach with an evangelical fervor, moved either by an inner voice or by the "exuberance of their own verbosity." Mir. Stewart belongs in none of these groups. Many years ago as an undergraduate I wrote an article for the now defunct Bema on a man for whom Diogenes had been so long seeking: an honest man seeking with his whole heart and brain the simple (or complex) truth. This essay concerned my own teacher, W. K. Stewart. The time was shortly after the World War. I am now more confirmed in this early opinion of him than ever.

I found in Professor Stewart a teacher whose primary instinct was to stick to the facts. He gave both sides of every question in a calm manner, and in extremely lucid English. I have never known a teacher who could so clearly expound a difficult philosophical, economical, or literary hypothesis. There were no hysterics, few fireworks. There certainly was often a subtle and ironic sense of humor, examples of which I must omit. Along with this sense of humor there was always a spirit of Montaignian tolerance. Mr. Stewart has nourished himself on the great French and English rationalists, and he has always believed in the potential powers of reason. Intellectually curious himself, he was generally able to instill this essential quality into his students. He literally incandesced in his desire for truth wherever it might lead him. There are many who can rationalize ugly facts or truth away (as witness Leibnitz and Pope), but never did Professor Stewart do so. The essential quality of his mind is that of a singularly simple, but noble, probity. It is generally a sign of literary weakness to indulge in superlatives but it is merely stating a fact when I say that Mr. Stewart has long had the reputation at Dartmouth of being the most erudite man on the faculty. Be that as it may a life time of reading in many languages, an acute intellectual curiosity about all things, has given him an almost unrivalled amount of learning. Nor is this all. During his many years here he has been father confessor to many, both among the faculty and the students, and even in the administration. He has had the confidence of the official college as have few men in his time, and his character is such, that people gravitate toward him naturally, but what has this teacher really accomplished in his forty years at Dartmouth?

INTANGIBLE ACCOMPLISHMENT

Certainly he has never taught a man how to make .more money, or to gain a position in society: He has been dealing all his life with the intangible qualities of mind and heart. Qualities which really do enrich one's personal life. One must be a better man for having sat in one of W. K. Stewart's classes, more tolerant, wiser (though wisdom comes with age), intellectually curious, and with a far wider knowledge than ever before. He may, too, have gleaned something still more precious, friendship with a simple, and an honest spirit.

William Kilborne Stewart was born in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, on January 2, 1875, the only boy in a family of three girls. He is of Scottish, English, and New England ancestry. His mother, Augusta Kilborne, was of English and New England stock coming from an early Empire Loyalist family. From her Professor Stewart inherited his temperament and generous character. Although she was a strict Baptist she was the most tolerant woman that Professor Stewart has ever known. She died in 1911. His father, a Baptist minister, was born in the lowland village of Ecclefechan, Scotland (birthplace also of Thomas Carlyle), and he graduated from the University of Glasgow about 1858. He came to America at the age of twenty one, and served as pastor of several parishes in Ontario, Tennessee, California, and Kentucky, and while living in the latter state he became a naturalized American citizen. He received a Doctor of Divinity's degree from Rochester University, and was for two years President of Berea College in Kentucky, the only college south of the Mason-Dixon line where negroes were admitted as well as whites. His influence on his son has been incalculable. The Reverend William Boyd Stewart was a most learned man. It was from him that Mr. Stewart got his life long intellectual interests, his intellectual curiosity, and his love for languages and the history of languages. He started the boy in German at the age of five, and Latin at the age of ten. His intellectual curiosity never ceased. At the age of seventy, while Professor Stewart was being stimulated by Nietzsche's writings, the father read Nietzsche again in the original German, so. that up to the end he continued to share his son's interests. He died, full of years, in 1912.

