THERE IS A POSSIBILITY—one wishes it could be called a probability—that by the time these lines are in print the war will be at least partly over. Not, however, because it will simplify the problems of the colleges when it ends. For most, one fears, it will amplify them—and what's more will pose problems to the solution of which there is no clue in the way of precedent. Every past war has entailed a strain on the American colleges, but never to the extent involved in the present conflict. Never before, to any such degree, has the federal government intervened in the course of a war by taking over college facilities and paying the bills. Necessarily there will come a period of readjustment during which the problems will be partly educational and partly financial.

While it has been using the plants and staffs of the colleges, the government has been bearing the cost of its use of such facilities and the net result has been that operating costs have been met. The number of students on the ground has, in Dartmouth's case, been substantially equal to the college population in times of peace. A sudden ending of the war would lead to an equally sudden dislocation, through the immediate diminution of the numbers maintained in naval and military units and a comparable decrease in the payments made.

Naturally the colleges hope, and reasonably expect, to revive conditions as they stood prior to the war in the matter of numbers of students under instruction— which in Dartmouth's case means about 2400 enrolled. But no one can tell how rapidly this return to the normal peacetime population will be accomplished. Meantime it is desirable to see that the plant itself shall not deteriorate and that the faculty shall be maintained in being, fully ready to meet the revival of full normal conditions when that comes. It is almost certain that there will be a considerable lag, during which the plant and its operating force will exceed the requirement, and it is to take care of that interval that the college has laid by a "reconversion fund" which will cushion the shock.

Various elements need to be considered in this matter of recovery, and as to none of them can any one be very sure. How many of the younger men, whose education has been rudely interrupted by the war, will seek to return to the colleges and take up their courses where they were laid down? How many will be financially capable of doing it? To what extent will the project for federal aid in such matters suffice? More vitally still, perhaps, will the economic situation of parents support the normal number of applications for admission in the case of young people, not in the war, who are just now arriving at college age? These are things that only time and experience can deal with. Economic changes seem fairly certain, for the cessation of the war will not relieve altogether the pressures. We shall not be paying out so much for fighting, but we shall be spending a great deal of money for other things, such as bonuses, rehabilitation, and the growing costs of debt-service, not to mention that social reform which the war has partially interrupted. One may be pardoned a bit of disquiet as to the ability of ordinary families to finance collegiate education for their children. For a time, at least, it would seem probable that applicants will be somewhat less numerous than they used to be in pre-war days.

The important thing, however, is to provide as best we may to weather the intervening period between the end of the war and the full return of normality. The Alumni Fund will be an important element in furnishing an adequate answer.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE THAYER SCHOOL

February 1945 By PROF. WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '28, -

Article

ArticleA CIVIL WAR STUDENT

February 1945 By EDWARD CHASE KIRKLAND '16 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

February 1945 By H. F. W. -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Casualties

February 1945 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

February 1945 By JOHN A. KOSLOWSKI, WILLIAM T. MAECK

P. S. M.

-

Article

ArticleEducation for the Submerged

December 1942 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleWhy Pick on Friday?

January 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleWorth Doing Well

November 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleAn Item To Budget

December 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleWhat Are the Liberal Arts?

November 1944 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleLet Them Eat Spinach?

August 1945 By P. S. M.

Article

-

Article

ArticleClub President of the Year

NOVEMBER 1962 -

Article

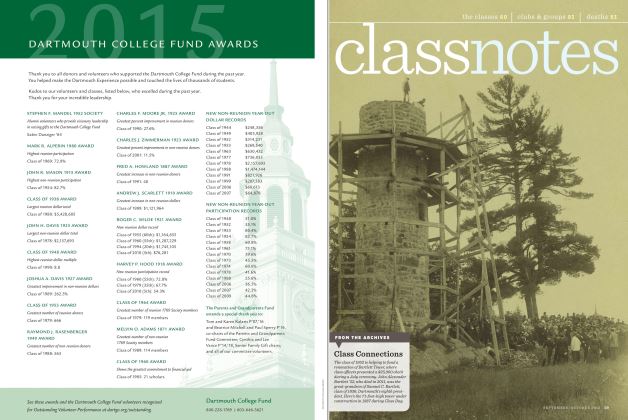

ArticleConvocation speaker to open Hood dedication

SEPTEMBER 1985 -

Article

ArticleVoici les Chevaliers sur le Bateua

December 1989 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse

May/June 2007 -

Article

ArticleClass Connections

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2015 -

Article

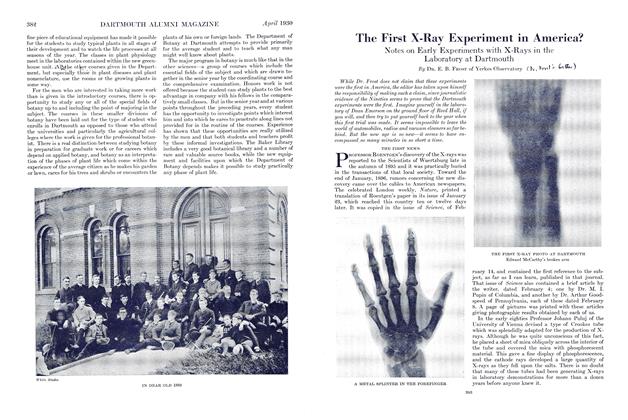

ArticleThe First X-Ray Experiment in America?

APRIL 1930 By DR. E. B. FROST of Yerkes Observatory (Dr. fnrt's )