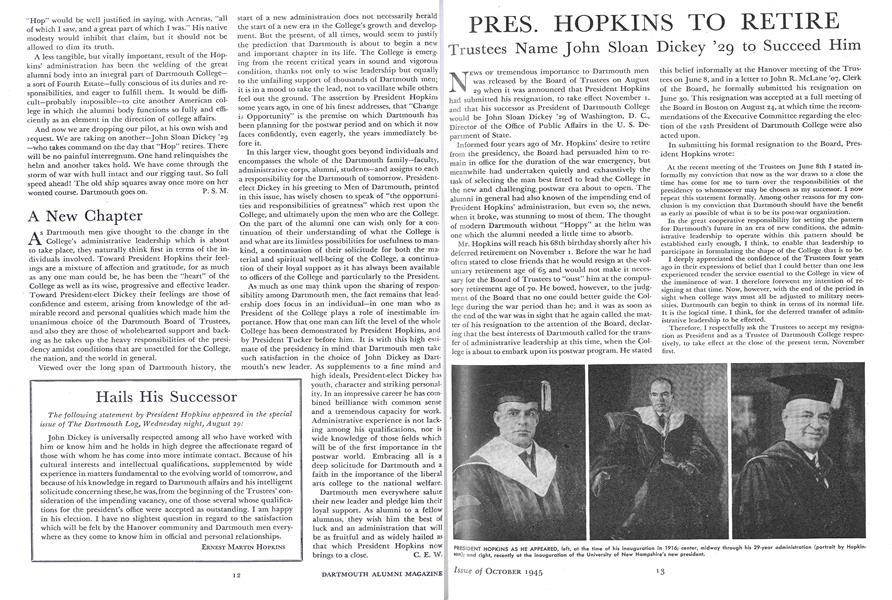

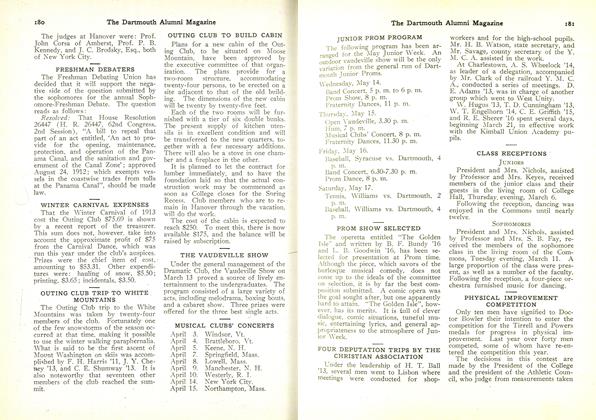

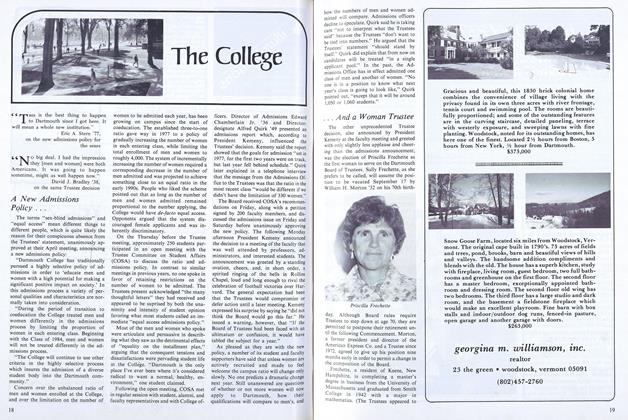

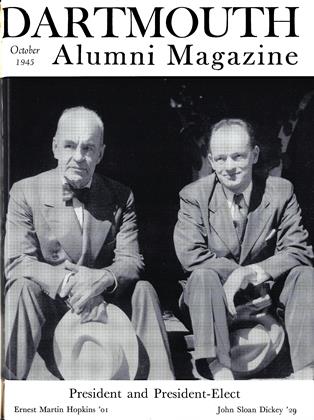

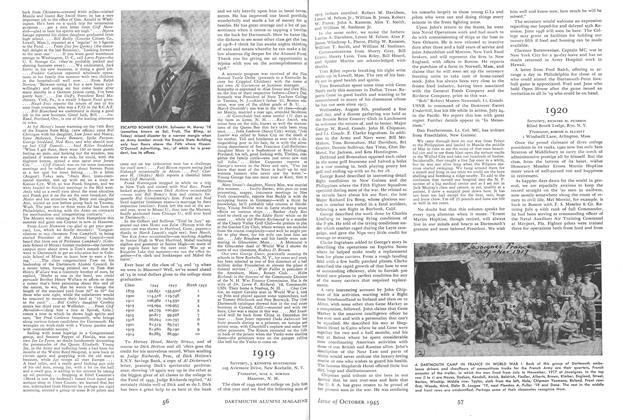

ON the first day of November next, Ernest Martin Hopkins will retire from the presidency of Dartmouth College, the office which he has held for nearly thirty years. This announcement, made public in the closing days of August, brought a pang of regret to every Dartmouth man the wide world over and never in all our history have the thousands of Dartmouth alumni been so widely scattered about this girdled earth as now, in the closing days of humanity's greatest war. One knew that eventually this must come, but one hoped that the coming would be long postponed. "Hop" for let us lay aside ceremonial stiffness and call him by the name we all userichly deserves a respite from the official cares he has borne so long and made to be so nobly fruitful; yet there is not one of us who did not cherish the wish that the president who had brought Dartmouth to the summit of her usefulness and fame would delay his going. It was not so to be.

It is needless to recapitulate here the story of "Hop's" administration from 1916 to 1945. The record lies open for every visitor to Hanover to read. If one seeks a

monument it is manifest to any one who looks about him. The "little college" which Wheelock founded, which Webster saved from extinction, and which Tucker revitalized and refounded in the middle '9os, attained under the Hopkins' administration its 175 th year, greater in size, broader in scope, sounder in organization, better equipped in plant and personnel than the most sanguine among us had ever dared to dream. As always in such matters, many contributed to this result; but it was mainly "Hop's" doing, and without his leadership and inspiration nothing like it would have been possible. God has been very good to Dartmouth in raising up the right men at the right time to deal with Dartmouth's crises.

A moment's reflection will probably convince any candid observer that the president's decision to retire is just and timely, sincerely as one must regret the making of it. Not only does President Hopkins merit leisure for the years that remain a leisure nobly won by three decades of self-sacrificing service. One must bear in mind also the compelling fact that we face what appears to be a different sort of world, different from any that mankind has ever known, with different requirements which are bound to affect collegiate education. Since, in the nature of things, new hands must soon take up and deal with these new problems, it is obviously best to let new hands and new minds handle all this ab initio, and not hamper them with inherited ideas which quite possibly would not fit the new conditions of what men already begin to call the Atomic Age. Venienti occurite morbo. When an unwelcome

contingency is approaching it is better to go forth and meet it than to delay and postpone.