W. K. Stewart spent his early childhood, that is up to the age of five, in Hamilton, Ontario, and then for a few years lived in California and Tennessee, but his adolescent years from ten to seventeen were spent in Kentucky where he attended grammar and high school. At the age of eighteen he entered the University of Toronto, and majored in modern languages and history, with an extra major in philosophy. He has told me that he had no outstanding instructors there who influenced him but that his intellectual development was helped by wide reading. He was a member of Delta Upsilon. It was at Toronto University that he met his future wife, a classmate, Ethel Scott, who was also majoring in modern languages. After he received his A.B. degree in 1897 he left for Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was at Harvard for two years, and in 1898 he received an M.A. in Germanic languages. He spent the following year at Harvard as assistant in German (no teaching), and in further study. Harvard at this time was, academically speaking, near its peak. Charles W. Eliot was President, and William James, Josiah Royce, and George Santayana were the stars of the Philosophy Department. Mr. Stewart heard the lectures of these men, but never matriculated in their courses. He did study old English with Professor Kittridge, the history of German literature with Kuno Francke, and he had the eminent von Jagemann in German philology. It was here also under Dr. Schofield that Professor Stewart studied Scandinavian, a fact not widely known because at Dartmouth there has never been any opportunity to teach the Scandinavian languages. Ibsen and Bjornson were his favorites at this time and he read all their works in the original.

A LIFE OF LEARNING

Before turning to his academic life at Dartmouth I wish to summarize further "the education of William K. Stewart," for like Henry Adams he never has ceased to study or to learn. He went abroad for the first time (studying in Leipzig), with Judge Nelson P. Brown '99, in 1901. Judge Brown was at that time Instructor in English at Dartmouth. I have heard only the merest echoes of this trip but enough for me to realize that they had plenty of fun. Who can ever forget the first impact of Europe on a young and curious mind? In 1904-05 Professor Stewart studied for two semesters at the University of Berlin, and again in the winter of 1912-13, while the spring of 1913 was spent at the Sorbonne. While in Germany he began the foundation of his wide knowledge and love for German music. His favorites then, as now, were Ludwig Beethoven and Richard Wagner. This was the Pre-War Germany, the Germany of Strauss and "The Blue Danube," of the goose stepping Prussian Guard led by the Kaiser down the Sieges Allee with his six sons, of boating on the Wannsee, of unexcelled beer and Wiener-schnitzel, of afternoon tea at the Tiergarten; in short a world which in Germany has gone for good. This was a world still vibrant with memories of Lessing, Goethe, Schiller, Herder, Kleist, Hegel, Kant, Grillparzer, Hebbel, and Heine (now the Dichter unbekannt). Where are they now?

TEACHER AND TRAVELER

Paris was even more romantic in the early days when Mr. Stewart attended the Sorbonne and roamed her tortuous streets on the East Bank. The Dreyfus affair was still in the air, and Zola had but shortly died. The star of Anatole France was safe in the heavens. Bergson was still to publish his Creative Evolution. Bombing planes were not even a dream.

In all Professor Stewart has made fifteen trips to Europe, most of them accompanied by his wife, with stays ranging from three months to a year at a time. He has been as far East as Turkey; he knows the hills of Athens, and the misty, golden coast of Northern Africa. He did not go abroad in the War and Reconstruction years from 1913 to 1921. He has travelled to the West Indies and over these United States and Canada, and all observed and taken in has been grist for his mill. With an eager and alert mind for beauty, for all the many nuances of thought and ideas, for a keen historical sense of the past, he has made the most of his opportunities. He knows Europe as few people know even their own states. Most unobtrusively he has made it his own. All these years he has read many books: the classics, modern literatures in several languages (he is fluent in French, German, Italian, Spanish and the Scandinavian languages), and timely and current books on the problems of our time. The famous British Museum Reading Room has been his sanctuary for many months at a time. Few men that I know have had as steadfast an interest in the drama and he knows it from Calderon to Ibsen, from Hebbel to Bernard Shaw. It was once said of the late Havelock Ellis that he was one of the most civilized men of his time. I should, without hesitation, put W. K. Stewart in this class. And such men are rarer than one generally thinks. Rare indeed.

In 1899 Mr. Stewart became an instructor in German at Dartmouth College and by 1913 was a full professor. His academic career at Dartmouth may be divided into halves: first in the department of German, second, in Comparative Literature. It is not to underestimate his talent as a teacher of German language and literature that I say he reached his full stature as a teacher in Comparative Literature. As early as 1908-1909 he gave a course on "The Romantic Movement," and in the following year one on "Fiction in the Nineteenth Century," but it was not until 1919 that he devoted most of his energy and thought to Comparative Literature though for a year or two thereafter he still gave courses in French and German.

