Soldiers' Letters From Near and Far Are Added To Dartmouth's War Collection of Correspondence

A DESCRIPTION OF OFFICERTRAINING, USA, in which so manyalumni are now enrolled, is given in theqfollowing letter from Carl von Pechman,secretary-chairman of the class of 1938. Heis a first lieutenant now, instructing at theInfantry School, Ft. Benning, Ga.

MAYBE I FELT LIKE a lot of other egotistical people did. "They'll never draft me." I guess too I'm one of the crowd that's criticized now, for not having been aware of the gravity of the situation. I did think it was a shame we didn't do something, but I didn't know what.

When the President's invitation did arrive, it caught me completely by surprise, two days' notice to be at Fort Dix, and me in Indianapolis. Everyone had told me I couldn't possibly pass the physical. Somebody had told me to report in as disreputable a costume as I could muster. Then the jokers who hand out clothes would take pity on me, and give me a uniform that would approximate the shape of my body. The family was in hysterics watching me get ready, and I must say it was a little funny when I showed up at the draft board.

Everyone else was dressed to kill, and it looked as if we were all off to Boston for a week-end. I survived that, and five days of Dix, snow, a cold chow line, and outdoor latrines, before I hit the rails for Fort Jackson—me and the fattest man in the army in the same berth. I hadn't been able to get to a phone before I left, to tell Mother the news, and at 11:00 that night she took it on herself to call me instead. That was my first chance to unveil the scorn of a Ist Sergeant. From the very first day, though, I had a good time. We had a good bunch of boys in my tent, and college and my job had gotten me used to doing different things.

The army makes you feel younger. Kid non-coms bossed us around, kid lieutenants too, and it does something to your confidence to have to accept everything they said and did. You don't feel like a tycoon of business to have some corporal from West Virginia tell you to wash the bowls.

Fort Jackson was good, good and hot too. I'd never met people like my bunkmates. A Polish stevedore and a Spanish truck-driver never meant anything to me, and they're fine people after you get to know them. I regretted for a while not having taken some R.O.T.C. work, but if I had, I don't think I'd have known the army. I was sorry to leave them.

They gave me a pair of gold bars when I left. They were more optimistic than I was. My corporal wanted to pay me a nickel to polish his shoes. I had him wash my leggings in trade, instead. I knew some people in Columbia, S. C., so my stay was pleasant. I hopped into my civilian clothes almost every night, and was in town. A few months had flown by, and I'd put in my application for Officer Candidate School. I was a Corporal then, and life was easy. I was recommended for Sergeant, but was vetoed because I was too polite to the men. I was tipped off, and for a month swore like a trooper, yelled at everyone, and lo and behold I was a sergeant. Then I went back to form, and everyone was satisfied. My men liked to do things for me, I think. I never had the trouble others did. See the making of a "good" soldier—getting cocky. Funny things pleased me then—having some thug say I was a good soldier, having my squads complimented.

The Infantry School contains instructional teams in all weapons, tactics, logistics, administration, etc. We have three infantry regiments to help, along with a tank battalion, some engineers, etc., with demonstrations, and who act as the school troops. The three months' course given to officer candidates is the same as is given to commissioned officers who come for refresher courses, and in addition we have short courses for advanced training of higher officers. I teach mechanical training and technique of fire of the mortars, which takes up three days of each student's time, and I like doing it.

I was in the sixth O.C. class. Since then we've graduated 8,000 2nd Lieutenants, and by this time next year we'll have put through some tens of thousands. Our associates are superior as instructors, and there's not much play with mediocrity. The average soldier, I think, has decided the army is poorly run. The school would change his opinion. If it is poorly run, it's in the misapplication of theories taught here. It's a busy three months for a student. He spends six to seven weeks on weapons, the rifle, automatic rifle, machine gun, mortar, 37-mm, bayonet and hand grenade. The remainder of his course is in tactics, supply, and things of a more general nature. Theoretically, any graduate is presumed capable of performing any function of subordinate command in the infantry, and most of them are assigned to command platoons. We lay great stress on instructional methods, since a platoon leader is a teacher as well as a leader.

Initially, the greatest percentage of graduates were sent to replacement centers as instructors. Now they go to the new divisions, only a small portion going overseas immediately. A small group from each class is absorbed into the paratroops.

There is a tendency to remain static, but there's small chance of it with all the reorganization taking place, new weapons, and new problems of tactics. We may be a bit behind, but we try not to think so.

IT'S A FULL DAY

A typical student's day starts at 5:45, when he has time to shower, shave, and perhaps make his bed before breakfast at 6:30. After breakfast he dusts, shines and prepares his equipment and barrack for inspection. Inspections are made during the day and delinquencies are noted on a "gig" sheet. It's good training in discipline, the army's general thought being that proficiency in small things extends to the larger. It does if you don't get too involved in detail. Anywhere from ten to twenty per cent of each class is dropped before graduation. At 7:30 the company falls out under command of its students, with regular company officers as observers. Depending on the location of their class area the com- pany either trucks it, trains it, or hoofs it to work. Classes go on all day including Saturday (Sunday in the offing), with ten minute "breaks" each hour. Lunch is either in the field, cafeteria style, or at home. There's a study hall at night, com- pulsory for an hour, time for a beer, a little chatter, and cleaning up. Lights are out at 10:00, and bed check at 11:00.

Our appointments to the faculty are presumably for a year. We either live in town with our wives, or in officers' quarters on the post. It's not a hard life, by any stretch of the imagination; we've got a good club, plenty of attractive people, a golf course and swimming pool. All they ask is we know our material, present it clearly and with enthusiasm, and conform to the schedules. Everything runs like clockwork. The schedules are masterpieces of precision. We get a little itchy for troop duty, every so often, and then when we realize how lucky we are, we thank Jehovah and the President for the Infantry School. Our big concern is how we'll convince our children we had anything to do with the conduct of the war. We'll change our tune when our year is up.

I don't know what I've gotten out of the army—a great deal more self-confidence, a chance to meet so many different kinds of people, a feeling of doing something useful, and a greater tendency to let other people make decisions for me. It's only when an officer is isolated from his superiors that he can act entirely on his own initiative, generally speaking. We're younger at the game. That's as it should be.

An Officer's Job

THE FOLLOWING LETTER was written athis "task force" headquarters by a commanding officer who was a junior officer inthe World War, and, from its close, kept uphis service in the National Guard untilcalled into Federal service in September,1940. He is Lt. Col. Henry G. Fowler '17,who is now in command of the artillery atan important post in the Southwest Pacific.He has attempted to interpret the attitudeof the American soldier toward the officersunder whom he serves and toward thehome front, and to suggest to officers intraining where they should put the emphasis in their personal training and intheir relations with those under their command.

A few thank God only a few officers still come out to scenes of action, or possible action, imbued with the idea that the morale of men under them depends upon the entertainment, or distractions, that can be provided for them. Nothing could be further from the truth. The American soldier comes into the field with one sole idea uppermost, namely, to do the job thoroughly and as quickly as possible so that he can get back home to the distractions of his personal choice.

His morale depends entirely on his confidence in his leaders. He asks only two things:

First, That the work assigned to him be essential to the main effort—no boondoggling and that he be told clearly what is expected of him.

Second, That all the creature comforts practical in the situation be provided him.

Perhaps unconsciously he asks a third, that his officers prepare themselves for the problem in hand and plan assiduously to insure that his efforts be not wasted. His greatest strength as a soldier lies in his capacity to see quickly what is needed, and in his willingness to do what he thinks right without regard for his personal welfare. It is that latter trait that makes heroes of men who will later quake with fear at what they have done—or may even quake in the doing, but go ahead. In his leaders, he expects the same insight and mutative in a greater degree. If they seem have it, nothing will shake his morale. He will shirk only when those above and about him appear to be muddled, lazy or timid.

In the same way, he expects those at home to "put out" to spare no pains to give him the means to win his fight. He may even forget that they are getting time and a half for overtime, and that they are enjoying most of the things denied him—at least until he gets home—provided that he can see guns, ammunition, planes and replacements coming out in a rising flood.

So far, Uncle Sam is doing all right in most places. The men who fought the good fight in the Philippines may now be a bit downhearted that the flood could not reach them in time. But most soldiers are willing to forgive the late start if a few more speed records are broken. They'll eat the dried cabbage, ham loaf and chile without end because they are doing enough to be damned hungry if only the planes and ships come sliding in with men and materials and mail. And right now the tide appears to be rising, however slowly.

