An Undergraduate Interviews Latin America in Hanover Discovering Different Opinions, Beliefs, Objectives

No DOUBT ALL OF us have come in contact with them at sometime or other We must have seen them walking down Main Street at late hours of the night while they talked a strange, incomprehensible language of jumping phrases and rhythmic sounds. Once or twice we must have observed them grouped closely together in a booth at the Wigwam or the Paddock, sipping a beer, and still arguing with vociferous words and violent motions. To the more naive of us, they seem like the strange characters of a foreign novel who have suddenly and mysteriously landed in Hanover. But to those who have taken Spanish i, or who happen to be acquainted with the group, these individuals drop all the glamour and mystery that seemingly separates them from the rest of us. The jibbering, excited personages become merely the few Latin Americans enrolled at Dartmouth College.

And so we see them every day They have become familiar. Some of us "rugged individualists" have baptized them "spicks" or "greaseballs." To the more idealistic and patriotic, they are the "Good Neighbors" that FDR talks about. And to others they represent merely a group of "whacks." We live with them, but never wonder why there seems to exist a barrier between them and us. Perhaps some of us, moved by transcendental curiosity, have tried to penetrate that barrier. Perhaps we have wanted to know why they live and how they live in this little world that we know as Dartmouth. Perhaps we have gone to them, and talked And perhaps we have understood

My own curiosity led me into one of the greatest adventures of my college careerthe discovery of seven personalities—seven different, individualistic worlds—that live among us. I decided to cross the barrier, to try and penetrate these worlds, and to find their impressions of college life. What do they think of all this?—the snow, the profs, Eleazar—in other words, what do they think of Dartmouth? Do they live our vulgar, everyday existence, or do they exist in a world of memories of torrid climates and romantic escapades? Can they accept the educational policies of the College? What are their future plans? And how about the American girls, and those famed senoritas of passionate eyes?—a type implanted in our minds through a few movies.

And so I wandered into these strange worlds, and found that the seven men are not strange at all. They are just as human as we are, just as hopeful, just as enthusiastic about Dartmouth. Perhaps one or two have ideas which could be considered "radical" in certain American quarters.

.... But they certainly are not so tremen-dously distant from the rest of us. One thing seems to bother most of them: the coldness of Hanover, one factor which perhaps keeps down the enrollment of Latin American students. They all seem to like the same things: rumbas, liberal houseparties, sports, the spirit of Dartmouth.

.... They are all proud of the same thing: their Spanish race Yet, there is a cer- tain individuality present in each of the seven. There is a bit of the native land in every one of their hearts. That is why to meet them is an experience for anyone who can classify himself as an "average American." .... And so I decided to interview them

Frank Lallande is a freshman from San- turce, a nice residential section near San Juan, Puerto Rico. He has a youthful, dis- arming smile that makes it easy for him to get along with Americans He has traveled in California and the South, but New England is a new experience for him. So far he likes it, but thinks the weather is a little too cold. He had never seen snow fall until he came here "Except in the cinema," he adds.

Frank talks easily and candidly about the relations between students and professors here at Dartmouth: "You can say anything you please and the prof will discuss it with you. Here there's not that formality between instructors and pupils that I saw back home. But what I like best at Dartmouth is the freedom given to freshmen. If a fellow wants to run around, that's O.K. If he wants to study, that's 0.K., too. Everything is left up to the individual. I also like the system of sports. These Americans always manage to be doing something."

Frank disagrees with most of his countrymen: he thinks Orozco's murals are pretty awful. They mean nothing to him, remind him of Dali. But he doesn't have to look at them. Yet he must write English themes, which he dislikes greatly, and for which he says schools in American possessions do not prepare the student. He wishes Dartmouth wasn't so far from a big city. He finally admits, however, that the proximity of a large metropolis would ruin some of the college "spirit," something new to him, which he already admires.

Roberto Alfonso Herrera '43, is perhaps one of the most interesting of the group. Probably because he arrived in this country for the first time in his life just two weeks before registration. He has studied in Paris and in his native city, Guatemala City, C. A. He is highly refined, and has an artistic, suave temperament. He speaks with the poise and self-assurance of a young cosmopolitan. His words have not lost the snuffling accent of his native tongue.