Whatever the department of Comparative Literature may be to-day in the lives of Dartmouth undergraduates, two things may safely be said concerning it. First, that it is, so far as Dartmouth is concerned, Professor Stewart's personal creation which he built up with such conspicuous success and with great foresight (it anticipated many courses later given in other departments) in the twenties. Secondly, (and I am writing now as one of his early students), I can state quite candidly that Mr. Stewart was the first instructor I ever had who aroused my intellectual curiosity, who gave me a far wider background, and who fired in me a dormant love for learning and for truth. In his classes I listened to masterful expositions of the ideas, thought, and influence, of such wide and diverse thinkers as Plato, Aristotle, Aquinas, Dante, Machiavelli, Locke, Mill, Spencer, Rabelais, Descartes, Rousseau, Bergson, Erasmus, Kant, Marx, Hegel, Emerson, Whitman, James, Keats, Wordsworth, and many, many more. Was all knowledge our province in those days? It would almost seem so, but in reality there was too much of an atmosphere of genuine intellectual humility in the instructor. Hearing Mr. Stewart lecture, I am sure we all realized how little we knew, and how short the time left in life to know more. Each lecture left us thinking. Of Professor Stewart's personal views most of us were never sure. We must think forourselves. The rocky road to knowledge could not be made easy even by a great teacher. Also an easy and comfortable faith was no longer possible. Eclecticism flourished and gradually for most of us a personal philosophy emerged. It may have been composed of parts of Plato, surely some of Spinoza, a touch of Voltaire's scepticism, a new meaning in science and scientific thinking from August Comte (who can forget the first thrill of the law of the three stages?) and Darwin, a touch of the naturalism of Lucretius and Santayana, Mill's love for liberty, Wordsworth's feeling for nature, a dram or so of Nietzsche's iron tonic, and a touch here and there of Renan, Thoreau, and Whitman, and perhaps a spot or two of Schopenhauer. For each student there would be a different recipe. But in any case most of us began to think for perhaps the first time in our lives. And thinking under the guidance of Professor Stewart brought us all a little closer to the Renaissance ideal of the well rounded gentleman and scholar. Have we forgotten? Each must answer for himself.

MR. STEWART'S PUPILS

And who were some of these students? I can name only a few owing to lack of space. Here are some connected with the College: Leland Griggs '02, Zoology; Eric P. Kelly '06, English; William H. Murray '02, Tuck School; Harold G. Rugg '06, Assistant Librarian; E. B. Hartshorn '12, Chemistry; Robert O. Conant '13, Registrar; Charles L. Stone '17, Psychology; Harold J. Tobin '17, Political Science; Edmund H. Booth '18, English; G. L. Frost, John Ilurd Jr., Franklin McDuffee, all of the class of 1921, and all members of the English Department; Robert C. Strong '24, Dean of Freshmen; H. Pennington Haile '24, Philosophy; Robert A. McKennan '25,' Sociology; Alexander Laing '25, author and Assistant Librarian; Hugh S. Morrison '26, Art; and Albert W. Levi Jr. '32, Philosophy.

Other educators include Joseph H. Brewer '20, President of Olivet College; W. H. Cowley '24, President of Hamilton College; Paul Bowerman '20 (California); Charles A. Knudson '24' (Michigan); Robert W. Elsasser '21 (Tulane); A. H. Cantril Jr. '28 (Princeton); and many others.

One can not omit Thomas W. Streeter '04, H. R. Lane '07, Wilder Lewis Parkhurst '07, Dr. Thayer A. Smith '10, Dr. Bradley M. Patten '11, J. Theodore Marriner '14, later murdered while on Government Service in Syria, Charles E. Griffith '15, Walter Wanger '15, Douglas VanderHooff 'Ol, Clarke W. Tobin '10, Nathan K. Parker '26, Howland H. Sargeant '32, Richard G. Eberhart '26, Bremer W. Pond '07, Archie B. Gile '17, Ellis O. Briggs '21, Benjamin Tenney Jr. '21, Bill Cunningham '19, Francis H. Horan '22, Clifford B. Orr '22, James M. Reid Jr. '24, Robert M. Morgan '24, John P. Carleton '22, Dr. Simeon T. Cantril '29, Richard H. Mandel '26, William G. Swartchild '30, Robert A. Rolfe '31; and many, many others.

