Outstanding in His College Generation Stubby Pearson '42 Represents Qualities the College Seeks in Students

WHEN, AS A PRACTISING ALUMNUS, I think of Stub Pearson, the time honored parable about the promenading rooster comes promptly to mind. According to this lilting legend, the head of the hen yard stepped out for his accustomed constitutional one rose-kissed dawn, and all went about as usual until he rounded a bend at some distance from his seraglio and found, ker-plunk, in his path a full-sized ostrich egg. He'd never seen, nor even heard of, anything like it before in all his life, but, after satisfying himself that it was, indeed, a piece of glorified hen fruit, he painstakingly rolled it by easy stages, back to his home base.

Arrived there with it safely, he paused sufficiently to catch his breath and recapture his dignity, after which he went around carefully waking up the hens. When they all were assembled, he said, "Now, Girls, I don't want any of you to think I'm finding fault. Still I don't think any of us should ever be too complacent about our work. Apparently, this is the sort of'thing that can be done with proper effort. All I ask for the moment is that you keep your eye on it, and do the best you can!"

There's a difference between buying a student and selling your college. Dartmouth alumni are in the legitimate business of selling a magnificent product to the youth of America—their college, and all it represents and strives to be. But the college is no bigger than the product it works on, and in plain Storr's Bookstore English, if you can find any more Stubby Pearsons on the loose in your district, in the name of a Character prominently mentioned in the New Testament, sell him Dartmouth— for his sake, and ours, and the worlds.

The chances are you won't be able to, for there aren't very many of them, but, at least, you can keep your eye on this egg and do the best you can.

I'm talking about this year's Dartmouth football captain, but don't let that fool you. Football, and even basketball, which he likewise captains—the double leadership giving him rare college distinction—are only incidentals in this personal story.

This rawboned giant from the wheatlands of Minnesota is one of the really great leaders of Dartmouth undergraduate history—on the field, in the class room, on the campus, in the community. Every honor the students have to bestow, every prize an undergraduate can honestly earn are his, and he wears them with a self effacing. modest grace that shows they haven't been misplaced.

I don't know what higher compliment could be paid a boy than this. Maybe I shouldn't write it, for it came in personal conversation, but, to me, it seems supreme. Not only the supreme accolade of his college to an undergraduate, but a comforting incidental message to those of us concerned about our nation, and anxious to know just where representative college youth stands concerning it, as well.

It was President Hopkins speaking, and, as I say the conversation was private, and I really don't remember how young Pearson's name came into it, but the President nevertheless said, "I was deeply concerned when I heard Pearson was making the rounds of the various pacifist meetings which were being held at various places on the campus last year. I was concerned because I knew Pearson could swing the undergraduate body. No youth in my years as President has had such a complete hold upon students as Stub, with the possible exception of Bob Michelet. I felt he could lead them anywhere.

"As diplomatically as I could, I made it my business to find out why he was attending these various gatherings. I was greatly relieved when it developed that he was merely attending through intellectual curiosity. He wondered what they had to say—and he decided that it wasn't enough." If anybody can top that for tribute, I stand corrected.

I suppose, if anybody wanted to get up and squawl about it in the fashion that's been occasionally done they could call Stub Pearson a proselytyzed athlete. The trouble is there was so much hysterical squawling over another Minnesota kid named Bob Krieger, one of the most legitimate students whoever selected Dartmouth on his own and then paid his own way, that Pearson, an even bigger whale, slipped in all unnoticed by the yammering you-know-what's.

I don't chance to know whether he's receiving financial aid from the college, except that, this year, he's a Senior Fellow, which is something new since you and I were young, Maggie, and which means that he doesn't pay the college anything, nor, as nearly as I can figure out with my 1.6 brain, isn't beholden to it for anything, not even classes, hour exams, bawlings out from the dean nor stale jokes from the faculty.

His pater familias owns and operates a successful garage and automobile sales business in the not exactly gigantic metropolis of Madison, Minnesota, which is a couple of hoots and a holler on west of Minneapolis toward the South Dakota line, and so far as I know, the young man is in plenty of personal funds. But, even so, the blethering blue-noses might, and with some mechanical jus tification, point the quivering finger at Ozzie Cowles, Dartmouth's now nationally famous basketball coach.

The boy wanted to play basketball at Dartmouth under Coach Cowles, and Ozzie Cowles did see him during the State Basketball Tournament in Minneapolis, that being Cowles' home district as well, and Cowles being there on vacation at the time. If reporting such is treason, get the rope.

Pearson, himself, tells it an entirely different sort of way.