"My first impressions of this country are deeply written in my mind. American hospitality is grand. Everyone has been very good to me. To live in this country, one must have the help of the neighbor. It isn't as in our countries, where one can be lazy and pessimistic, and live on a few bananas a day Dartmouth fascinates me in many respects. The 'college spirit,' based on the students' honor, is great. What a difference from the University of Guatemala, where the students of the Medical School are bitter rivals of the Engineering School. Spirit is indispensable in any school. In this country students never go on those stupid strikes, so common in our universities."

Roberto so far has been very complimentary to American education and American students. Later I find that he believes many things wrong with both. "Take art," he continues, "I heard that Dartmouth was an art-minded college. No one has followed Orozco's steps. The Eleazar Wheelock murals are much inferior. There is around here a multitude of subjects which could be exploited by a good artist. .... American students don't seem to appreciate classical music. Not that I think 'swing' is not good In its place, of course Many students seem to be far too naive to be in college. Many are innocent in amorous matters to very late ages. Their sense of humor isn't too good, either. They will laugh at anything. I have even noticed this at very serious lectures The professors are excellent, although some stick to one subject too much. There should be more general discussions in class. Philosophizing isn't bad at times, you know "

I feel that Herrera has taken Dartmouth, and has weighed it correctly. A foreigner seems to be able to tell our faults much better than we can. He has done it with? both poise and precision.

Joaquin Vallarino '43, is a son of the torrid Panama City. And the" unbelievable thing is that he came to Dartmouth to see plenty of snow, and even to adventure into a bit of skiing—a sport banned by the rest of his countrymen. Joaquin is very expressive, seemingly agile, and his posture shows that he didn't waste two years at Culver Military. His main problem now is trying to explain to me a great phenomena that has taken place in his life since he came to college

"It's hard to explain," he says. "It's strange, but you'll see what I mean. When I first came here, I felt very much out of place. Now that a few months have gone, I feel perfectly at home. I don't even want to be back in Panama! Such content is funny to explain. It's phenomenal! About college, eh? Well, in the first place, I think there's too much pressure put on the individual in order that he may work. It should be entirely up to the man. College should mean complete freedom in such matters.

.... Dormitory and fraternity plans are excellent. Something we haven't got in our schools. They give the fellows a chance to live together It's almost like a family. .... The Americans are a fine bunch, but they do not seem sincere, or at least expressive. They may be thinking one thing, and doing the opposite. Hell, when I feel like crying, it's a cinch you won't find me laughing! Perhaps that's the Spanish temperament. I'll take it over bad acting any day."

Joaquin has some excellent ideas. His travels in Europe and the United States have given him a certain polish. He says his favorite spot is California, and he may return there soon. He still has to try the Hanover snows! Good skiing, Joaquin!

Jose Lopez-Silvero, a sophomore from Havana, Cuba, is next on my list of visits. He is a good-looking six-footer, made rugged by the winds of Canada, where he spent his preparatory school years. After graduation he plans to enter the University of Havana Law School. According to Joe, culture is not an end in itself, and therefore college doesn't prepare for anything. Real work and specialization begin in graduate schools.

Lopez-Silvero has some definite, wellformed ideas about college life. His Cubah point of view hasn't been changed by years in the North. He expounds his theories with great energy, wishes they'd be published some day "I hate the way some fellows dress around here. What's this, a hobo jungle? Overalls are hardly the thing to wear to classes The bad taste of some Americans is only surpassed by their stupidity! They have complete ignorance of Latin-American subjects, and believe themselves the masters of the Hemisphere. They should be called North Americans, not Americans. What do they think we are? They have no respect for their sister republics. Their superiority complex is entirely unfounded! There should be more college courses to teach the importance of Latin America. More organizations like Ambas Americas' should be encouraged on this campus!!"

Here Joe seems to reach a boiling point, then suddenly changes the subject. "The faith of some of the Catholic students astounds me. It's much stronger than ours.

.... The basis of American college life—of American life—seems to be money, money, and more money! You don't see this in Cuba or in Canada. .... I find that American students have too much sense of responsibility. They think before doing anything, whereas we just do it. That's all!"

