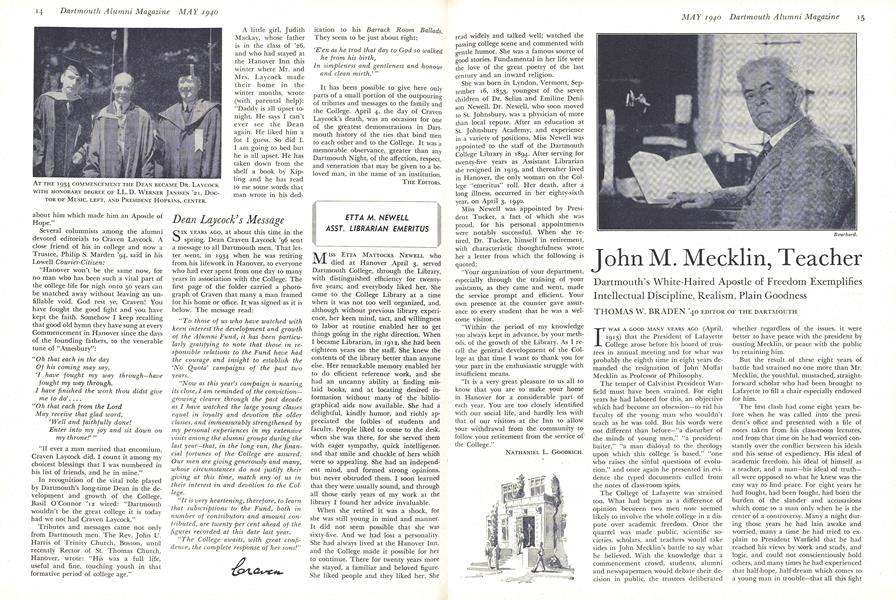

Dartmouth's White-Haired Apostle of Freedom Exemplifies Intellectual Discipline, Realism, Plain Goodness

IT WAS A GOOD MANY YEARS AGO (April, 1913) that the President of Lafayette College arose before his board of trustees in annual meeting and for what was probably the eighth time in eight years demanded the resignation of John Moffat Mecklin as Professor of Philosophy.

The temper of Calvinist President Warfield must have been strained. For eight years he had labored for this, an objective which had become an obsession—to rid his faculty of the young man who wouldn't teach as he was told. But his words were not different than before—"a disturber of the minds of young men," "a presidentbaiter," "a man disloyal to the theology upon which this college is based," "one who raises the sinful questions of evolution," and once again he presented in evidence the typed documents culled from the notes of class-room spies.

The College of Lafayette was strained too. What had begun as a difference of opinion between two men now seemed likely to involve the whole college in a dispute over academic freedom. Once the quarrel was made public, scientific societies, scholars, and teachers would take he believed. With the knowledge that a commencement crowd, students, alumni and newspapermen would debate their decision in public, the -trustees deliberated whether regardless of the issues, it were better to have peace with the president by ousting Mecklin, or peace with the public by retaining him.

But the result of these eight years of battle had strained no one more than Mr. Mecklin, the youthful, mustached, straight-forward scholar who had been brought to Lafayette to fill a chair especially endowed for him.

The first clash had come eight years before when he was called into the president's office and presented with a file of notes taken from his class-room lectures, and from that time on he had worried constantly over the conflict between his ideals and his sense of expediency. His ideal of academic freedom, his ideal of himself as a teacher, and a man—his ideal of truthall were opposed to what he knew was the easy way to find peace. For eight years he had fought, had been fought, had born the burden of the slander and accusations which come to a man only when he is the center of a controversy. Many a night during those years he had lain awake and worried, many a time he had tried to explain to President Warfield that he had reached his views by work and study, and logic, and could not conscientiously hold others, and many times he had experienced that half-hope, half-dream which comes to a young man in trouble—that all this fight could not be real, that his future could not be so troubled, that some time he would awaken and find he had been dreaming. But now, on that April afternoon, all his troubles were about to be made public, his wife lay dying of a slow disease, and John Mecklin was tired.