HEADING EAST TO COLLEGE

Cowles was originally the basketball coach at Carleton College out in that general district, where the wind occasionally blows so hard a man can hang his hat up without a nail, and it snows so hard in the winter that a man riding horseback in a stove pipe hat is no more than even with the top of the drifts. They're basketball crazy all out through that region. Stub was the gleaming star of his high school team and both his high school coach and his superintendent of schools had played basketball under Cowles at Carleton.

Stub got the idea that he wanted to go to an eastern college. His folks were against it. The community was thunderstricken. The University of Minnesota is the Oxford of that district, and it's a magnificent university, brethren, you ought to see it. It's supposed to be the goal of dreams for every normal Minnesota boy and girl, but just the same, says Stub, he felt he'd like to "go east."

If he were determined upon this sort of heresy, his sorrowing superintendent and high school mentor told him, at least it might save some portion of his soul to try a place called Dartmouth where a Minnesota man, their old coach, Ozzie Cowles, was coaching basketball. They'd write Oz, they said. They did, and he punted over, come summer, in his wheezing puddle jumper to confer with the young candidate for eastern culture, who had meanwhile applied and been admitted to Dartmouth.

If that's proselytyzing, Stub's one of 'em, but it wasn't, and he isn't.

The young man landed in Hanover, a tall, rawboned country boy with walking beam shoulders and hands like twin bunches of bananas, but he had the sort of eyes that look beyond the horizon. That nickname, "Stub" is one of those other-way-around affairs, such as a tall man called "Shorty" and a globular burgher termed "Slim."

Pearson, as a matter of fact, is 6 ft. 3 in. tall and, in his gridiron regimentals, he'll hit a solid 220, possibly. They carry him at 198 in the football statistical sheets, but, as honest and upright as the Whitey Fullers of the autumnal typewriters otherwise are, as good to their families and on as cordial terms with their pastors, the gridiron publicists of the colleges are the golwhoppingest fibbers when it comes to putting down what their gladiators really heft. It comes under the head of strategy, one supposes, but anyhow, Stub Pearson is what they called, in my time and maybe yours, "a husk."

He's about a dead ringer, physically, for the famous Texan, John Kimbrough, and he doesn't look unlike Jarrin' Jawn in the features. Pearson has a handsome face, incidentally, which still leaves him looking like John, for that's John's engaging kisser you've been seeing on billboards all summer, posed as an Army Air Corps Cadet in the big Chesterfield ads.

Pearson hasn't posed for any billboards, and from what I know of him, he isn't likely to, but I'll say this—he could, and without spoiling the scenery.

Stub's athletic background in high school is interesting and even prophetic. His little Dawson High School—his family removed to nearby Madison later—possessed a grand total of 199 students, the football squad but 20 players. Stub was football captain. He played fullback when his side had the ball, end, when it didn't. If anybody got hurt he filled it wherever it was. The net result was that in three years, he played several full games in every position on the team.

The basketball squad had a roster of 10. Stub was practically 81/2 of 'em.

In the matter of studies, usually only a necessary evil in the lives of most of us athletes, he took every honor the school had to offer, and hit the jack-pot at graduation with not only the vote as the best student of the year, but likewise as the best student in all the school's history.

That football versatility carried right on into college.

On his freshman team, he played end. Spring practise that year proved the varsity was lacking a center. Pearson was switched over to the middle and played every major contest of the 1939 season as varsity center without relief.

Next year, which was last year, Pearson accomplished a football feat, or the coaches accomplished it with him, that is practically impossible in these days of gridiron complexities and specializations. Two weeks before the now practically legendary Cornell game (the famous Fifth Down classic) Pearson was given the Herculean task of playing center on offense and tackle on defense. This was a desperate Dartmouth effort to stop the driving power of one of the great Cornell—really one of the great national teams of all time, inside and outside tackle.

And you know what happened!

Probably no Dartmouth player ever had a meaner job, and few, if any, have ever done one so beautifully. Nobody would want to take any glory from the inspired play of last year's Capt. Lou Young in that now historic contest.

That fighting son of the former Pennsylvania coach was magnificent, but in there with him, beside him, scattering, tearing and slaying, was this mighty refugee from the Minnesota gopher warrens. He's no gentle touch either in football or basketball. It's a case of old men and cripples get back of the ropes, when he goes. He likes 'em rough and he dishes it in kind. Don't get the idea our hero is any lah-de-dah, because, like Mr. Tunney, he's read a book.

He can suffer for a cause and keep his mouth shut, too.

The last month of last year, he kept on centering that football with perfect accuracy despite a pair of arms so bruised and banged that he couldn't lift them to the level of his shoulders. That was Blaik-Ellinger football, if you remember, and those Army coaches really drove.