So, when your outfit is ordered overseas, don't be too concerned about how much post, camp and station equipment you can sneak aboard ship—unless it will help win battles. Don't let the lads load up a lot of loot and luxury. Just be certain that you know what YOU are going to do when you get off the ship, and that you have prepared yourself to LEAD your troops without cajoling them. Morale won't worry you then.

Aviation Cadet, V-5, USNR

SOMETHING OF THE SCHEDULE and interests of men in training for Naval Aviation is carried in the following letter fromCadet A. H. Rowan Jr. '44 located at theUSNR pre-flight training school at ChapelHill, N. C. We are indebted to his father,Mr. A. H. Rowan of New York City, forgiving us the letter to him which follows:

Well, so far so good. I am still alive and kicking after the first week of the most strenuous training program ever given to anyone in the history of the United States.

Thanks so much for sending me the radio. You just don't know how wonderful it is to come back into the room after a gruelling morning and to be able to listen to some music and relax. Right now I am writing this letter as I listen to Bethoven's Sixth Symphony in the regular Sunday afternoon Concert. In less than fifteen minutes I am going to try and get Shostakovich's Seventh, and I shall be very disappointed if I fail.

What I meant by the statement that you won't be able to recognize me is that I am liable to be heavier, tougher and a rugged looking individual. As our Commanding Officer so ably put it in a speech the other night, "By the end of the three months' training here at Chapel Hill you will all be the toughest, roughest, meanest, smartest bunch of fighters in the world" and I am willing to believe him. Take a look at my regular week-day schedule: 5:30' A.M. Reveille 6:00 March to Breakfast 7:10-8:00 Boxing Class 8:00-9.10 Football in full uniformspads, etc. (Just got the Seventh Symphony very well!) 9:30 First Aid Class 10:30-11:40 Infantry Drill 12:05 March to Lunch 1:00- 3:15 Classes in Math., Naval Customs, and Aircraft Nomenclature and Recognition, a strictly secret course 3:30- 5:15 Soccer practice and game 6:00 March to Supper 7:30 Call to rooms for study (or letter writing!) 9:30 Taps and lights out

On Wednesdays instead of First Aid and Infantry Drill we have a 6-7 mile "hike" and, on Saturdays we have a 12-16 mile "hike" which lasts from 7:10-11:30. This last Saturday we went 12 miles at a really fast pace. The sports we take are changed every two weeks, and include such things as Labor, Wrestling, Swimming, Hand to Hand Fighting, Volleyball, Basketball, Track, etc. All in all, you see, we get a workout each day. Our only real free time occurs when we get "town liberty" on Saturdays from noon until 11:00 P.M. and on Sundays from noon until 6:00 P.M. Even on this liberty we are not allowed to leave the town limits of Chapel Hill.

The heat down here is almost unbearable. The heat never seems to let down for one moment, and we occasionally get thunder showers which last for about half an hour. Our clothes are always just wringing with sweat. To counteract this loss of water, and loss of salt balance we have to eat a teaspoonful of salt before each meal to prevent dehydration and heat exhaustion. From local reports down here, they don't seem to get much winter because there is a tradition in the University that whenever it snows there is a holiday I think they ought to start that up at Dartmouth!

Yesterday, by the way, I had my second typhoid injection and my arm is a little stiff as a result. I have heard that before we get out of here we will have been inoculated against malaria and spotted fever as well. Someone was asked what they thought of the Pre-Flight School and his answer was "I think that if I live through it, I'll be able to fly without wings." Maybe he's right. Anyway I'm convinced that this training is a good thing and very necessary because of the terrific strain imposed on the pilots of the modern airplane. He must be a man who is tough and well conditioned, and that is what this training does for us.

P.S. The Seventh Symphony in my estimation is a masterpiece, a parallel to Beethoven's Fifth, and I hope you were inspired as much as I was. His orchestrations of the strings are unparalleled and the whole piece is the work of a genius.