To his friend on the board of trustees who came to help him, he said what had come to be the inevitable: "I've been through this for eight years, how would it be if I resigned?" Then he picked up his hat and went out to the commencement ball game.

He must have realized as he walked across the campus that day that this was the first time he had ever given up when his freedom was at stake. He must have thought then back to the time when he had come to the Lafayette campus, expecting there to realize the freedom of inquiry he had dreamed of, expecting to put all his scholarship and years of hard preparation into his work at Lafayette for the rest of his life. John Mecklin felt that day for the first time the sense of futility, and of defeat.

But what defeat there was in Mr. Mecklin that day, the students whose questions he had answered even though truthful answers brought trouble, whose discussions he had fostered, whose thinking he had tried to broaden, turned into victory. For as he entered the stadium that afternoon, row after row of students rose, and long feefore he found his seat, the field echoed with the first cry of those who had heard the news—"Hurrah for Johnny Meek!," "Hurrah for Johnny Meek!"

John Mecklin's long fight for freedom at Lafayette is an important story in the annals of American academic freedom. The battle was won at Lafayette. Today one of his old students, Professor Harold Chidsey, occupies the former Mecklin Chair. To understand it fully, to realize that it had more than an individual meaning, that it was both a reflection of what colleges were then, and a force in making colleges what they are now, we must go back to the times.

It is always the task of the few to keep American colleges from rationalizing always the thinking of the times, to keep them forging ahead to new ideas, to new facts, and new ways of thought. Not until the twenties, in some cases not even now, have American colleges burst the bonds of the narrow theological creeds upon which most of them were founded. The histories of Dartmouth, Harvard, Yale and countless other colleges show the gradual relaxation of theological bonds to thinking, and even today we are not far removed from the time when every institution of higher learning in America answered its student's questions with "Thus sayeth the Lord."

That tight bond of theology was more than a way of life for American education. It was a barrier to thinking, a barrier to inquiry, a narrowing influence to every man who worked hard enough and learned enough to reach the stage where he wanted to work farther and learn more. That is what John Mecklin wanted to do, and the story of his fight at Lafayette stamps him at once as one of those few men who earn the right to fight for freedom.

Professor Mecklin is more than a fighter, though that in itself has stamped him with academic greatness. There is, as a matter of fact, just a little of the Mr. Chips in him. It is a something which makes students respect his judgment with a respect which is a peculiar balance between awe and love. It is the awe they feel for him which is, paradoxically, his only guard against the hero-worship he so dislikes. It is the love they have for him which made the students cheer and parade that day in 1913, and it is the • love they have for him today which makes Dartmouth men stamp their feet and applaud for minutes on end as he stands, silent and bowed at his desk, mentally and physically exhausted after his last lecture of a semester.

MECHLIN LOOKS THE PART

His appearance too, is in the best fictional tradition. His white hair, his erect carriage, the upright honesty of his Scotch-Irish features, his expressive face which twists itself into a thousand contortions when he is speaking—these are the earmarks of the "professor" of novels and of Hollywood. And that projectable character which forms the basis of the narrow Puritan creed he has described in books and lectures—those qualities of hard work, honesty, independence, and high moral standard—to which he has added depth and understanding—are an easily recognizable essence of himself.

But that is as far as the parallel goes. He says of himself, "I'm just an old, cranky, hard bitten Presbyterian with a lot of rough edges," and as the incident at Lafayette bears witness, John Moffat Mecklin is a rebel, a man intent upon freedom. He is also a thundering speaker, an occasionally brilliant writer, a Socratic conversationalist, a deep student, and something of an actor. The last is minor only—he uses it as a weapon with which to fight, and admits it. It is interesting to speculate on Mecklin as he is today, to discover if possible where that constant fight has brought him, in status and in thinking. Where has it brought him, this ceaseless effort of learning all that is within the existing framework, then tearing at the boundaries in order to be allowed to learn more?