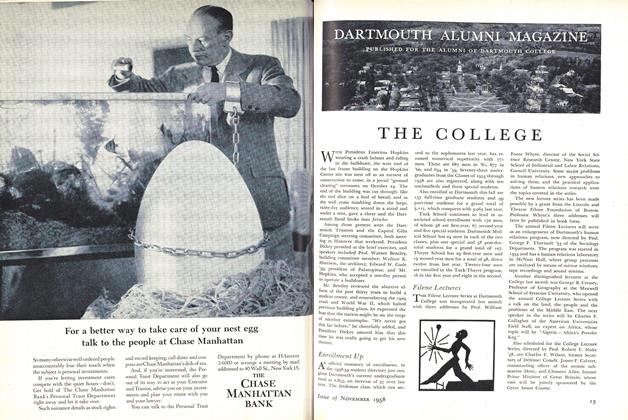

This year, he's had his own position at tackle, and, as this goes to the printer, his leadership has been inspirational, his play outstanding. It'll still be that while you're reading it too unless he's hit by a truck in the meantime.

The basketball story is just as brilliantour teams have been championship, and he's been sensational—but this is the foot ball season.

On the scholarship and honors side, he's: Phi Beta Kappa, Class President, Palaeopitus, Senior Fellow, Member of the famed Dartmouth Fire Squad, which is really a social distinction. His fraternity is Alpha Delt, his Senior Society, Casque & Gauntlet.

I shall not dwell upon the matter of the scholarship attainments, lest it seem too much like a shoat endeavoring to comment upon strawberries.

Except, for a couple of items. I've checked on the young man as a campus phenomenon and have discovered that his amazing class room record is the result of two things. The first is a fine, not necessarily a brilliant, mind. The next is a capacity for hitting real licks. The boy considers college an opportunity, not a privilege. He wants to make the most of it, and he has.

Every college day, football or not, he's up at six in the morning—probably a heritage of early life on the farm—and he gives the books a complete going over before the day's classes start. Supper over, he's at 'em again until ten or eleven. Intimates say he hasn't varied this routine ten times in three years. On football trips, he unsatchels his books as soon as the squad is settled on the train, and seldom takes his eyes off the pages until the point of destination.

Yet, for all this, he's not a grind. There's plenty of lift and bounce to him. He simply knows how to work, and is willing to.

It's probably futile in these times to ask a boy such as this what he "intends to do." Unfortunately, the decision may be taken out of his hands. But Pearson can tell you in a manly, modest, serious way what he'd like to do. He's obviously given it much serious thought, and although naturally hesitant about baring his soul to a stranger, and considerably embarrassed when he found I was talking with him with an idea of using his career as a subject of a hortatory article in this esteemed publication anyhow, he told me, with appropriate reserve, what he hopes with God's grace to make of it all.

He wants, he says, in his time, "to get into public life."

By that, he doesn't seem to mean politics. Neither does he seem to mean right away. He wants to start by going to law school. Then he thinks he'd like to go into school work, teaching at first, maybe, but aiming really at the executive end. He's done a lot of thinking about the educational system in this country. He's wondering if it couldn't be reshaped for the better at its veriest beginnings—in the grammar schools, high schools and preparatory courses in general.

He's not sure that this is it, but just, for instance, he wonders if instead of the present hodge-podge where every pupil studies everything and most of them get a little of much, and, only, occasionally, much of little, it wouldn't be better to start them specializing from the first.

If say, education were divided into three general classes: one as preparation for the expert study of business, one with foundation work in the various professions and the third as groundwork for military and naval careers. Wouldn't this, in a changing world, not only streamline education but provide this nation with better minds, better leadership?

Having the type of mind he owns himself, he hasn't taken that as infallible, just because he happened to think of it. He's merely set it up as something to start from, and he's asked sundry professors and others whose wisdom he respects to knock it apart and break it loose for him if they can. Some of them have hit it some lusty wallops. Then he's gone back and carefully considered their criticisms, taking the picture to pieces, fitting it back together with their suggestions or amputations and comparing it carefully with the original.

All this, of course, is nebulous, but it will serve to show you the sort of mind our football captain has, and some of what he does with it in his spare time.

CHANGES AHEAD

Possibly as the head of a school, this type or some other, he'd become part of a community, write books, be on committees, become identified with movements, and, as such, he'd move on "into public life." He thinks he'd like public life. One of the things he's enjoyed most about Dartmouth is organizational work. He thinks there's much to be done by real leaders, by intelligent public servants. He's orthodox American in his views, but he sees the whole world as changing, and although he doesn't say it just this way, what he means is we'll need—the world will need—men-the sort of men sung of in "Men of Dartmouth"—to straighten out the tangled mess if anything is to be saved.