Before I leave I must ask Joe about his opinion of American girls. "In general, American girls are all right. Very nice to go around with, because of their liberty. But I'll marry a girl of my nationality, if possible. To them, marriage means more. It's their life!"

I say goodbye to Joe, and think of that last sentence. The words seem to jump and hit me in the eye. "It's their life!"

In 101 Chase lives the dean of the Dartmouth Latin American students, Andres Calleja '39, Thayer second year. Andy has been around for five years and really has absorbed some of the Dartmouth customs. He has just returned from a six month engineering practice in his native Cuba, where he worked as an assistant engineer in the road from Cienfuegos to Topes de Collantes. He says conditions were pretty bad due to the hot climate, but the experience was great.

Andy is jovial, good-humoured, extremely pleasant. His romantic moustache reminds me of some legendary Don. He's seated at his desk, which is covered by a multitude of engineering texts with their mathematical hieroglyphics. I realize Andy is a busy man, and my visit must be short.

"During the last two years I have been too busy at Thayer School to make any worthy observations of the college and its policies. Although I lived off-campus my first two years, I managed to get as much social life as possible, and came to understand most of the student habits. Finally during my junior year I came to believe firmly in the Dartmouth 'Spirit.' It's such an obvious thing that I don't see how anyone can deny its existence It's the basis of student life. In Cuba, where I went to Prep School, I found that a certain spirit did exist in school life, but not nearly so strong as that found here.

"Another thing I admire about American colleges is their liberty. The individual is left alone to develop a character and to form his own ideas. In our countries perhaps the close familiarity between students tends to stereotype some of their ideas-especially their political ideas. I find that American college men live together in great harmony. This isn't true of all the American people. Why, in a big city a family may live next to another for years, and the two will never become even acquainted. This is not true in Cuba, where great familiarity exists in this respect."

"What Cuban custom do you miss the most?" I ask.

"El Relajo It's hard to explain this word. It may be translated as the 'fooling around.' It's the observation of certain romantic and piquant customs which have their origin in the temperament of the Cuban Yet, I manage to get together with some of the other latinos, and we make a big relajo, be it in White River or Lebanon Oh, before you go. I must say that Spanish courses should be emphasized more in American colleges. In our schools back home English is greatly emphasized, for we realize the importance of good inter-American relations "

After that long walk down Tuck Drive, I have to climb four long flights of stairs to the Wheeler Hall "penthouse" which accommodates my last two victims: Luis J.

Zalamea '42, of Bogota, Colombia, S. A., and Jose M. Infante '4.3, of Holguin, Cuba. I have been warned against both of these gentlemen. I hear that they take their ideas pretty seriously, and that some aren't bad at all. That is, if one can understand them.

I find Zalamea at home, but he informs me that his roommate is in class. "The Count," as he is known to his intimates, is cordial enough, although at times his effervescence in talking turns into apparent anger. I can see that all the emotion and pride of his race are packed in him. He's indeed proud of his ancestry, for his most prized possession is an ancient coat of arms of his family, which he proceeds to explain to me in heraldic terms. I simply can't understand a thing.

"So you want to know what I think of Dartmouth? A big order. I have thought it out many times, though Dartmouth to me is a world. The only trouble is that it is a narrow, small world. You talk about Main Street and its Babbitts and Rotarians. This is worse than Main Street, because it's a combination of all the Main Streets in the United States And these sociological backgrounds are the only dictators of the actions of most of the Dartmouth students There's an accepted way of living as a Dartmouth man. It isn't dictated by the administration, or by the faculty. It's dictated by the student body. The Creed of the Dartmouth man is to be sloppy, profane, 'he-mannish,' kiddish, to show respect for nothing, to ski in the winter, and go to Smith in the spring. If you are original enough to go beyond this pattern of living, you are rapidly classified by the rest as a 'wettie,' a 'whack,' or a 'queer'—three words which I hate because they are meaningless. I am considered a 'whack' in certain quarters, and I am very proud of it!

"Dartmouth students could afford to be more intellectual. Especially when they have such great opportunities under their very noses. Baker Library with its unfathomable quantities of books is one source of stimulus for the intellect. Learning can be acquired more directly, merely by talking to different students; by getting the other fellow's point of view. Just like you are doing now. Private conferences and informal discussions with professors have astounding results. But I suppose this would be considered by some as 'apple polishing.' "

"And some of your adventures?" I ask. "Is it true that last year you changed your suit of tails for a guitar in order to serenade some local beauty?"

