Prof. Adams' Analysis of the Gospels Defies Tradition; Ben Ames Williams' Recent and Important Novel

by David E Adams 'iy, Harpers & Brothers, New York, 1941, 201 pp.

AWARE OF THE common skepticism as to the . validity o{ the Gospel accounts of early Christianity, Professor Adams adopts an ingenious technique which meets the doubters on their own ground. He winnows the wheat from the large quantity of chaff. He ruthlessly examines each paragraph of the first three Gospels to find the core of truth embedded in the first century symbolism. He presents a "real" Jesus by stripping him of the glamorous garments draped over him by second-generation followers.

The Gospel writers, according to Dr. Adams, "confronted with the problem of portraying a personality that seemed to transcend the normal categories," had difficulty in finding adequate methods to "convey the impression of his spiritual stature" and power. Conscious of the fact that "the greatest cannot be spoken" because there are no words to say it, they resorted to concepts developed in the only Bible they knew. The most common modes of expression are: the "Man of God" pattern, pictured in the Abraham-Moses-Samuel-Elijah tradition, of which fifteen "well-marked characteristics" are listed; the prophetic pattern, with the concepts of the Messiah and the Suffering Servant; and the idea of sacrificial atonement.

The analysis of the Gospels in the light of these Old Testament patterns would shock any traditionalist. The birth stories are late "Man of God" embroidery. All of the miracle stories fall into one of two categories—they are either parables and didactic tales, or they are distortions of actual episodes in which no natural laws were violated; "it was not reported miracle that made the man great," but "it was the spiritual greatness of the man that gave rise to" such stories. Jesus' chief problem, in which he failed, was to convince his people that he was not a "Man of God" wonderworker, which the writers tried to make him, but an ethical and religious teacher of the prophetic tradition. The "Confession of Peter" is an anachronism, for Jesus never thought of himself as the Messiah. The "Good Samaritan" and other parables unique to the third Gospel were probably not the actual words of Jesus, but rather "Luke's characteristic literary method" or "his technique of dramatic portrayal." The Passion Week record, marked often by "cynical realism" and by many "bitter and vituperative words," "ill accords with the Jesus' portrayal elsewhere of the Father in heaven," and reflects' rather the later resentment and hatred toward his executioners. Accounts of the "Transfiguration and of the postresurrection appearances were reports of vivid dreams. Authentic teachings of Jesus were conditioned by the fact that he and his people lived for decades, in effect, in a Roman "concentration camp."

Such examples show that this provocative book is no "milk for babes." Dr. Adams is tough-minded in his handling of his materials. Something of the "granite of New Hampshire," which found large place in "the muscles and the brains" of the distinguished father (professor of Greek at Dartmouth for thirty-four years), characterizes the work of the son. His direct and precise style is often eloquent. His reconstruction of the Jesus that survives the analysis, a stirring last chapter, includes an outline of the unquestioned facts in the life of the Great Teacher, and explanations of the sources of his personal powers. Through such an honest study of the documents, "we discover," in the words of the author, "the character and influence of a man whose profound consciousness of the reality of God, whose vision of a high way of human living, and whose spiritual power, left a permanent mark upon the life of his time, and a priceless legacy of insight to the centuries to come."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters From Bolte

November 1941 -

Article

ArticleDistinctive Student Achievement

November 1941 By BILL CUNNINGHAM '19 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917*

November 1941 By EUGENE D. TOWLER, DONALD BROOKS -

Article

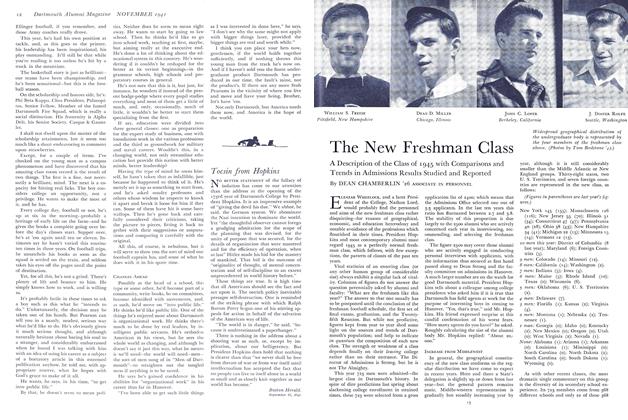

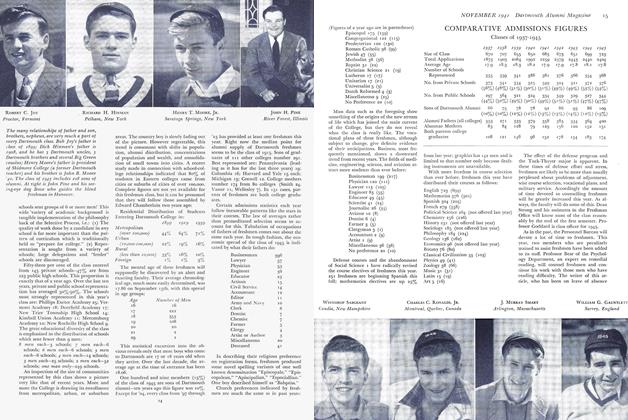

ArticleThe New Freshman Class

November 1941 By DEAN CHAMBERLIN '26 -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

November 1941 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1938*

November 1941 By CARL F. VONPECHMANN, J. CLARKE MATTIMORE, DAVID J. BRADLEY

Roy B. Chamberlin

-

Books

BooksA STUDENT'S PHILOSOPHY OF RELIGION

May 1935 By Roy B. Chamberlin -

Books

BooksTHE CHILD'S WORLD IN STORYSERMONS

November 1938 By Roy B. Chamberlin -

Books

BooksFROM WHENCE COMETH MY HELP

March 1940 By Roy B. Chamberlin -

Books

BooksGREAT COMPANIONS,

April 1942 By Roy B. Chamberlin -

Books

BooksTHINK ON THESE THINGS,

May 1942 By Roy B. Chamberlin -

Books

BooksEARLY ENGLISH CHURCHES IN AMERICA

November 1952 By ROY B. CHAMBERLIN

Books

-

Books

BooksDeaths

June 1948 -

Books

BooksGROWTH HORMONES IN PLANTS

November 1936 By Charles J. Lyon -

Books

BooksFLAMES OF LIFE: A PICTORIAL PHILOSOPHY.

May 1961 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25 -

Books

BooksTHE HAPPY END

June 1939 By H. G. R. -

Books

BooksDRIFTWOOD: MAINE STORIES.

April 1974 By ROBERT H. Ross '38 -

Books

BooksSorting Out the Roses

OCT. 1977 By SAMUEL M. PRATT '41