THE TEACHER of many courses in the social sciences has an exceedingly difficult task. He is, in the first place, not teaching an exact science. On many of the questions discussed in classrooms the correct answer lies in the future—it is not carried in any textbook nor can the accuracy of a formula always be demonstrated from experience of the past. Problems of government, and the economy and society of the country and the world, are changing. To arouse and stimulate his students to serious and thoughtful consideration of these questions is the exacting task of the conscientious teacher without himself showing a strong personal bias.

In his article in this issue Mr. Elsbree speaks from years of experience with undergraduates at Dartmouth and Harvard. He has found it difficult to open the minds of his students. He now breaks into the circle described above, where students, teachers, and parents all find failings in each other, by calling on the elders to accept the responsibility of setting an example of tolerance for their sons. He implies, and the reader may fairly infer from his discussion, that a youth of 17, 18, or 19 comes to the college process too late for his mind to be aroused to analytical and vigorous thought.

It is our opinion, to the contrary, that far from being too late to work with its student material, the college is successful in its purposes if any considerable number of men become thoroughly aroused before graduation. At least one of the aims of the liberal college is to develop maturity and perspective in its undergraduates. The cumulative effect of college is sometimes not fully realized until after graduation when later experiences clarify the goals of mental growth toward which the college strives to guide its students.

The home environment and other eatly influences are all-important in determming the attitudes of a college student Noblesse oblige is not the only mark of quality that a man either has or does not have before he packs his trunk and heads for college. If not too late, it is very late, to change these emotional attitudes in the four years of college. But the major point of discussion is the question of intellectual responsibility—not values, important as they are. It is the opportunity and the job of the college to provide the stimulus for intellectual growth and greater maturity, without bias or prejudice. This is also the duty of parents, whose open-minded attitudes are bound to be reflected in their sons.

In our opinion the undergraduate body, selectively admitted from three times as many applicants, has potentialities far from developed in many cases at the end of senior year. This must also be the opinion of Mr. Elsbree and many other teachers. If the material of high calibre is present, and results are not satisfactory, should not the whole educational process be scrutinized as well as the attitudes of fathers and youth?

Comments from parents and alumni will be welcomed in these columns. Their first hand experience with the product of Dartmouth, in the years after college when results can only fairly be measured, would be valued in the discussion thoughtfully raised by Mr. Elsbree.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

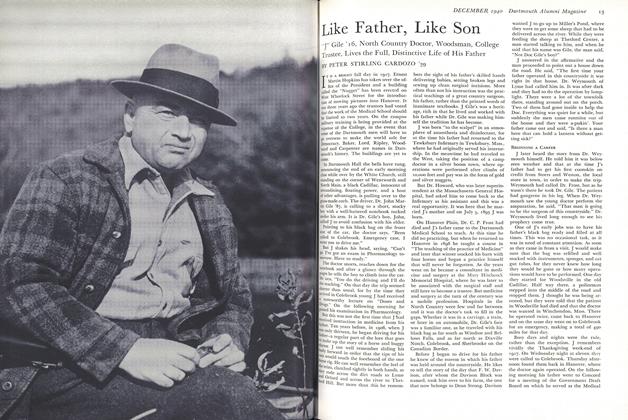

ArticleLike Father, Like Son

December 1940 By PETER STIRLING CARDOZO '39 -

Article

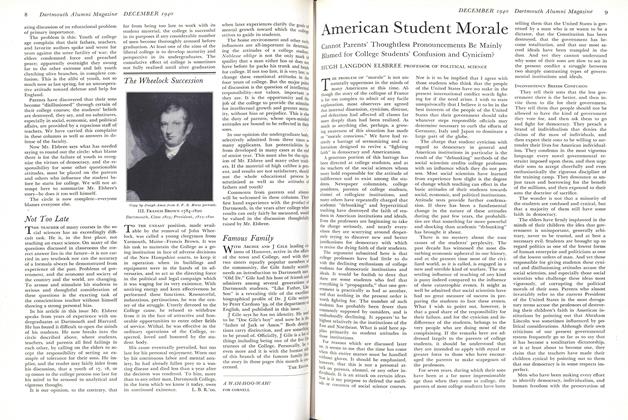

ArticleAmerican Student Morale

December 1940 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1940 By Charles Bolte '41 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917*

December 1940 By EUGENE D. TOWLER, DONALD BROOKS -

Article

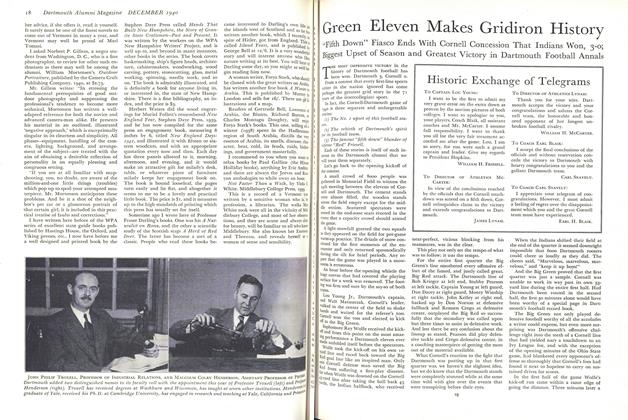

ArticleGreen Eleven Makes Gridiron History

December 1940 -

Class Notes

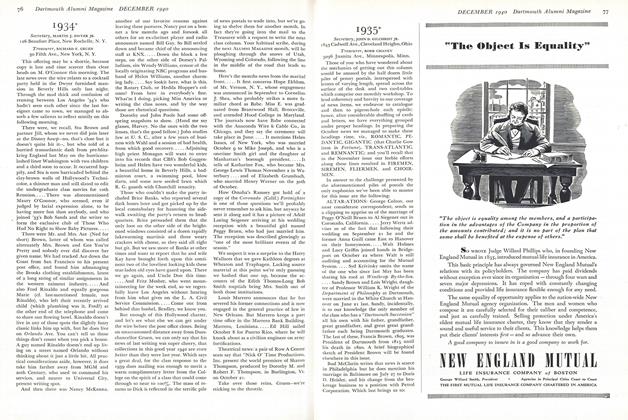

Class Notes1935*

December 1940 By JOHN D. GILCHRIST JR., BOBB CHANEY

The Editor.

-

Article

ArticleGradus Ad Parnassum

March 1939 By The Editor. -

Article

ArticleWho Alibis Whom ?

December 1940 By The Editor. -

Article

ArticleNot Convicted

January 1941 By The Editor. -

Article

ArticleCensors of the Schools

January 1941 By The Editor. -

Article

ArticleTolerance

January 1941 By The Editor. -

Article

ArticleAmerican Republics

January 1941 By The Editor.