Just what subtle influence Professor Stewart had on these men only they can testify, and such an influence I freely admit is a difficult thing to put into words.

On June 18, 1903, Mr. Stewart married Ethel Scott in Brampton, Ontario. His father performed the marriage ceremony. In those days, as Mrs. Stewart recently told me, couples often had long engagements and waited until a sufficient financial status had been achieved. For many years thousands of students have shared their hospitality, and still do so when they revisit Hanover. Tea on Sunday afternoon used to be a ceremonial occasion throughout the College Year. In recent years, however, so has the College grown that the custom has unfortunately fallen off, but the latchstring at I Occom Ridge has never been withdrawn.

Professor Stewart finds the modern student more sophisticated, but no more intellectually curious or alert than in the past. In 1921-1922 he noticed a distinct change for the better after the broken up years of the War. (My own classmates used to flatter themselves on their brilliance.) His most interesting classes he thinks he had during the year 1919-1920. He does not regret the growth of Dartmouth so long as it remains around two thousand. Having served under three Presidents, William Jewett Tucker, Ernest Fox Nichols, and Ernest Martin Hopkins he remains, as he has always been, loyal to the College. The faculty he says has changed only in size but he thinks the average in teaching is higher than in the old days as men to-day are more thoroughly equipped, and so do a better job.

PROTAGONIST OF J. S. MILL

It is most difficult, and perhaps vain, to attempt an analysis of Professor Stewart's point of view, that is to say, the way in which he regards the curious spectacle of life. He has been designated as "an old fashioned liberal," but to be more precise I should call him an independent in politics, slightly sceptical in turn of mind, but with a sound religious faith. His belief in the English tradition of liberty, as expressed by John Stuart Mill in his famous essay under that title, is one of the profoundest things in his nature. Wordsworth has been an abiding influence. When J. S. Mill was forced by an inner necessity to give up the orthodox religion in which he had been reared, he found in Wordsworth's poetic pantheism an abiding faith. Something similar, I believe, happened to Professor Stewart. Francis Bacon's inductive method of reasoning also played its part in his development, for he early learned that it is only by the inductive method that one may learn new truths. As a youngster, he tells me, he passed through a phase of Shelley worship (the young idealist); but subsequently his thought has been molded on the sterner anvils of Plato, who he reports is pleasant to read; on Spinoza, a noble character whose life was lived on a plane of high thinking and plain living; on Kant, as the source of modern philosophy, and because of his exposition of the categories of the mind in his Critique of Pure Reason, on Hume, in his scepticism and his theory of the association of ideas; on Voltaire for his hatred of superstition and cruelty of man to man; and on Montaigne in his belief in Reason and in his tolerance.

Of the three great questions in philosophy, that is, the existence of God, the question of Free Will, and Immortality, Mr. Stewart's ideas are similar to those of many modern men. His conception of God might be rather vaguely labelled Pantheistic, in the Spinozan sense that we should have an intellectual love of God, but that we should not expect God to love us in return. God is infinite and free because 01 his own nature. God is Nature: the Universe itself considered sub specie aeternitatis. Mr. Stewart believes in Free Will, but regards the dilemma between Determinism and Free Will as insoluble. However, he does not say dogmatically as did Samuel Johnson that "we know the will is free and that's an end to it." He simply believes that a belief in Free Will is essential to a purposive life. He does not regard the question of Personal Immortality as a vital one. It may then be seen that Professor Stewart's philosophical viewpoint is that of a man of his time. He has sloughed off the hell and fire orthodoxy taught in his youth (his own father was a liberal in theology), and he has emerged with a simple faith that nowhere strains credulity, and which, at least for himself, is spiritually satisfying. He believes in Man rather than in Nature (the visible world), and is thus with the Classical-Christian tradition on the Humanistic side.

PHILOSOPHY, HISTORY, BASEBALL, DOGS

What have been his main intellectual hobbies? For many years his mind played over the mystery of the Paradox, both as a vehicle of thought, and as a literary form. His researches here were published some years ago in the Hibbert Journal, probably the most eminent magazine existent on religion and philosophy, and in other publications. Languages, both ancient and modern, have always interested him, and although he was trained in philology, he has had no call to use it in an undergraduate college. History ranks large in his interests and in his intellectual background. So, too, philosophy. He has read exhaustively in world literatures (and he edited recently a large text Adventuresin World Literature, published by Harcourt, Brace & Co.), and he has specialized in the Romantic literatures of England, France, Germany, Russia, Spain, Italy, and the United States. He has edited German texts, and a few years ago produced with his usual nonchalance and modesty, as if it had been but a day's work, the best single essay on the philosophy of Oswald Spengler that I have ever read. He believes that thinking is worth while for itself whether or not it may grind any personal axe.

