With all of the very disjointed life on the campus there are slow awakenings to reality, and sharp, disturbing, agonizing realizations that being at Dartmouth is pretty much escape the way things are now. The Dartmouth reprinted Ralph Ingersoll's editorial "Are We Lenders or Fighters?" from PM, and more than one student silently stomached a strong dose of truth. Things like Ingersoll's editorial work silently, more silently and effectively than do the war movies about Tyrone Power joining Betty Grable and the RAF. If bombing scenes in the movies do happen to work a little spine-shifting, the pure hokum of a Hollywood all-out effort can be noisily denied. But you can't talk off the truth of a nation that hasn't decided whether it will lend or fight.

Just what will happen when enough of those minor, silent, powerful realizations work on the individual students to the extent that decisions are made can only be guessed at. There'll be more and more going to join the air forces, some going to Canada. This has been happening all along. But Dartmouth itself, that mass of undecided and disturbed and escapist boys and young men, won't find its own function as an institution unless the minor revolutions of its individuals become related to a major revolution in the College, changing purposelessness into strength and escape into effort. If those who decide that they must become a part of the war effort continue to leave College, and it is unavoidable that many of them do this, the College will continue as the repository of people who haven't yet made up their minds.

Meanwhile, there is the continuing struggle on the part of President Hopkins, some students and professors, and TheDartmouth to arouse group realization of the war and of the College's responsibility to educate men for places in that war and the world that will follow it. It has been a hopeless and thankless task so far, and with some justification. The decisions about what to do about the war must be made individually, there can be no answer in terms of the College as a whole until those decisions are made, and the only thing that can be hoped for is that the decisions will be made. Attempts at building mass war-time morale without first starting with individual morale must fail just as miserably at Dartmouth College as they do in the Nation as a whole; the big job for those who would make the College "an agency of helpfulness in a troubled world" is to see to it that the individuals in the institution are aware of the necessity for a decision and that they do not mark time in deciding.

The frailties of escape and indecision must not be allowed to continue self-perpetuating.

The Aegis has been sending around mimeographed postcards to members of the senior class advising them of appointments for their Aegis portraits. At fifteenminute intervals down on Main Street in George Higgins' studio members of the Class of 1942 sit nervously while Mr. Higgins tries to jolly them into ease so that their faces in the year-book won't look like dead haddock. And then there are the sheets of paper asking for name, extra-curricular activities, honors, and the like, to be turned in to the Aegis as soon as possible.

It's not a pleasant routine, being mugged and classified for the record, having to draw your four years of Dartmouth College into the machine process of a yearbook. It engenders a state of mind strangely and uncomfortably like that of my friend who argued that the doors of Dartmouth Hall are real; if I keep on being reminded that there are only a few more months left at Dartmouth I'm likely to begin feeling that the doors of Dartmouth Hall and other minor falsities about the place have a mellow, hazy reality. I'd had to get to the point of thinking Dartmouth College is so perfect and logical that I wouldn't know what door to go in to get to a classroom in Dartmouth Hall.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleSocial Idealism in College

December 1941 By ARTHUR E. JENSEN -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

December 1941 By Frank Hall '41 -

Article

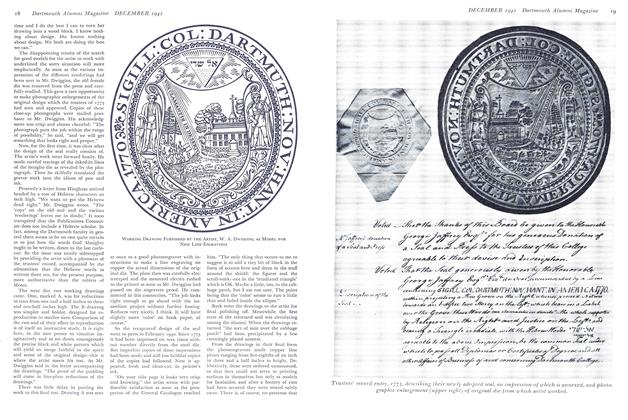

ArticleRediscovering the College Seal

December 1941 By RAY NASH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937*

December 1941 By DONALD C. MCKINLAY, ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912*

December 1941 By CONRAD E. SNOW, RICHARD C. PLUMER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919*

December 1941 By WINDSOR C. BATCHELDER, MAX A. NORTON

Craig Kuhn '42

-

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1941 By Craig Kuhn '42 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

October 1941 By Craig Kuhn '42 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1941 By Craig Kuhn '42 -

Article

ArticleINDIVIDUALS WEAKEN THE WHOLE

November 1941 By Craig Kuhn '42 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1941 By Craig Kuhn '42 -

Article

ArticleJUST A MATTER OF FRAILTY

December 1941 By Craig Kuhn '42

Article

-

Article

ArticleAlumni Award: John Adam Graf '58

September 1993 -

Article

ArticleBIG GREEN WIPES FIELD WITH ELIS

AUGUST 1929 By BILL CUNNINGHAM -

Article

ArticleWinter Carnival

February 1947 By C. E. W. -

Article

ArticleTrack

May 1956 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleNew York

January 1940 By Malcolm G. Rollins '11 -

Article

ArticleCOMMENCEMENT LIKE A CIRCUS

DECEMBER 1929 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett