The Probability of the Impossible is Subject of President's Address to Student Body and Faculty

The complete text of President Hopkins' address September 18 openingthe 173rd year of the College follows:

FOR US TODAY, GATHERED TOGETHER FOR utilization of the educational facilities which Dartmouth offers, there is one essential fact to keep in mind. The values of a liberal education and of cultural development are immeasurably greater now than in more stable times. As recipients of special privilege which leaves us free to seek these values, obligation rests upon us to develop the capacity to utilize them intelligently. Unfortunately, residence in an academic community is not good for all men. Mere casual contact with educational standards does one little good and may do one much harm. The self-assurance of men who on the basis of superficial knowledge jump to easy conclusions is no contribution to society at any time and in time of emergency may become a positive menace. To the extent that there be any among you without the seriousness of purpose to strive, without the ambition to know, and without the will to do, the effectiveness of the College as an agency of helpfulness in a troubled world is weakened.

Not only do we need to know more than ever before about the world outside our- selves; it is important likewise more completely to know ourselves. We need to know what is our susceptibility to harmful influences and what is our callousness to worthy impulses. The capability of appraising our own qualities intelligently is vital to our own ultimate self-satisfaction, as also it is indispensable for our applying these constructively in such a period of crisis as is the present.

The time is gone, if it ever existed, when the years succeed one another under like conditions, when circumstances which governed the lives of the fathers govern the lives of the sons, and .when details of the chart of life remain a constant from generation to generation. But this does not mean that lessons derived from experiences of the human race through thousands of years of development have become valueless or that the vast stores of knowledge which mankind has accumulated from age to age can without hazard go unstudied. It does mean that in the indispensable consideration of such material, more intelligence in interpreting facts, more discrimination in forming judgments, and a nicer sense of light and shade in accepting conclusions are vital for the more delicately adjusted social and political relationships of modern times.

We hear much insistence from time to time about putting first things first. This is essential, of course, but there is even more necessity for some reasonable definition of what constitute "first things." It is to the end that men like yourselves may as early as possible become skillful in appraisal of life's values and accurate in definition of the relative importance of these that Dartmouth was founded and that it proffers its advantages to you today. Mr. Churchill has said that the first responsibility of liberalism in these days is to survive. Survival, however, has become a far more complicated matter than simply being stronger than one's opponent. It is dependent upon when and how and where strength is used. Rationalization, moreover, has long ago been found wanting as a guide. After Crete, one of the English newspapers editorialized to the effect that the Government had always been prepared for the obvious but never for the improbable. We are coming to understand that such phrases as "It isn't likely" or "It couldn't be" are dangerous narcotics. Of two extremes, the safer principle for acceptance today is Tertullian's dictum, "I believe because it is impossible." This, however, requires a flexibility and an adaptability of mind with which education has had little occasion in the past to concern itself. Its concern has been largely in cultivating strength of mind. Adaptability is something more than open-mindedness, which is a passive state; it is an equipment in mental forces and in instinct for mobilizing these quickly for meeting new and unexpected situations. Reality has been revealed to us as meaning something far beyond that which is obvious.

If there is any one lesson of history more convincing than another, it is that those who lose touch with the realities of their time lose all. The narratives of history are filled with instances of peoples who have overcome the natural difficulties of physical environment, have acquired some degree of material prosperity, have progressed culturally and have developed many of the desirable attributes of civilization; yet who, when seemingly on the threshold of grand accomplishment intellectually, nevertheless have shown themselves lacking in the very characteristics by which previously they had made their progress. So they have passed into oblivion. This invariably, I think, has been due to the fact that the respective peoples have lost their touch with reality and have unconsciously set up or accepted false standards by rationalizing or by theorizing from fallacies based on their desires rather than on actuality.

It is a disquieting reflection to consider how many of our own problems of the present and of the recent past may be ascribed to the fact that we have reasoned according to our impulses or to our wishes or to our hopes rather than with our minds. In our eagerness to escape struggle and hardship ourselves, or in the case of older people more particularly for our children, we have set up an enervating thesis that every one is entitled to security regardless of his own effort to secure this and we have given not only respectability but almost sanctity to a doctrine of "safety first."

FORCE OF MIND AND HEART, Too

When preponderantly among the peoples of the earth, might reigns and gives its own perverted definition as to what constitutes right, at such a time right, as defined by the mind and conscience of man through the ages, must oppose might with greater might, if it is to survive. For the time being, the theorizing of contemplative hours and the experimentation by trial and error to find a better form of life have to give way to the stark reality that what we cannot defend by adequate force, we cannot keep; and that even an imperfect civilization is preferable to a society lacking any capacity for self-improvement.