He is still an ardent baseball fan (he played it when he was young); he loves swimming, and in the old days played a little tennis. He is known widely as a dog lover, and for four decades the Stewart dogs have been known to many generations of students.

I conclude with a brief personal note. The two greatest teachers I have ever had were W. K. Stewart of Dartmouth, and Irving Babbitt of Harvard. One gave me a background, the other moulded, and corrected, an incipient point of view. Both men I am very sure have had, Babbitt the greater for he taught for many years in America's greatest graduate university, an incalculable influence in American education through the teachers they have helped to train. Both were scholars and gentlemen. I give them both my unstinted homage.

NOTHING IS MORE pleasing to an alumnus of any college than an honor which comes from his own Alma Mater. So when Dr. E. H. Carleton of the Eye Institute of the Dartmouth Medical School went over to Brunswick, Maine, last June, to receive the degree of Doctor of Science, he had reason to rejoice for an honor well merited "in his own country." President Sills of Bowdoin commented on the Doctor's work in "the now widely known Dartmouth Eye Clinic"—his tremendous courage and grit in operating with his left hand, and his rise to the post of clinical specialist. But President Sills also referred playfully, as those who confer honorary degrees are likely to refer to some quality other than that of personality and work, to the doctor as"one of Bowdoin's immortal athletes of the gay nineties." There's a legend among his mates that he also played football for Dartmouth somewhere in the period 1896-98 but it isn't in the records.

An enthusiastic student of American Literature, John Wallace Finch, a Wesleyan alumnus, has come to Dartmouth after five years' work at Harvard. Besides former articles in the New Republic and Sewanee Review, Mr. Finch is publishing in the December number of the New England Quarterly an article entitled "The New England Prodigal" (E. E. Cummings). Working on a thesis, "Hawthorne and Henry James" the new instructor is a candidate for a degree at Harvard which has as yet not been conferred upon anyone, the degree of Ph.D. in American Civilization. A major in English in Wesleyan, graduating with highest honors, and recipient of the Harvard Monthly Magazine prize at Harvard, he has been continuously at work in American Literature field since 1933.

Whether or not it suggests any trend in modern education, the fact remains that Charles Johnstone Armstrong who comes to the Department of Classics this year as an instructor finds a class of 10 men beginning a study of the Greek language. With classics de-emphasized generally for many years in American colleges, this number in a class actually beginning the study of Greek, is a bit unusual. He carries also work in three other courses, including classical civilization. Mr. Armstrong who was graduated from University of British Columbia with first honors in classics, continued his work at Harvard, where in the years 1933-35 he was a University Fellow. He held the Watson Goodwin fellowship in '35-'36. He came to Dartmouth from Rollins College where he was assistant professor of Classics. At present he is working on a new translation of Suetonius' Lives ofTwelve Caesars. In many ways Mr. Armstrong is particularly suited to the life of a college campus, with interest in many activities, as his record shows. As an undergraduate he was president of the student council, a member of the University's Musical Society, and even took part in the production of a Gilbert and Sullivan opera. He worked with the chapel choir at Rollins and with the Bach Festival of Winter Park, 1937-38.

It wasn't so long ago, as most alumni can remember, that every professor on the Dartmouth campus had his nickname. Perhaps this custom still exists, indeed it does in the case of a few teachers or officers of administration, but one doesn't hear about the campus talk of "Chuck" or "Tattledo" (a professor who won his nickname by his rapid pronunciation of "That'll do" after each recitation) or "Type" or "Johnny K" or anything of that kind. But it was once necessary to establish a good nickname for a new instructor before he was in Hanover very long. When the late Professor Colby first came to Dartmouth, after a sojourn in more fashionable environs, it is told, members of his family were a little distressed lest he fall into slack ways of dressing, said to be common in Hanover. So the man who was to become one of Dartmouth's most noted figures, hied him straightway to New York and purchased six of the most fashionable suits of clothes that money could buy. With these he flashed upon the Hanover scene. A few months after his arrival, one member of the department in which he worked, inquired of another member "how was that young dude getting along?" Some students happened to overhear the remark, and from that day forward Professor Colby was "Dude" Colby, and he took great pleasure in the name.