It is probably true, as many have said, that on the Dartmouth campus today, seventy-year-old Professor Mecklin is the most important single influence on student thinking. His courses are always jammed to the last row of a large lecture room, and no student who enters it with narrow prejudice of religion or of economics leaves without having that prejudice jarred. An actual class room count demonstrates that more students "sit-in" on his lectures than in those of any other professor, and certainly his ideas have received the most widespread circulation. For example, the Hanover phrase, "It's a myth"—meaning a belief which has been proved unrealcomes from the puffed up class room cheeks, the magnificent of the arm, and the lectures of John Moffat Mecklin.

To alumni who want to know how the Dartmouth man thinks it is important to know how John Mecklin thinks. And, as with most men who lead honest and full lives, what John Mecklin thinks is not very different from what he has lived. It is almost a travesty on the work and fiber of any influential man to attempt in a paragraph an explanation of his ultimate philosophy. But students are always explaining the ideas of professors, and by this time, John Mecklin is somewhat accustomed to hearing his ultimate philosophy set forth like this:

His primary interest is in the study of ideas which underlie group thinking and group action. He traces to the present, for example, such ideas as Calvinism, the eglatarianism of Rousseau, the individualism which lies back of such slogans as "What's good for business is good for you." Such an interest carries him (and his classes) through the whole field of social thought as exemplified in such men as Plato and Augustine, Luther and John D. Rockefeller to the eventual thesis that all theologies and all systematic formulas for social conduct are rationalizations of the desires of specific groups, and that these rationalizations can be studied objectively, as a means of understanding the course of past and present events, and of predicting, in general, the social conduct of the future.

That is his consuming interest. His ultimate faith is but a further step. He bases his confidence in the democratic society of America on what he calls the "average man." That "average man" is the subject of a chapter in his best known book, AnIntroduction to Social Ethics. Mr. Mecklin defines him as the man who holds that set of beliefs which determine the tenor of American life, and pictures him as a product of a Calvinist theology of individualism, idealizing freedom, with a strong faith in moral values, a belief in hard work, and one who on questions of government and society can usually be counted upon to provide an answer which muddles through to a satisfactory solution. Mr. Mecklin traces through history the framework of ideas which determine the "average" man's thinking and believes that within that man lies a firm basis for the democratic way.

Those are, in essence, the fundamental beliefs of John Mecklin. One of his oftquoted class room remarks is that men do not think their way into their living, but live their way into their thinking. In typical Mecklin fashion he advises his students to "underscore that, it is basic." It is basic to him too, for the story of his life is analogous to the development of his thinking.

He was born in Mississippi in 1870 of Scotch-Irish parents whose emigration to America had been a revolt against English mercantilism, and whose traditional calling was the Presbyterian ministry. His father, his grandfather, his great-grandfather, two uncles and a brother in-law set the precedent, and John Moffat Mecklin was born, bred and forced into the Calvinist theology. Like a rebel and a thinker he bucked, and finally broke free. He remembers today committing to memory the shorter catechism, "What is God?", "What is original sin?" in order to compete for a Sunday school prize. Says John Mecklin today, "It just wouldn't go down."

Instead, he read George Eliot in his father's barn, and wandered along the banks of the river, exploring the marsh grass and fishing. But he learned enough of Calvinist theology so that when he went to Princeton Theological Seminary years later, he never had to study it, except objectively, as a peculiar phenomenon, and while he later rejected the intellectual framework of Calvinism, he took from it the essential basis for its structure, the reverence for ideas and the intellectual life, and the zeal for moral righteousness.

That puritanical background is not in any sense a paradox to what John Mecklin teaches. For while he may reveal in all its narrowness the Calvinist theology and relate it to the ruthless individualism of big business, that sense of upright moral righteousness, strong character, and hard work which was essential to Calvinism is apparent in his manner, his bearing and his conversation. He talks even today of meeting someone "after the tasks are done"; he neither smokes nor drinks, and one has the feeling that he cannot quite understand those who do; he gets "all wrapped up in a little book I'm writing"; he parcels out assignments in "little books" by the dozen to his classes and spends his vacation mornings in his study, locked away from everything but an intense interest.