From the Pacific

GEOGRAPHY IS MAKING a vivid, new impression on Americans, whether experienced at first hand or through lettershome and newspaper reports. PFC BobWebb '34, formerly with the Boston Transcript, writes from New Caledonia, U. S.Army:

Enclosed you will find a check tor ten as my contribution to the Alumni Fund. I can spare this like I can spare ten teeth but apparently the College is up against it and I'm darned sure I want to help. By the way, the ALUMNI MAGAZINE comes through and I read its enjoyable contents from cover to cover. Few Dartmouth men here except Dave Brinkman '38, Tom Dunlevy, Col. Howard Fuller '15 and your correspondent.

The sea voyage out here was tough. We hung around the equator much of the way and under blackout conditions, portholes had to be shut. Food was pretty bad. Most o£ the boys lost weight. Now, though, we're putting some of it back.

Melbourne, where I was fortunate enough to spend 5 days, is a beautiful, modern cityexcellent transportation, good buildings, ships, etc. A great surprise to me. Most of the 7 million people in Australia live in either Melbourne or Sydney as both cities go over a million. We were about the first American troops in Australia and they gave us a genuine welcome. The Aussies really look up to the Americans and seem to regard America as a sort of Utopia. Lots of the Yanks like Australia so well I wouldn't wonder if a great many of them settled there after the war. A great country, Australia, and a great opportunity for an American who can break the home ties.

New Caledonia is also a young country. Captain Cook discovered it in 1774 although nothing much was done until 1853 when the French decided to send their public enemies here. A penal colony from that time until 1893, New Caledonia still bears the scars of the criminal regime. A few old libres (freed convicts) are still stumbling around, but their number is only a few hundred.

In the early days (before 1853) there was cannibalism about. On one occasion, 12 sailors went too far afield and were placed on the menu for their trouble. Descendants of these natives (Canaques or Kanakas) have become civilized and are now quite friendly. The native blacks are numerous. Next in line are the indentured Javanese who come to the island to work for 5-year periods, then are returned. Usually they work in the nickel mines or on cattle stations. The Javanese women are very petite, usually about 4' 9" tall. They go barefooted, wear bright colors, and have a sling over their shoulders for provisions or babies.

Climate here is great—hot all day (even in winter) and cool at night. Greatest drawback are great swarms of mosquitoes which flourish from November to May, and the rest of the time as far as I can see. Island is 250 miles by 30 miles, has a high chain of mountains up the middle, is virtually surrounded by a reef and boasts one road from tip to tip.

Please give my best to all Hanover friends particularly McCarter, Hoehn, Sayre, Widmayer and Dickerson. Enclosed a paper and some stamps for a youngster, perhaps your own.

"See More Clearly"

STATIONED IN THE PACIFIC, Ensign Donald C. McKinlay '37, contributesthoughtfully to our Dartmouth War Letters in the following abstracts from a message recently received:

Every once in a while we all feel a bit lonesome, homesick, and hopeful for a transfer or "something new"; we miss our wives and families and friends; we miss New Hampshire's cool calm like everything.

But it's great just to be alive and more and more I appreciate that one fact alone. It isn't that we're afraid to die, or even thinking about it, but rather we see more clearly the real things in life and I know that I for one have every hope of a world at peace—to think otherwise is to give up—to take away any purpose that there is in the war.

The war has given us a chance to look back and look ahead at the same time. It has taken us away from the many beautiful things which we had come to take for granted, and which I believe we didn't fully appreciate.

I know there will be more Dartmouths who will be "whole men" after the war, than there were before. Money, wealth, fame, and ambition dwindle into tiny bits when a country or a person is fighting for its or his or her life. They dwindle when a person falls sick, when a person's husband or wife, or children are killed or even when a young couple is separated due to the rules and needs of war. As yet I haven't had time to read the June MAGAZINE completely but everything I found to date has been encouraging and inspiring. The men who speak through its pages sincerely believe what they say. There isn't a selfish or cowardly word in it. They speak still of ideals—and the great need for keeping them before us—not to be too "practical" in all our thinking.

My wife, Barbara, as I may have told you, is working under Basil Winslow '20, at the Pacific Tel. & Tel. Cos. in San Francisco. The meeting and hiring was pure coincidence, honest! She recently met Joan Stern, the wife of Charles Stern '36, who was killed on December 7, at Honolulu. Barbara says of Joan:

"She went to Pearl Harbor a year ago to marry Charles and they were in the Islands on the 7th. She came back after she heard of his death and is now working here. Charles must have been a wonderful person. He wanted to be the first Dartmouth man to get into the middle of it and Joan says he would be happy if he knew that he was the first Dartmouth man to give his life for the United States. From his letters, of which Joan has read me parts, he had a very optimistic outlook and had faith in our cause."