"I refuse to answer about that guitar. Adventures? Few in the last years. I did a lot of traveling before I came up here, so things seem pretty quiet now. All I do is a little writing, thinking, and reading. If you mean amorous adventures, I have nothing for publication, except this: Spanish girls are the same as Americans to me. If I fall in love with an American, I'm going to marry her. I disagree with my countrymen on this point. I hold no international prejudices in this respect What do I miss most? Oh, I guess I miss the old student reunions in the cafe. I do miss the cafe. I remember how we used to discuss everything from politics to bullfights Oh, yes I also miss a good bullfight And I miss the political movements. You know, in Latin America the students are the leaders of all political movements and idealistic reforms "

At this point Zalamea's conversation is suddenly interrupted when the door opens, and Infante comes in brushing the snow off his coat. "Phewwww, what weather!" is his only greeting. I can see that this son of tropical Cuba isn't quite used to Hanover weather Joe is a fine specimen of Latin grace and vigor: tanned skin, dark, bushy hair, dark brown eyes, well-formed body. His broad shoulders and chest are the products of many years of rowing and playing soccer, Cuba's national sport

When Joe learns the purpose of my visit, he merely remarks, "I bet Zalamea has been doing a lot of talking." Ah, but I want Joe's views, too. If Zalamea tends to be a Machiavelli, Infante certainly tries to be a Confucius

Finally Joe volunteers to express his opinions. He talks slowly, as if trying to measure every phrase, every word

"Whenever people ask me what I think of Dartmouth and how it has affected me, I always try not to be critical, skeptical, or emotional with what I tell them. It's simple: I have no well formed ideas as yet. I cannot be as yet considered as a 'Dartmouth Man'—a term which is widely used, but often misinterpreted It's very hard for a first-year man to have any sound conviction about the College. All those who have gone through this period of college life know that. It's a difficult perioda period when one thinks Dartmouth is one of two things: 'A nice place,' or 'HELL.' We may play with a lot of meaningless and ill-founded phrases, but good opinions cannot be founded so early You go and ask college graduates why they think college was worth while. They will say they found something there. Until I find that something, I will refuse to give opinions on college life here

"To criticize Dartmouth for its lack of women, its drinking, and for other many things necessary to satisfy our bodily appetites, would be superfluous and stupid. We find these things in any college. In any part of the world The same goes for the fellows. They are the same here as in anywhere in the world: some good, some bad, some unimportant. To form the opinion of a man, I don't compare him to my countrymen. I merely analyze him according to my own senses. It would be stupid to impose the standards of another nationality in choosing American friends and acquaintances "

After a pleasant visit, I leave Joe and "The Count." I am sorry I have no more to interview. I have visited seven worlds; have come back with seven different sets of ideals, of hopes, of dreams. I have met optimists and pessimists. Cynics, aesthetes, philosophers, dreamers, jokers All with that temperament which makes them so pleasant With that brilliant temperament of their race So long, amigos. Hasta la vista

[We welcome this description of interviews with the Latinos in Dartmouth.Readers will be interested to learn thatLuis J. Zalamea '42, one of the subjects ofthe interviews, is also the author of the

-ED.]

article.

