The deliberative approach is not a luxury in complex times.

College presidents are frequently criticized for not using the bully pulpits of their office to speak out on important issues of the day. They are compared unfavorably to presidents of bygone eras, when giants are said to have walked the land.

"A generation ago...college and university presidents cut striking figures on the public stage," The New York Times mourned recently. "They called for the reform of American education, proposed safeguards for democracy, sought to defuse the cold war, urged moral standards for scientific research, and addressed other important issues of the time. Today, almost no college or university president has spoken out significantly... about dozens of.. .issues high on the national agenda."

College presidents of a prior era were, indeed, visible figures in the nation and in their communities. They wrote rows of books, published articles in the Atlantic Monthly, and chaired national commissions. They were members of the country's unofficial House of Lords: of eminent dignity and beyond popular election.

Nicholas Murray Butler, the legendary president of Columbia from 1902 to 1945, wrote more than a dozen books and also won the Nobel Prize for Peace. Yet Butler lived at a pleasant, uncrowded time. He could sail to London on Memorial Day to spend a summer in England full of reading and reflection; he dined with the rich, spoke with the wise, and returned to New York on Labor Day. Of course he had time to write.

When my colleagues and I encounter unfavorable comparisons to presidents of a half-century ago, we are tempted to protest in self-pitying terms: "We have much more demanding jobs than our predecessors. We preside over institutions that are more complex and more publicly accountable. We have to spend more time raising money. We have to pay more attention to a larger set of constituencies—faculty, students, staff, alumni, the media, and foundations— which are more vociferous and less monolithic than they were earlier in the century." Little wonder, we persuade ourselves, that we may not speak out on important issues as readily as our predecessors did.

Presidential self-pity, it may be salutary to recall, is not a new phenomenon. Edward Holyoke, who was president of Harvard College for 32 years, from 1737 to 1769, is supposed to have said on his deathbed, "If a man wishes to be humbled and mortified, let him first become president of Harvard College."

My own view is that the public ought pity us not. We asked for these jobs and get great satisfaction from holding them. It may even be that the allegations of timidity are overstated. Many contemporary presidents have been exemplary in writing books and addressing important issues of public policy, especially those involving higher education. I think especially of the leadership of Father Theodore Hesburgh of Notre Dame and Derek Bok of Harvard, to mention only two not now serving.

What, then, fuels this image of college presidents as timid and uninvolved? In part, it is simple competition for available time in a crowded spectrum of media outlets. And in part, of course, it may be accurate. The truth is that college presidents today face a proliferation of administrative responsibilities and internal pressures created by the ethic of constituency participation and consultation; that ethic was far less expansive a half-century ago. Although chosen for their leadership capacity and educational vision—indeed, every board of trustees hopes that, in appointing a president, it has found another John Dewey or Alfred North Whitehead—once presidents take office, they spend much of their time on fundraising, alumni relations, and ceremonial activities. (All of us who are presidents find that the most likely places to renew our acquaintance with other presidents are the airline lounges of LaGuardia and O'Hare airports.)

They also preside over institutions that are microcosms of the larger society to a much greater extent than were colleges of a generation ago, and that reflect the ideological tensions of that more democratic society. They often find themselves hemmed in by spoken and unspoken pressures from numerous and multi-faceted constituencies, especially on such sensitive and polarizing issues as racial diversity, ethnic separatism, sexual harassment, multiculturalism, and political correctness.

"Every idea," as Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. once said, "is an incitement." And for every controversial idea that a college president espouses, there is a constituency whose goodwill he potentially jeopardizes. He may be respected for his courage by those who agree with him, but his college will lose the support of many who do not. No president wants to make new enemies for his college. Many therefore believe that the price to be paid for what seems to be the indulgence of stating their convictions is simply too high.

And yet there are important issues on which college presidents can and should be heard. In today's fast-paced world, presidents need to remind their audiences that not every response can be immediate. The deliberative approach is not a luxury in complex times. If college presidents are to be effective public intellectuals, participating in national policy debates in a visible way, they must carve out more time to read and think and reflect. They need to liberate themselves from a multitude of demanding tasks, many only tangentially related to education.

The gratifying fact is that most college presidents appreciate that the privilege of holding a position of leadership in higher education imposes the responsibility of speaking out on public issues, especially those affecting higher education. The challenge is to approach that responsibility with the same dedication and energy they use to lead their institutions, anD to remember, as Justice Louis Brandeis wrote, that "if we would guide by the light of reason, we must let our minds be bold."

JAMES O. FREEDMAN'J- Idealism and Liberal Education recently won the Ness BookAward from the Association of American Colleges and Universities.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

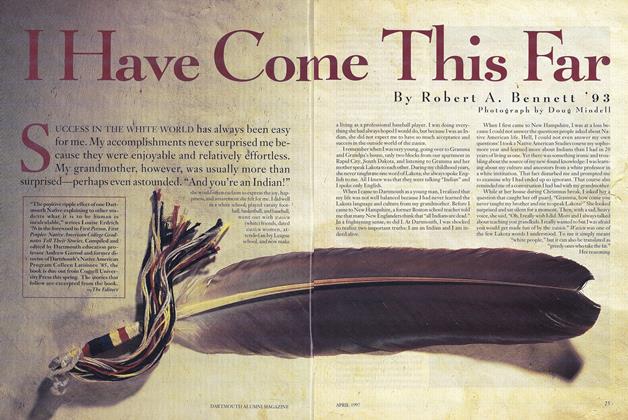

Cover StoryI Have Come This Far

April 1997 By Robert A. Bennett '93 -

Feature

FeatureNative America at Dartmouth

April 1997 By Karen Endicott -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWhy Don't You Say Anything?"

April 1997 By Davina Begaye Two Bears '90 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMy Grub Box

April 1997 By Vivian Johnson '86 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryI Dance for Me

April 1997 By Elizabeth Carey '93 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWe Are Not Your Indians

April 1997 By Arvo Mikkanen '83

James O. Freedman

-

Feature

FeatureThe President's In-box

June 1987 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Article

ArticleMY HEROES

MARCH 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Feature

FeatureHONEST TO GOD ACCOMMODATION

OCTOBER 1991 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Article

ArticleWorries of a President

May 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Education Gap

January 1996 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Uncertain Future of Medical Education

DECEMBER 1997 By James O. Freedman

Article

-

Article

ArticleOUTING CLUB EXPLORERS VISIT MANY CLIMES

JANUARY, 1927 -

Article

ArticlePolitical Experiment Grows

June 1938 By C. E. W. -

Article

ArticleWhere Wheelock's Great Design Began

DECEMBER 1965 By FREDERICK CHASE '05 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

DECEMBER 1964 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

APRIL 1965 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticleTuck School

December 1957 By R.S. BURGER