That England and Germany may find themselves united against Soviet Russia, when the din of the present strife has died away and the Nazi menace removed, is an opinion put forth by Professor Rees Higgs Bowen of the Department of Sociology, one of Dartmouth's widest travelers and most extensive readers. German and English interests are fundamentally similar, he says, and both are antagonistic to the ideals and aims of Soviet Russia. Russian youth has been raised, he is quoted as saying, in an aggressive and intolerant manner. The workers have as a whole very low wages except for the top technicians. Professor Bowen is a native of England, and a graduate of Oxford.

The country has recently become Aniseikonian conscious, not only through an article in Cosmopolitan but through pamphlets to school teachers. In short Aniseikonia is a newly discovered eye condition in which the images formed in the two eyes are unequal in size and shape. In the treatment of this condition, the Eye Clinic at Dartmouth is immensely interested. Down in Texas a school teacher believes that arranging school children in a circle about a chart or a map has a tendency to develop this condition, and as a remedy suggests straight rows of chairs or double straight rows. When Professors Gordon H. Gliddon and Kenneth N. Ogle went recently to a meeting of the Optical Society of America, at Lake Placid, the former broke up discussions on other subjects by setting up a model of a grotesquely warped room, and then had delegates look through a pair of specially constructed glasses which brought the vision to normal. As the report of the meeting stated "everybody had to look."

DR. EI.MER H. CARLETON Dartmouth Medical School graduate 1897,alumnus of Bowdoin College, and honoredby Bowdoin with the degree of D.Sc.

THIS IS THE THIRD of a series of biographical sketches published monthly during the year, describingthe lives of members of the facultynow at the height of their careersand influence in the College.

NEWS OF THEFACULTY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsBig Little Green Team

December 1939 By BILL CUNNINGHAM '19 -

Article

ArticleA Landmark Is Gone

December 1939 By WILLIAM A. ROBINSON, Robert Lincoln O'brien '91 -

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

December 1939 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931*

December 1939 By CHARLES S. MCALLISTER, CRAIG THORNE JR. -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

December 1939 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929*

December 1939 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, WILLIAM O. KEYES

ERIC P. KELLY '06

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS TO THE EDITOR

January 1936 -

Article

ArticleSquash Little '91 "Constant Champion"

October 1936 By ERIC P. KELLY '06 -

Books

BooksTHE NEW YORK TRIBUNE SINCE THE CIVIL WAR

February 1937 By Eric P. Kelly '06 -

Article

ArticleExacting Requirements in Science

January 1940 By ERIC P. KELLY '06 -

Article

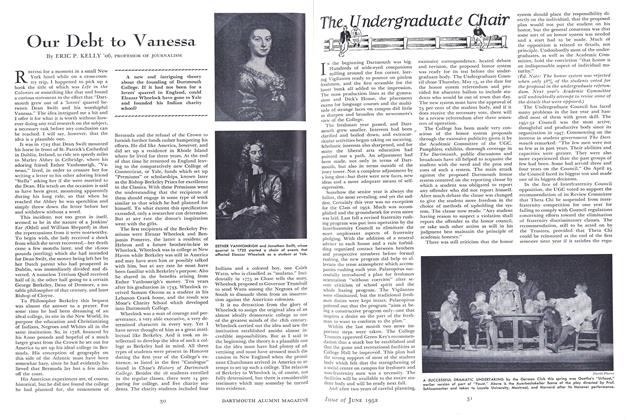

ArticleOur Debt to Vanessa

June 1952 By ERIC P. KELLY '06 -

Books

BooksTHE STOLEN SPRUCE.

October 1952 By Eric P. Kelly '06

HERBERT F. WEST '22

-

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

February 1938 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

February 1940 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

December 1942 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksAMERICAN LITERATURE FOR COLLEGES.

May 1954 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

April 1955 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksTHE IVY LEAGUE TODAY.

December 1961 By HERBERT F. WEST '22