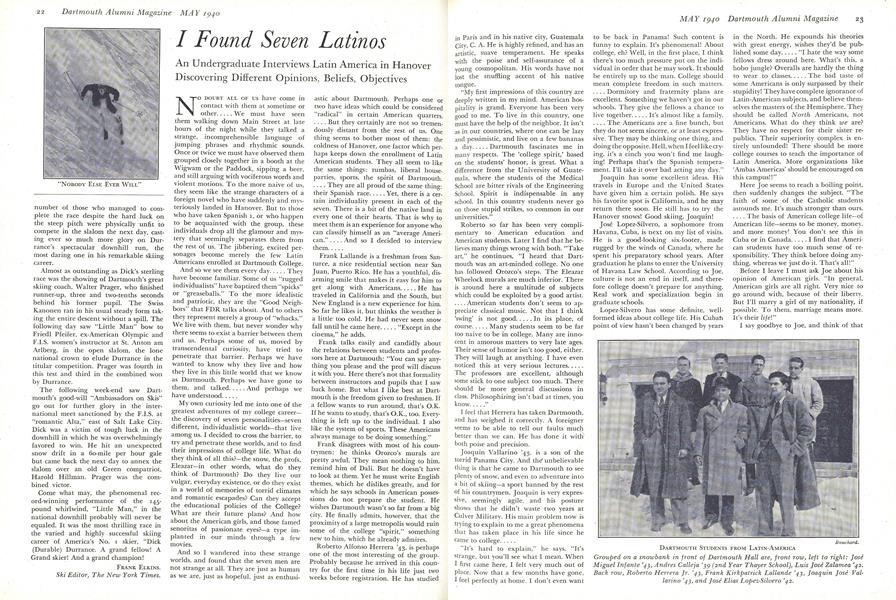

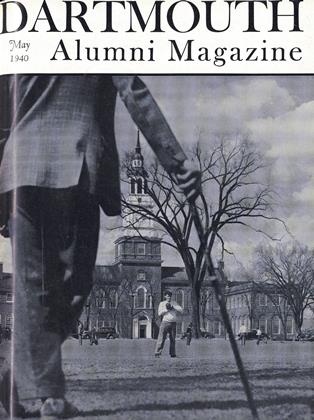

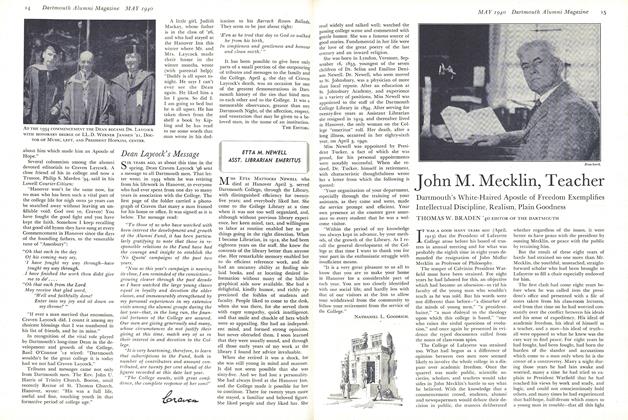

DARTMOUTH STUDENTS FROM LATIN-AMERICA Grouped on a snowbank in front of Dartmouth Hall are, from row, left to right: JoseMiguel Infante '43, Andres Calleja '351 (2nd Year Thayer School), Luis Jose Zalamea '42.Back row, Roberto Herrera Jr. '43, Frank Kirkpatrick Lallande '43, Joaquin Jose Vallarino '43, and Jose Elias Lopez-Silvero '42.

TOWER ROOM Leisurely reading flourishes in this famedsection of Baker Library. Dallin's bronzereplica in miniature of "Appeal to the GreatSpirit" was the gift of Leslie P. Snow 'B6.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

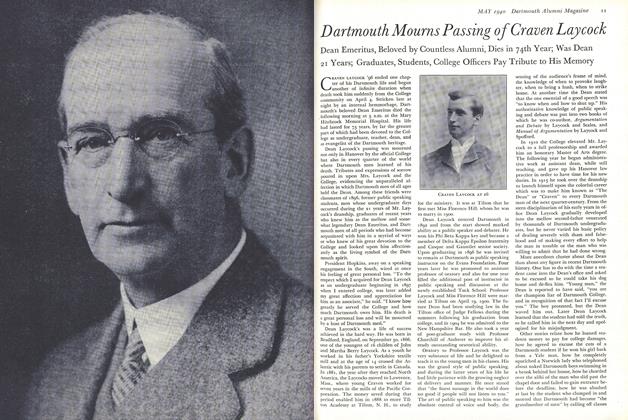

ArticleDartmouth Mourns Passing of Craven Lay cock

May 1940 -

Article

ArticleJohn M. Mecklin, Teacher

May 1940 By Thomas W. Braden '40 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915*

May 1940 By CHARLES R. TAPLIN, RUSSELL B. LIVERMORE -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

May 1940 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

May 1940 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, H. WARREN WILSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935*

May 1940 By GARDNER CUSHMAN, DONALD W. FRASER