Having said this, let us recognize at once that the force essential for defense is not exclusively physical force, indispensable as this unquestionably is. It is as well the force of mind and heart. Much as we abhor the purpose to which the Germans were for years conditioned to attempt domination of the world, the thoughtful observer cannot forego a grudging admiration for the scope of the planning that was devised, for the unity of purpose that was secured, for the details of organization that were mastered, and for the efficiency of operations when at last these were undertaken.

However mistakenly applied, the bid of Germany for world domination has been the result of originality of thought, of mental concentration, and of self-discipline to an extent unprecedented in world history before. To those of us who do not believe that good can live by appeasement of evil, it seems clear that these qualities, typical of Germany's planning for world conquest, define the nature and characteristics of qualities necessary to defeat them. Nothing less than theirs in intensity of purpose, in mental acumen, or in willingness to undergo the exactions of physical hardihood can be effective.

In the sharper focus today than ever previously on what the influence and effect of higher education ought to be, I think that we shall see again what the founders of our colleges saw as a necessary concomitant of education and what has been long ignored—the responsibility for inculcating something of a spirit of evangelistic zeal for the establishment and maintenance in the world of the Christian virtues. The whole principle that men should be educated for recognizing their functions as sons of God and members of a great brotherhood goes into the discard beyond recovery, along with respect for beauty and truth, under Nazi reasoning. It is the abandonment of all such conceptions that enables the Hitlerites to ignore the obvious answer to Cain's query to God whether he was his brother's keeper, and by corruption and betrayal to impose ruthless suppression on races and peoples helpless to defend themselves against sadistic savagery.

Against higher education grave charge may be filed, moreover, that in its own narrow conception of itself simply as a purveyor of sterile scholarship lies much responsibility for our own national reluctance to recognize obligations. If we can genuinely argue that we have no responsibility to offer our powerful protection to brother human beings abroad against the brutalities imposed upon them by the arrogance and contempt of their conquerors, it will be a short step to like argument in regard to our brethren at home. If as a result of the education which the College offers, no sense of obligation is acquired by the student as to how knowledge shall be applied, it can well be argued that there is little justification in the college accomplishment for all of the anxious solicitude, for all of the altruistic thought, and for all of the self-denying generosity which has made possible the institutional structure of higher education in America. Nothing is clearer than that we shall never be free from threats of war or from war itself until intellectualism has accepted the fact that no people can live to itself alone in a world as small and as closely knit together as our world has become.

An ancient fable pictures God as creating man and then, finding how helpless he was, making men. Thus accomplishment became possible through cooperation of varieties of talent that otherwise would have been impossible. This diversity of thoughts and aptitudes, however, introduces difficulties likewise. No college official would doubt John Lock's statement that the great problem in education is that men's minds differ as greatly as do their faces. Moreover, in addition to the diversifications of nature, there are those of environment—of home upbringing and of community associations.

It is under such circumstances that a common ground is so difficult to find in democratic countries under the philosophy of individual self-determination. On the contrary, unanimity can be prescribed and enforced by the Axis. Totalitarianism can endure no competition in exercise of authority. Hence it destroys the Church, the School, and subordinates family relation- ships to authority of the State. It sets up falsehood as truth and requires acceptance of this. It develops a make-believe structure of society and asserts this to constitute a superior race. It asserts a fictitious dogma to be learning and imposes this on youth as education. It utilizes the instinct of man to classify phenomena in terms of familiar analogy by characterizing the present conflict as war, thus leading us to think of it and to discuss it in terms of previous wars.

Thus we are led away from seeing it as it is,—an attempted world revolution of a kind and of a magnitude never before imagined by the mind of man, which is utilizing the processes of war to destroy andecency and right. Thus, if the war is successful, there will be left a void into which brutality and savagery may be injected, establishing a new world order. As Mr. Lippmann has made clear, the dynamics of totalitarianism require ever spreading and always continuing war. From this permanency of war the democracies have no cape, and no approach to peace is open to them, except by military defeat of the Totalitarians.