Started at the Bottom

OUR ADMIRATION AND RESPECT go inlarge measure to men in uniform whostart at the bottom. John French '30,former editor of The Dartmouth androommate for four years in Hanover ofNelson A. Rockefeller'30, says of his Armycareer, since enlisting as a private:

In view of your interest in alumni in uniform, you may be interested in knowing where I've wound up.

I was inducted in New York on March 26 and sent to Fort Upton, on Long Island. After a few days there getting equipped and being inoculated, etc. I was shipped to Fort Jackson and have been here 3 months.

Perhaps I can give you some idea of the pace of our training by saying that while I have never been fat, I now weigh 16 pounds less than when I landed here. They are dishing it out to us just as fast as we can take it. For an old man like me, it's quite an experience.

The other day, for example, we had a platoon attack problem that took us through about 200 yards of tropical swamp knee-deep and even waist-deep in muck. Three water moccasins were discovered in the process. We were told afterwards that the idea was to show us that what the British thought the Japs couldn't do in Malaya was in fact perfectly feasible.

We also have an obstacle course that we go through about twice a week—with pack and rifle. This involves climbing a 20-ft. rope, scaling a 13-foot wall, swinging over two pools on horizontal ladders, jumping over several sets of hurdles, wriggling through a pipe, climbing in and out of trenches, etc. It's no wonder that my pants are a little large.

The boys I am with are a fairly homogeneous lot just about 97% Polish, with a couple of scrappy Irishmen, two Chinamen named Wong and Ngo, and myself. Actually there are quite a few really outstanding people and I suppose the whole company would be considered as a typical American crowd. I've certainly been brought into contact with types of people whom I wouldn't have met anywhere else, and for me it has been a most helpful experience. With surprisingly few exceptions, these boys are o.k.

The only thing that worries me at all is the absence of any clear idea as to what the war is all about. By many, Japan is regarded as the chief enemy, simply because of the attack on Pearl Harbor, and there is an inadequate realization of the threat of Naziism. I'm sure our boys will do what they're told when they get on the firing line, but I can't help feeling that the soldier who knows what he's fighting for will do a better job than the one who doesn't. Perhaps this situation will straighten itself out as we go along.

After a month as buck private, when I learned how to peel potatoes and clean garbage pails, I was made a corporal, acting as a squad leader, and about June 1, I became platoon guide with the rank of sergeant. I have put in an application for officer's school which I should hear from in a few weeks. However, whether I make it or not, I am convinced that I did the right thing in starting at the bottom.

