It would be difficult to find a parallel for the amazing change of front on the part of undergraduate opinion throughout the United States with respect to the matter of our entering the war. Through the past quarter century the trend of undergraduate thought was overwhelmingly toward the exaltation of peace—at times reaching the limit of demanding peace at any conceivable price and hinting that no war in any circumstances could be justified. Here and there flaming apostles of pacifism could be found demanding that college youth lead the way in taking a solemn oath never in any conditions to take up arms.

A milder version of this demand specified actual and physical invasion of American territory as the one condition precedent to enlisting as a soldier. Two years ago no one would have dared to predict the extraordinary revulsion of opinion which a glance at any college campus today will reveal as a fait accompli. Two years ago one might find anywhere hundreds of earnest young men ready to affirm, in large part because of what their teachers had taught them, that the first World War was a sordid business instigated by human greed for the defense of vested interests, and that the second World War, then just aborning, would be like unto the first. Try to find a trace of that today!

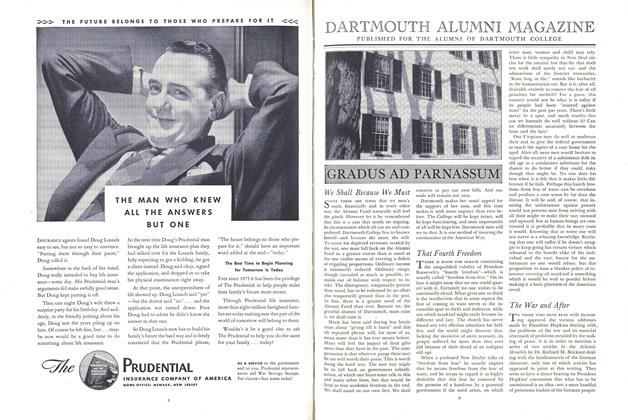

Among the first—perhaps the very first- of all the voices raised to demand active and whole-hearted intervention in the struggle that was threatening to engulf and enslave the world was heard here in Hanover, on the Dartmouth campus, from a man who immediately after graduation sought active service among the belligerents, thereby proving that his was no mere lipservice of an ideal. In the columns of TheDartmouth for April 24, 1941, appeared a passionate declaration of faith in the form of an open letter to the President of the United States, beginning "Now we have waited long enough" and condemning the namby-pamby doctrine of giving "all aid short of war." It was penned by Charles G. Bolte of the class of 1941 and the demand was that we stop the spineless shillyshallying by sending "American pilots, mechanics, sailors and soldiers to fight wherever they are needed." It seemed to him shameful to mince words, to hang back still hoping for business as usual, to play the ostrich by refusing to see what every one must see if he looked, to aspire to save our own skins by "the craven phrase 'short of war.' "

When Bolte wrote that he said what it was not fashionable to say. He voiced a creed that college students for almost 25 years had reprobated and condemned. He followed it up by enlisting that same summer in the King's Royal Rifles—a regiment directly descended from Rogers' Rangersand by going with that regiment to the most active kind of active service. Five Dartmouth men altogether are serving in that same outfit, if still fortunate enough to be alive. Thousands of others are on the point of following where they have led— not whining, not whimpering, not selfpitying, but eager to bear their full part in helping to save the world from a reversion to barbarism.

We feel that a word is due the protagonists of the brave new attitude of mind, such as Charles Bolte of the class of '41, who were courageous and far-sighted enough to sound the clarion call and awaken those that slept. (A report of 2nd Lt. Bolte's wounds in the Battle of Egypt, necessitating amputation of a foot, is carried in College News this month.)

NEW NAVY SEAL The U. S. Naval Training School at Dartmouth College has adopted the above insignia as a non-official symbol, indicatingits close relationships with the College.Artist of the Seal is Ens. James V. Bartlett,Annapolis '41, assistant to the executive officer of the Naval School in Hanover.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHanover's First Aid Maestro

December 1942 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

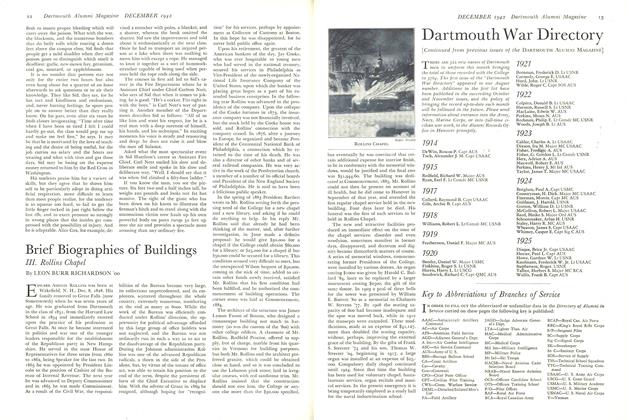

ArticleDartmouth War Directory

December 1942 -

Article

ArticleThe Five Maries

December 1942 By WILLIAM CARROLL HILL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

December 1942 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935*

December 1942 By JOHN D. GILCHRIST JR., BOBB CHANEY -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

December 1942 By Elmer Stevens JR. '43