He says he's gained confidence in his abilities for "organizational work" in his career thus far in Hanover.

"I've been able to get such little things as I was interested in done here," he says, "I don't see why the same might not apply with bigger things later, provided the bigger things are real and worth while."

I think you can place your bets now, gentlemen, if the world holds together sufficiently, and if nothing throws this young man from the track he's now on. And if I haven't sold you the finest undergraduate product Dartmouth has produced in our time, the fault's mine, not the product's. If there are any more Stub Pearsons in the vicinity of where you live and move and have your being, Brother, let's have 'em.

Not only Dartmouth, but America needs them now, and America is the hope of the world.

CHARLES M. (STUBBY) PEARSON, LEADER IN THE SENIOR CLASS

THIS IS THE SECOND in a series of descriptive articles about leaders in the undergraduate body whoare setting high standards in thebranches of student life in whichthey are prominent.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters From Bolte

November 1941 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917*

November 1941 By EUGENE D. TOWLER, DONALD BROOKS -

Article

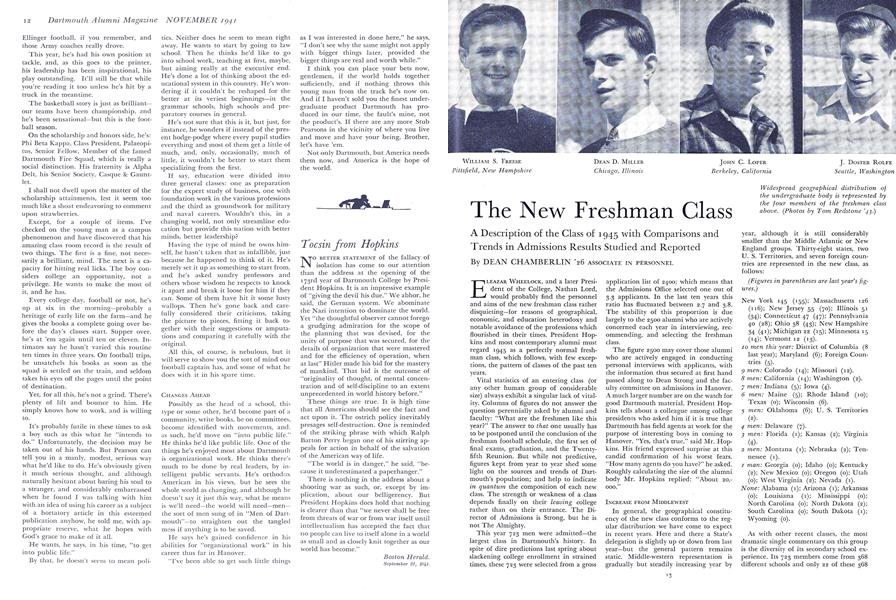

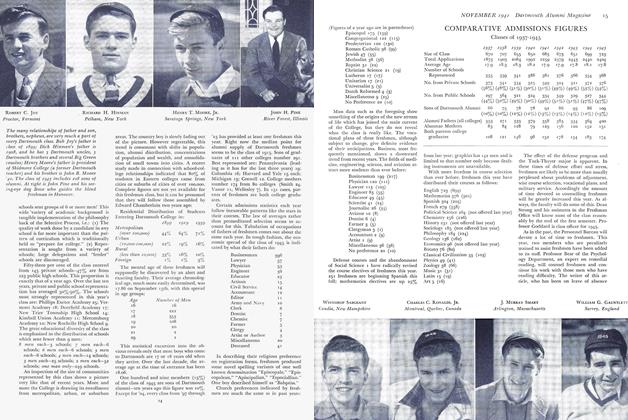

ArticleThe New Freshman Class

November 1941 By DEAN CHAMBERLIN '26 -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

November 1941 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1938*

November 1941 By CARL F. VONPECHMANN, J. CLARKE MATTIMORE, DAVID J. BRADLEY -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in New York

November 1941

BILL CUNNINGHAM '19

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS TO THE EDITOR

June 1935 -

Sports

SportsTHE NEBULOUS IVY LEAGUE

December 1937 By Bill Cunningham '19 -

Sports

SportsRIGOROUS DISCIPLINE

December 1937 By Bill Cunningham '19 -

Sports

SportsA MEMORABLE DINNER

December 1937 By Bill Cunningham '19 -

Books

BooksWINGS IN THE NIGHT

November 1938 By Bill Cunningham '19 -

Sports

SportsFootball Review

December 1938 By BILL CUNNINGHAM '19