His refusal to "swallow" the catechized answers to questions of theology was the first of his long series of revolts. His theological background he improved by hard work at Southwestern College, then in Clarksville, now in Memphis, Tennessee. There he pleased his Confederate officer teachers by memorizing an entire Greek grammar and writing an examination from 8 in the morning until 4 in the afternoon to win a two hundred dollar prize. At the age of eighteen he went farther, to the Union Theological Seminary in Richmond where he won a scholarship through his knowledge of Hebrew, and to Princeton, where he won two scholarship prizes in Greek, and delved for the first time into philosophy, psychology and classical civilization. When he could, he roomed with "Yankees." Perhaps it was the beginning of his tolerance.

For two years after finishing Princeton, John Mecklin followed his sense of obligation to the church which had educated him. Though by that time he was certain that his intellectual nature dominated his interest in pre-digested theology, he preached for one year at Dalton, Georgia. But his rebellious spirit was not happy, and with his first wife, he gave up the church forever and went abroad to study some more.

Four years at Germany with a Ph. D. at Leipzig, and he broke forever with theology in favor of the study of why those theologies were born. A year at Athens, and he learned to idealize and strive to make real for himself the freedom of the old Greeks, now necessary for himself if he was to break through the accepted boundaries in American thinking.

That freedom was the constant goal of John Mecklin from that time to now. His book on the Ku Klux Klan, his study of Fundamentalism, his book on the Medieval Saint, soon to appear, and his Introduction to Social Ethics—all are aimed at tolerance, and freedom. It was almost fictional, and certainly fitting, for him to hunt that freedom for himself all his life, and find it at last, at Dartmouth College.

In three years as a professor of Greek at Washington and Jefferson, he found none of it. "Most college presidents I knew before I came to Dartmouth," he says "were a spineless lot of pussyfooting politicians."

Four universities vied for his services after his resignation from Lafayette. He chose Pittsburgh where he established a philosophy department, did his first administrative work, risked trouble with the financial tyranny of the University by helping to establish a Civil Liberty League during the great steel strike of 1919. and finally left for Dartmouth.

Professor Mecklin remembers his first night in Hanover and a sign in the Hanover Inn reading, "Guests who leave windows open will be held responsible for frozen pipes." He remembers that in President Hopkins he found immediately his ideal college president, a man to whom the freedom he had searched and fought for was a thing highly prized, and always maintained. Unconfirmed student gossip puts the meeting between the President and the Southerner this way: President Hopkins: I want you to teach sociology.

Professor Mecklin: I'm not interested in theoretical sociology. I'm interested in the ideas which lie back of group thinking and group action.

President Hopkins: Then I want you to teach a course in that.

He remembers that at Dartmouth he realized his goal of perfect freedom to teach what he had learned, not as the final word to any student—"l don't think I have the right"—but as his contribution to the student who was searching his own final word. Where Lafayette's tyranny had been theological, where Pittsburgh's had been economic, John M. Mecklin found no tyranny at Dartmouth, and "no one will ever appreciate what Dartmouth is, and what it stands for, who has not come from a background such as mine."

FREEDOM NOT TAKEN FOR GRANTED

Perhaps it is his own fight for freedom which makes him skeptical today of the undergraduate appreciation of that freedom he helped to gain. Freedom for him was something he worked to get because he needed it. Freedom for most Dartmouth men is something they are born into, and never learn to use. The undergraduate of today, Professor Mecklin believes, has a better background, a more inquiring mind, and a far richer opportunity than had those of three decades ago. But he doubts that most of them made good use of it.

What John Mecklin, looking back at almost seventy, means by using freedom is almost tragically hard for us to understand today. If there were ever students at Dartmouth whose highest aim was to study in Athens, whose greatest. delight was to explore some little known text by some obscure priest, whose physical and almost spiritual drive to learn, learn, learn, possessed every moment of their lives, most of them have long since graduated. And John Moifat Mecklin is today a sort of living monument to the time when freedom meant something to work for, something to fight for, not simply for the sake of freedom, but because all that existed within previous boundaries was explored—and a man was ready to go farther and explore more.