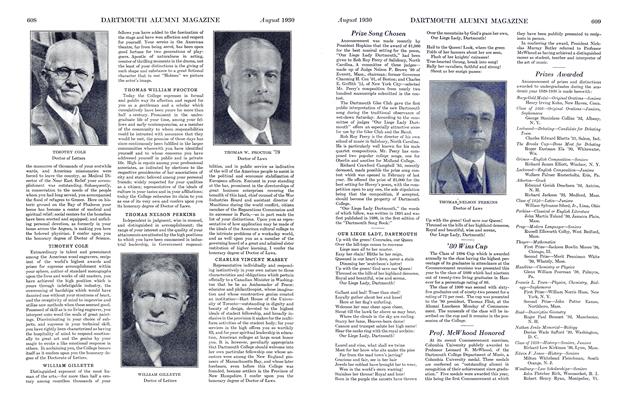

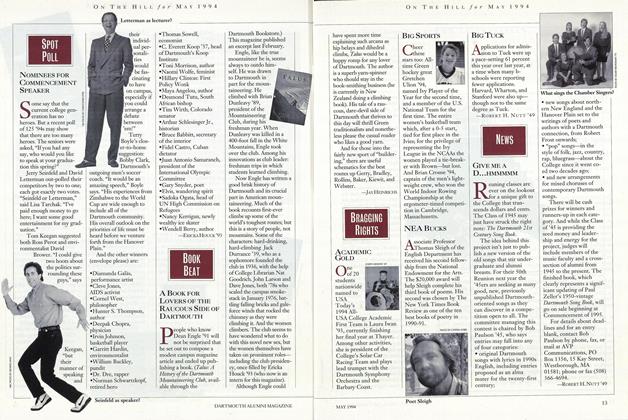

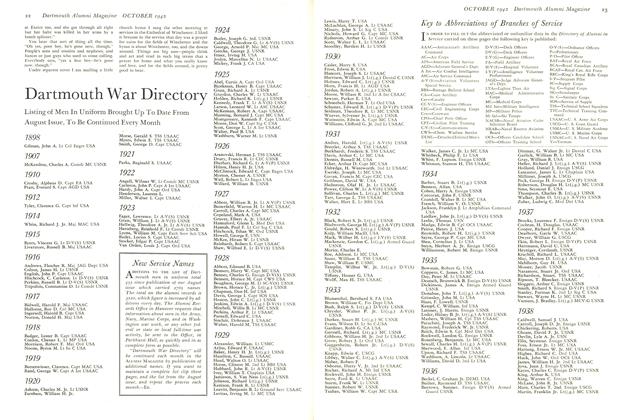

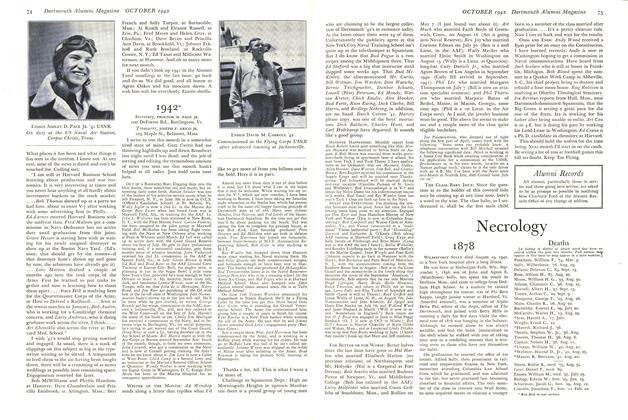

DARTMOUTH MEN IN NAVY, AND IN HANOVER TOO Shown above are alumni trainees in the Naval Training School at Dartmouth who were mem-bers of the first i?idoctrination class that graduated September 8. They are, front row, left to right: Lt. Earl E. Krogstad '27, Lt. John G. Cook '2B, Lt. George C. Forman '2l, Ens. Oliver A.Quayle 111 '42, Ens. Lewis K. Johnstone '4l, Ens. Roger Sands '42, Ens. Raymond W. WattlesJr. '42. Second row: Lt. (jg) William S. Hog'e '27, Ens. F. Whitney Rideout '37, Lt. (jg) David T.Hedges '34, Ens. Lewis J. Moorman '3B, Ens. Warner B. Bishop '4l, Ens. Benjamin H. Bacon '4O,Ens. Richard D. Hill '4l. Third row: Ens. Howard P. Chivers '39, Lt. (jg) Edgar S. Everhart '35,Lt. (jg) Alfred M. Seaber '29, Ens. Charles R. Hulsart '34, Ens. George W. McCleary '36, Ens. Vin-cent R. Else '4l. Not in picture: Lt. (jg) Robert T. Bates '32, Lt. (jg) Richard T. Clarke '32,Lt. (jg) Arthur S. Hyman '3l.

ENSIGN CHARLES M. STERN JR. '36 USNR Killed in action at Pearl Harbor, December7, 1941. Ensign Stern was the first Dart-mouth man to lose his life in active service.

IT is OUR PRIVILEGE to pass on to the 14, 500 Dartmouth men and families whoare readers of this magazine some ofthe letters, in whole or part, that are beingreceived in Hanover from alumni in theService. We are hopeful that many othermen will take the time and trouble to writedescriptions of their experiences in training and action. The letters will be added tothe Baker Library Dartmouth War Recordand may also be published in future issuesof the ALUMNI MAGAZINE.—ED.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters from Tom Braden '40

October 1942 -

Article

ArticlePresident's Address Opens 174th College Year

October 1942 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth War Directory

October 1942 -

Article

ArticlePay-As-You-Go Taxation

October 1942 By BEARDSLEY RUML '15 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

October 1942 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942*

October 1942 By PROCTOR H. PAGE JR., JOSEPH F. ARICO JR.