Orchids to Fund Workers

To THE EDITOR: The other day I received a most courteous and exceptionally pleasing letter from Sumner Emerson, Chairman of the Alumni Fund, advising that I—along with many others—had been elected a "Dartmouth Regular" in recognition of a certain amount of consistency in contributing to the Fund.

While such recognition is perhaps deserved (though to me, giving to the Fund is a privilege, and not a duty) it occurs to me how much more deserving of the recognition and gratitude of every Dartmouth man, are those who have been in charge of running the Fund and making the collections.

A glimpse at the report in the last issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE will show anyone who is sufficiently interested to make even the most casual study of it, what a truly remarkable job the Executive Committee and class agents have done. In spite of the 10-years-depression and terrible conditions, they have carried on and accomplished an almost unbelievable job.

If anyone deserves credit, it is these men, and I for one would like to see some fitting recognition given them. Whether it be by each class to its own class agent or by the general committee or by the officers of the college, I think that some proper action should be taken and would like to suggest that you "sound out" some of the Alumni and start some such action.

Every one connected with the running of the Fund campaign has done a swell job and one of great value to the College and is deserving of suitable recognition on the part of the College and all Dartmouth men.

Cleveland, Ohio

Teach Students to Think

To THE EDITOR: Your publication of the recent controversy over Mr. Qua's letter is commendable. An alumni magazine should do more than just report news of the college. It should encourage an occasional bit of thinking on the part of the alumni as to the role of the college.

I find myself in complete sympathy with the tone of Mr. Kirkland's letter, but the letter from Ben Ames Williams was a trifle disturbing. Mr. Williams apparently feels that the students' minds should be nurtured on literature that is not disturbing or upsetting to their equanimity. He might recommend the Saturday Evening Post instead of Karl Marx's Communist Manifesto. But why have a college if the students fail to think about the problems of society?

The present turmoil of the twentieth century world has been likened to the great upheavals that took place in the Age of the Reformation. In a world that is changing its concept of values and acquiring new standards, it is the duty of a professor to try to explain this and help the student seek new values. Teaching that mentions value concepts and ways of life is disturbing to the status quo at any time. The conservative will always resist and fight change. But there can be no intelligent solution for the problems of the world today unless the students are taught to think. After their student careers they will go out into the world of business or the professions, and unless they have been taught to think in college they will not think very clearly as members of adult society.

Mr. Williams feels that modern education is too intensive for the student. It causes nervous breakdowns. I doubt that this is a just criticism of the Dartmouth atmosphere. The four years spent at college are less difficult than what usually follows. If a man is not prepared to accept his responsibilities in the years when he is a fine physical specimen, how will he later on?

The University of Chicago.

Facts Without Theory?

To THE EDITOR: The letter by Ben Ames Williams, president of the General Association of Alumni, makes the issue raised by Francis Qua still more serious. Williams describes "the proper function of the college" in an utterly inadequate way because he demands no real intellectual or emotional awakening. He would have the college "lead youngsters to appreciate the good things in life—music, literature, art, sculpture, etc.—so as to create in each one of them a reservoir of happiness upon which they can draw at will." But does he wish the arts to sensitize them to the terrors, ecstasies, ironies, and absurdities of life? He would have the college develop "a disciplined mind, capable of being used as an efficient tool." But is the mind only a tool for earning a living or getting ahead of competitors? Should not the student be stirred to the recognition that nature and society are full of problems which have not been solved by ancient theologians, contemporary scientists, or contemporary politicians, but which challenge the utmost intellectual efforts of oncoming generations?

He would have the College offer to its students "a smattering of the more interesting facts (not theories!) about the world in which they live and the people who share the world with them." Does he suppose that facts can be separated from theories? Would he offer biology without evolution? Can any one read the headlines about such facts as unemployment and war, Hitler and Stalin, without wondering how they got that way? In wondering one forms theories. Unemployment, one guesses, is due to the employment of married women, or to new machines, or to laziness. Hitler and Stalin, one guesses, make war because they are bad men; if they had gone to church oftener in their childhood, the world would now be at peace—or wouldn't it? Facts suggest theories—usually silly ones, and the only remedy for silly theories is wiser theories.

Williams fears "a sort of mental indigestion produced by trying to digest theories." It is true that an intellectual awakening is often painful. It is pleasanter to assume, if one can, that the preacher in Podunk, or the Chamber of Commerce of Zenith City, has all the answers. But it seems to me that the facts of 1940 are more indigestible than any theories, and that only theories can help us to digest them. The effort to form theories about them gives at least some hope of finding that some causes of present evils are discoverable and removable.

Contact with controversial theories cannot be delayed until intellectual maturity is achieved, any more than contact with danger can be delayed until courage is achieved. The intellectual beginner may blunder, or form persistent bad habits, or become discouraged, like the beginner at swimming or golf; but this is no reason for not beginning.

The college age is the best age in which to tackle controversial theories. Before that, experience is too limited and parental pressure is too strong. After that, the pressures of employer, family, lodge, and business or professional clubs too often stifle any freedom of thought. But in college, the student's mind is relatively free, and he is in contact with scholars whose outlook is less biased, and whose methods are more scientific, than those of any group he is likely to meet.

Let us not demand that the college turn out efficient, contented slaves of their employers and of Mrs. Grundy, who can palliate their boredom with the more innocuous forms of literature. Let us hope, instead, that many of our graduates will have become alert to the tragic problems of life. Let us hope that they will help to form a more enlightened and rationally progressive public opinion. Let us hope that at least a few will become pioneers in scientific research or philosophic interpretation, leaders in social reform, or martyrs if need be in the perennial battle for human rights.

Ohio Stale University,Columbus, Ohio.[This is the last of the Qua correspondence.—ED.]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

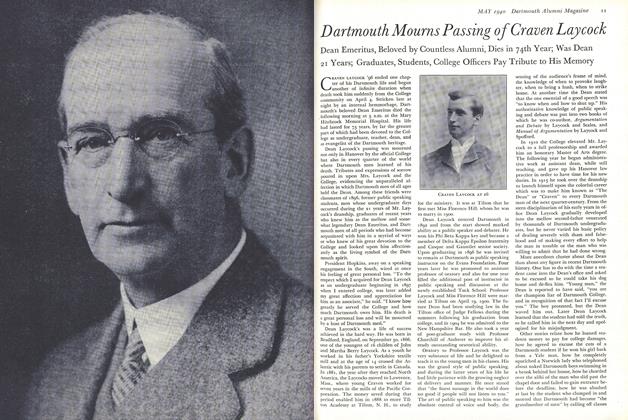

ArticleDartmouth Mourns Passing of Craven Lay cock

May 1940 -

Article

ArticleI Found Seven Latinos

May 1940 -

Article

ArticleJohn M. Mecklin, Teacher

May 1940 By Thomas W. Braden '40 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915*

May 1940 By CHARLES R. TAPLIN, RUSSELL B. LIVERMORE -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

May 1940 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

May 1940 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, H. WARREN WILSON

Letters to the Editor

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorALUMNI OPINION

January, 1911 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorThe Dana Family

March 1936 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

December 1938 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS TO THE EDITOR

OCTOBER 1963 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

DECEMBER 1981 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

September 1986