It has been twenty seven years since John Mecklin fought for that kind of freedom at Lafayette. The undergraduates who cheered him then might not recognize him today. But the things they cheered him for are now a part of the liberal Dartmouth tradition.

They see him spinning out an idea in front of an intent class, trying hard to explain something he knows is important, and wants them to know it too. They see him walking down the street in winter, with his fur cap covering nearly half his face, stopping to grab a student's arm, and ask him questions, or in summer time, pausing by the senior fence to watch a campus ball game. They see him heading up the river early on a Sunday morning for a day's fishing in his motor boat. And they watch his bronzed and wrinkled face on the next Monday when he says, "Every time I go fishing with those Vermont Republicans I learn some more sociology." They see him bidding them goodnight on the porch of his home, the light shining directly on his white hair, and seeming to reflect out on the drooping branches of the pines. And they hear him say, "That grass is a sort of hobby with me. I've always liked things that covered up the rough spots."

They see him, and sometimes they may reflect that what he is really trying to say to them is that the freedom he fought for is no empty abstraction, that no man has the right to freedom unless he needs it, unless he works hard enough to get it and is willing to use it well once it is attained. And if they know him well enough, they may reflect further that John Mecklin is in himself a better demonstration of this thesis than anything he can say.

Bouchard.

THOMAS W. BRADEN JR. '40 Editor-in-Chief of "The Dartmouth," author of the biographical profile of Professor Mechlin in this Undergraduate Issue.

EDITOR OF THE DARTMOUTH

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDartmouth Mourns Passing of Craven Lay cock

May 1940 -

Article

ArticleI Found Seven Latinos

May 1940 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915*

May 1940 By CHARLES R. TAPLIN, RUSSELL B. LIVERMORE -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

May 1940 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

May 1940 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, H. WARREN WILSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935*

May 1940 By GARDNER CUSHMAN, DONALD W. FRASER

Thomas W. Braden '40

-

Article

ArticleAutumn Days

November 1946 By Thomas W. Braden '40 -

Article

ArticleA Clear Line

February 1947 By Thomas W. Braden '40 -

Article

ArticleA Popularity Poll

April 1947 By Thomas W. Braden '40 -

Books

BooksINDIRECTIONS

April 1947 By Thomas W. Braden '40 -

Feature

FeatureOur Battle To Reform The Education of Teachers

DECEMBER 1964 By THOMAS W. BRADEN '40 -

Article

ArticleThe Freedom to Choose

OCT. 1977 By THOMAS W. BRADEN '40

Article

-

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT HOPKINS AND MR. PARKHURST VISIT THE PACIFIC COAST ASSOCIATIONS

May 1920 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Club Luncheons

February 1949 -

Article

ArticleWith Big Green Teams

December 1957 -

Article

ArticleFall Reunions

SEPTEMBER 1982 -

Article

ArticleThe Orange on Campus Is Not on Leaves

OCTOBER 1996 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

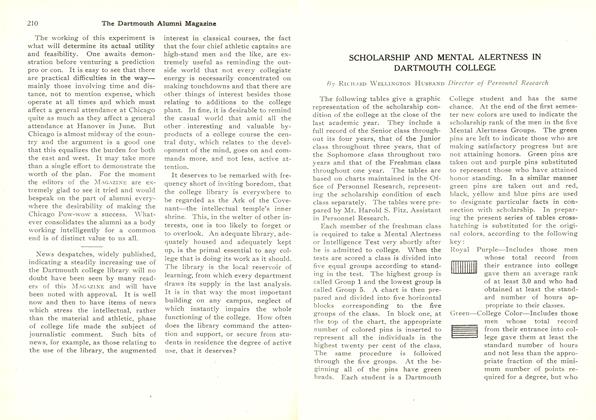

ArticleSCHOLARSHIP AND MENTAL ALERTNESS IN DARTMOUTH COLLEGE SCHOLARSHIP AND MENTAL ALERTNESS IN DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

January 1924 By Richard Wellington Husband