By Ramon Guthrie. New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1968.132 pp. $4.95.

Ramon Guthrie is the only first-rate comic poet writing in English on either side of a shrunken Atlantic. The term "comic poet" is not meant to place him among the humorists. I have in mind Aristophanes and Villon, and in my ears, from him as from them, a ribald laughter that reechoes through air rarefied by wisdom and suffering. Byron gave voice to it at times, as did Edwin Arlington Robinson in the tenderly raffish impulse that uttered "Mr. Flood's Party." But Guthrie, with his fantastic range, is a larger and more steadily successful poet than either of these; he never twists open the spigot and lets it gush, as they did in so much of their verse. His work is pared to unobtrusive precision in every phrase.

And the richness of imagination! "Stalled Meteor." Who but Guthrie would ever think of a stalled meteor, in any connection? But this is Part III of "Suite by the River," one of the tenderest love poems I know; it deals with the ways of numbering time, that will close all our joys, and with the desperate void which anticipates a parting that must occur. The stalled meteor, viewed on its own in relative time-space for 18 lines, suddenly is as distant as you and I lying in the caduceus orbit of each others' arms impenetrably clothed in our reciprocal nakedness Sluiced by oncoming dawnyou are farand nearshaped ivory whose glosslint of sleep a moment yet obscures.

So ends the book's first poem. It has the special Guthrie magic of entire simplicity upon a first casual reading, with an echo from depths to be perceived upon a return. It is addressed to Mélusine. Why? As in the legend itself of that elusive thirteenth century lady, "natural in spite of a free use of the marvelous," the poem's surface naturalness opens to reveal marvelous evocations like those that hover and shift behind a tapestry.

This is even more true of "Pattern for a Brocade Shroud," in which the poet confronts the rigmaroles of death and interment, stipulating for his own case a simplicity that he knows will be denied him. The confrontation with death always has been this comic poet's central subject. Prior to "Shroud" the ultimate statement seemed to be "Dead, How to Become It," in Graffiti (1959), with its heartbreaking categories:

there are also young men's deaths like a puppy's lunge parting a frayed leash.

An immense, curious learning shuttles through Asbestos Phoenix — of brawlers who happened to be Breton saints, unorthodox cosmogonies, modern art, classical legend, baroque music - interwoven with recollections of the poet's tough fellow-workers in Wall Street or on the Brooklyn docks, all brought into a kind of wild relevance. And there are the blistering political poems, "Homage to John Foster Dulles," "Some of Us Must Remember." Those who read the latter when it came out a year ago in a periodical should watch for something new near the ending; Straight-faced, an Army major explained, "It became necessary to destroy this town to save it." In the days when soldiers still were soldiers, he would have achieved a twisted grin of sorts and set his pistol to his temple, leaving a note requesting he be spared burial with military honors.

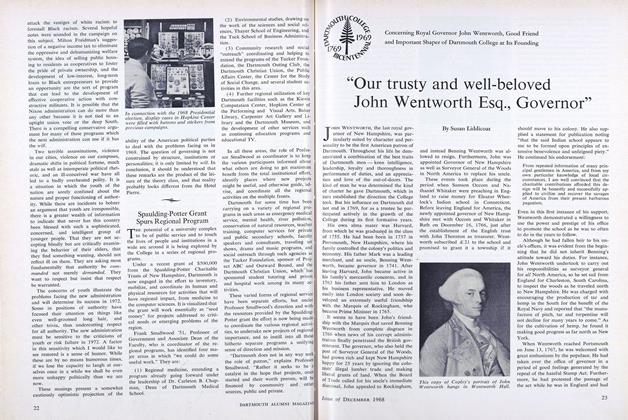

Soon after "Shroud" was first printed in the Carleton Miscellany, the French critic Laurette Véza wrote an analysis of it for Etudes Anglaises in which she said Guthrie's work was "un auto-portrait constamment retouché." An invitation followed to read his poems in English at the Sorbonne and other French universities. His own country has been less perceptive, partly because he has never played the academicpoetic game. For more than three decades he was an utterly committed teacher of French literature; he reread the whole of Proust every year to make a term course always new. His young books of the twenties were followed by works of scholarship until Graffiti reminded us that the center of great teaching is poetry. With his retirement five years ago from formal classwork the full rush began of the poetry that always was there. Asbestos Phoenix presents only a third of Guthrie's work of the sixties. Another book, Maximum Security Ward, is about ready. When the winnowing is done, of mere critics as well as of poets, I want to stand upon the judgment that the finest and fullest reach of American poetry in the sixties can be best perceived in these two books.

Portrait of poet Ramon Guthrie, paintedlast year by Nan Lewis of Thetford, Vt.

Novelist and poet, Mr. Laing is Professorof Belles Lettres, Emeritus.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"Our trusty and well-beloved John Wentworth Esq., Governor"

December 1968 By Susan Liddicoat -

Feature

FeatureOf Peaceful Men and Violent Ideas

December 1968 By DEAN THADDEUS SEYMOUR -

Feature

FeaturePolitical Year 1968: A Reprise

December 1968 By EDWARD W. GUDE '59, INSTRUCTOR IN GOVERNMENT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

December 1968 By STANLEY H. SILVERMAN, EDWARD S. BROWN JR. -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

December 1968 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

December 1968 By RICHARD K. MONTGOMERY, C. HALL COLTON

ALEXANDER LAING '25

-

Books

BooksHAWAII WITH SYDNEY A. CLARK,

June 1939 By Alexander Laing '25 -

Books

BooksTHE KING'S STILTS

January 1940 By Alexander Laing '25 -

Books

BooksHORTON HATCHES THE EGG

December 1940 By Alexander Laing '25 -

Books

BooksA MIRROR FOR AMERICANS. LIFE AND MANNERS IN THE UNITED STATES 1790-1870 AS RECORDED BY AMERICAN TRAVELERS.

January 1953 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksROBERT SALMON: PAINTER OF SHIP & SHORE.

DECEMBER 1971 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksFITZ HUGH LANE.

MARCH 1973 By ALEXANDER LAING '25