Looking back down the vista of the years, as it is possible for those to do who have known Dartmouth through the lapsed years of the Twentieth Century, one recalls the inauguration of President Hopkins in 1916 a young man of 38, only fifteen years out of college, and drafted from the ranks of progressive business men; not a teacher; not a professional scholar. He had no academic background aside from such as his own student years and his term as a secretary and intimate assistant to Dr. Tucker afforded. But what an inspired choice it was! "Hop" had caught from Dr. Tucker that divine spark that had made Tucker the idol of the Dartmouth of his day; and that Promethean fire he kept alive until called to the presidency himself, whereupon it was fanned to new flame.

If one were to seek the innermost secret of President Hopkins' success, it would probably be found in his gift of rugged New England common sense, which enabled him not only to manifest firmness in the right as it is given us human beings to see the right, but also to know the right when he saw it. With him it has not been haphazard guesswork, or wishful thinking, or pious aspiration, or idealistic rainbow-chasing. It has been just good, solid common sense —something not too often found among educators in this or any other age. Under his administration, Dartmouth has come unto her own. She has weathered two gigantic wars and a major economic depression, yet has gone on growing. The events of those thirty years have been impressive; and "Hop" would be well justified in saying, with Aeneas, "all of which I saw, and a great part of which I was." His native modesty would inhibit that claim, but it should not be allowed to dim its truth.

A less tangible, but vitally important, result of the Hopkins' a dministration has been the welding of the great alumni body into an integral part of Dartmouth College a sort of Fourth Estate—fully conscious of its duties and responsibilities, and eager to fulfill them. It would be difficult—probably impossible—to cite another American college in which the alumni body functions so fully and efficiently as an element in the direction of college affairs.

And now we are dropping our pilot, at his own wish and request. We are taking on another—John Sloan Dickey '29 —who takes command on the day that "Hop" retires. There will be no painful interregnum. One hand relinquishes the helm and another takes hold. We have come through the storm of war with hull intact and our rigging taut. So full speed ahead! The old ship squares away once more on her wonted course. Dartmouth goes on.

PRESIDENT HOPKINS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHARRY L. HILLMAN

October 1945 By SIDNEY C HAZELTON '09, -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S NEW LEADER

October 1945 -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

October 1945 By H. F. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

October 1945 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS -

Sports

SportsTHE FOOTBALL OUTLOOK

October 1945 By Francis E Merrill '26