Such are some of the aspects of the immediate situation. However, it is inconceivable that eventually, after the conditions of withholding positive action have become clear, the forces of liberalism shall not assert themselves to preserve the principles of liberty and the blessings of freedom, for the establishment of which so many have struggled so long. The immediate stress of the existent emergency will vanish before any considerable proportion of the span of life of men now undergraduates has been covered. Then new conditions will require the unhurried and thoughtful consideration of educated minds, for development of which the College strives. This is why the College still educates for peace rather than supplanting all of its effort with training for war. Walter Bagehot, in discussing the late development of pure science, quoted Pascal's saying that most of the evils of life arose from "man's being unable to sit still in a room." "Most men," said Bagehot, "inherited a nature too eager and too restless to be quiet and find out things; and even worse—with their idle clamour they 'disturbed the brooding hen,' they would not let those be quiet who wished to be so, and out of whose calm thought much good might have come forth." I cite this passage because of the imperative necessity in years to come for carefully considered action, when once the present crisis is passed. Preparation for this is particularly a college responsibility. Bagehot says further, "Prerequisites of sound action require much time, and, I was going to say, much 'lying in the sun,' a long period of 'mere passiveness.' "

RECONSTRUCTION AHEAD

Nowhere in life are opportunities for such contemplation as readily available for the average man as in an undergraduate course in a liberal college. This is true' even in the war-torn world of today. It would be tragic misfortune in days like these for any single one of you to be unconscious that an opportunity is yours which can be made accessible to but a few. Not only must a present emergency be met but, as President Roosevelt has said, "Later we shall need men and women of broad understanding and special aptitudes to serve as leaders of the generation which must manage the post-war period."

As last June I said to the class just graduating, so today to you who will be the post-war generation may be repeated God's promise to his children if they would "satisfy the afflicted soul": "Then shall thy light rise in obscurity, and thy darkness be as the noon day:.... and they that shall be of thee shall build the old waste places; thou shalt raise up the foundations of many generations; and thou shalt be called, The repairer of the breach, The restorer of paths to dwell in."

THE COUNTRY FACED A GRAVE WORLD CRISIS IN 1916 WHEN PRESIDENT HOPKINS WAS INAUGURATED 25 YEARS AGO THIS MONTH

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDartmouth Again Faces A World Crisis

October 1941 By WM. STUART MESSER -

Article

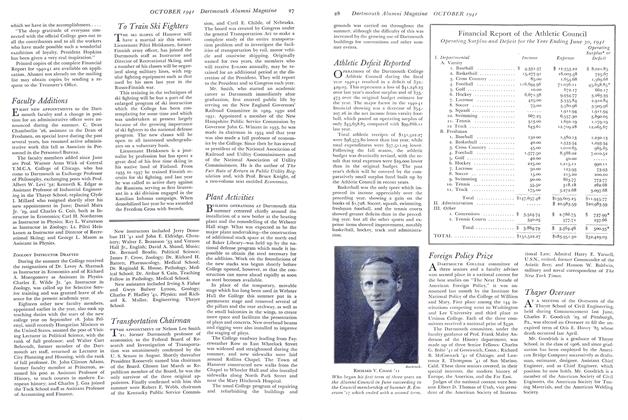

ArticleFavorable Financial Year

October 1941 By Alumni Fund and Over Two Millions Added to Assets -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917*

October 1941 By EUGENE D. TOWLER, DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912*

October 1941 By CONRAD E. SNOW, RICHARD C. PLUMER -

Article

ArticleOut-Of-Doors Disciple

October 1941 By ROSS McKENNEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

October 1941 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR

Article

-

Article

ArticleMasthead

AUGUST 1929 -

Article

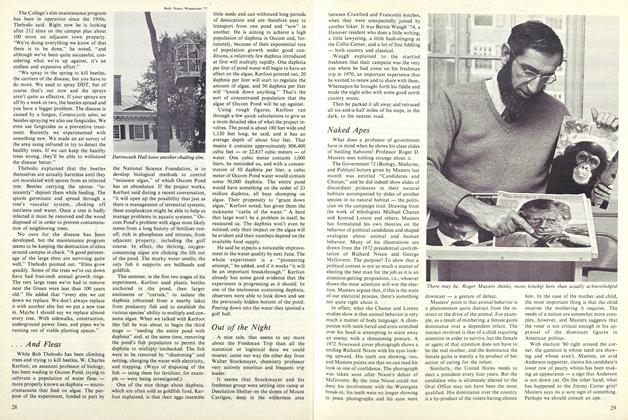

ArticleNaked Apes

October 1980 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

Sept/Oct 2010 By BONNIE BARBER -

Article

ArticleThayer School

NOVEMBER 1971 By J.J. ERMENC -

Article

ArticleSeniors Interview Their Elderly Future Selves

MAY 1992 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Article

ArticleWE CAN'T BELIEVE IT

April 1934 By S. H. Silverman '34