MR. HENRY MILLER has once before been guest columnist. At this time, believing it will interest the readers of this column, I want to print a most interesting statement by Miller concerning genius and Thomas Wolfe. His remarks follow:

I don't think a writer becomes a genius, especially by writing unreadable books; I think he is born a genius, and no matter what sort of books he writes the fact remains ineluctable. As to what constitutes genius, how it manifests itself, and so on, that will always be a matter for endless debate.

I agree with Mr. McFee that there is a pathetic desire among Americans to discover some great figure of their own who will compare with those of Europe. It is more than probable that the ballyhoo about Wolfe sprang from this urge. But that is not to deny that certain qualities of Wolfe do legitimately inspire such comparison. The fact that Wolfe needed help, the fact that he seems to some of us unreadable, may only prove that he was attempting to cope with problems that were beyond him. I admire him for the effort. And that is precisely where he differs from the so-called novelist, for Wolfe wasn't a novelist at all. Wolfe was something greater than a mere novelist. Mr. McFee is concerned to know whether I regard a novelist who is readable as wooden. Not necessarily. But the novel is an outmoded vehicle; as a form it has long been exhausted. A man may still write a good novel, but in doing so he is not making a contribution to creative letters. If I had to choose between reading the best novels of our epoch and the unreadable books of Thomas Wolfe I believe I would choose Wolfe. I would prefer to live with the man who struggled and failed rather than with the one who swims with the tide and has had his little success.

What I tried to point out, however, in my review of the "Letters," is that Wolfe's case is symbolic and tragic. The set-up which a man of letters who has originality is obliged to confront in a country like ours is the worst possible one. I don't think Wolfe failed so much as did his countrymen. To have been born with his gifts was to be doomed from the start. We pine for men of originality, men of genius, but we do nothing to encourage them. The publishers and critics are only partially responsible; the fault goes deeper. The whole American people are to blame. Today it is Thomas Wolfe who goes to the guillotine; tomorrow it is another man. Examine the lives of the few men of genius we produced; it is a tale of horror. The amazing thing to me is that Wolfe retained as much lucidity as he did. He might have gone completely gaga. I for one am sorry he didn't.

As for the money problem Of course Wolfe was preoccupied with it. So was Balzac, so was Dostoievski, so was Beethoven, so was Van Gogh. Who isn't in a crazy world which rewards the mediocrity and lets the man of genius starve to death? Mr. McFee seems to imply that because he was able to earn a living at something else while writing his books a genius ought to be able to do so too. But it's one of the characteristics of a genius that he's singleminded, that he gives his all to the thing in hand, that he will let his wife and children starve rather than abandon the creation which obsesses him. Wolfe was not obsessed with the desire to make money but with the desire to express himself sincerely and exhaustively. He needed money to live, and if his appetites were large it was because he was a big soul and his hunger was extraordinary in every realm. "This," said Schopenhauer, "explains the restless activity of the genius, for the present can rarely satisfy him, because it does not fill his thoughts. There is in him a ceaseless inspiration and desire for new and lofty things, and a longing to meet and communicate with others of similar status. The common mortal, on the other hand, filled with the hour, ends in it, and finding everywhere his like enjoys that satisfaction in daily life from which the genius is debarred."

I should like to add a few recommendations to Mr. Miller's interesting comments on Wolfe.

I have not yet read Santayana's heralded autobiography but I can recommend two others which I think you would enjoy. One is Wilbur Cross's ConnecticutYankee (Yale Press) which, though there is a little too much about Yale (for nonYale men) and too much about the governorship, contains much shrewd observation and reveals a long and valuable life. He has had too much academic training to spill over but he does reveal a human being, much more in fact, than most Yankees are capable of revealing. The other is Ferris Greenslet's Under theBridge which comes close to being a little masterpiece, better I think, than his friend John Buchan's Pilgrim's Way. Don't miss this one. It is mellow, charming, and delightfully written.

Another Yale Press book which I am glad to have, and to browse in, is TheForgotten Man's Almanac being rations of common sense from the works of William Graham Sumner. Sumner is a long way from being forgotten but he had the kind of a mind, uncompromising, honest, and sharp, which we need today. If it leads you to his Folkways so much the better. There are extracts from his works for the 365 days of the year.

The fairest and most complete account of coal and the industry that I have seen is McAlister Colman's excellent book Men and Coal (Farrar). This seems to me required reading for those interested in labor and industry now and after the war.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

February 1944 -

Article

ArticleWOMEN OF DARTMOUTH

February 1944 By BILL CUNNINGHAM '19 -

Article

ArticleTHE POSTWAR MAJOR

February 1944 By Harold E: B. Speight h'28, -

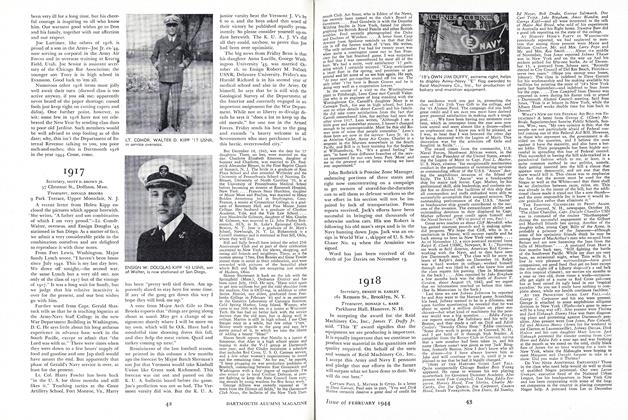

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1944 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

February 1944 By WILLIAM C. EMBRY -

Article

ArticleBUTTERFIELD HALL

February 1944 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON 'OO

HERBERT F. WEST '22

-

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

April 1938 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

January 1942 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksSHORT CUT TO TOKYO,

October 1943 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

April 1947 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

January 1948 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksTHE HONEST RAINMAKER.

April 1953 By Herbert F. West '22