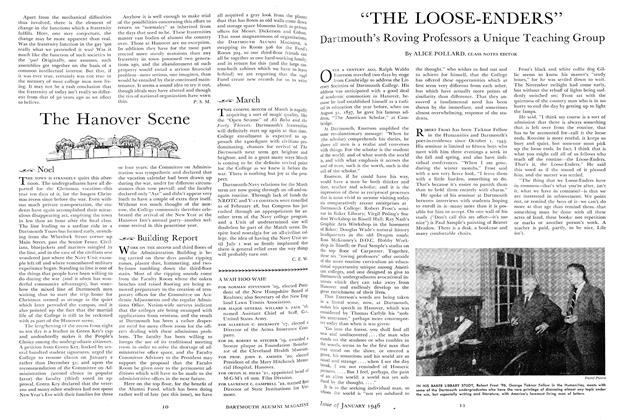

Speculation as to what colleges are going to be like after the war is probably as futile as are the fascinating speculations to which men are prone concerning the shape of things to come in all other respects. That futility does not at all deter commentators from guessing and predicting, however, and the casual eye can detect a growing belief that there will be a swing away from the system of free electives toward that which involves a revival—partial though it may well be—of the requirement of courses leading to the Baccalaureate degree.

What it amounts to is a growing conviction that the idea of free electives, greatly furthered if not actually originated by President Eliot of Harvard half a century ago, has been harmfully overdone. There seems to be a tendency, sometimes in surprising quarters, to discover virtues in what one may call the table d'hote, ,as contrasted with the cafeteria (or a la carte) theory of education.

Not every boy of 18 is equipped with the discernment required to order a good educational dinner. As a matter of fact, very few are so endowed. Agreeable as it may be to wander at will through an alluring display of educational dishes, with freedom to serve oneself according to the whims of the individual, it cannot be guaranteed that the result will be a properly balanced intellectual ration. It is much more likely that the choice will be determined by something other than a zeal to assimilate the essential vitamins. Hence the question whether or not it wasn't better for educational health when colleges operated almost entirely on the table d'hote theory, with very little consideration of potential allergies, and required their students to partake of what was set before them.

It is a human failing to swing from one extreme to another, and this is as commonly manifested in educational matters as in any other. The rigid requirements of a century ago in the matter of college curricula were seen to be altogether too rigid, suggesting the desirability of a wider choice for the student. And now we find educators deploring the fact that the choice has been made entirely too wide, in view of the fact that too few are gifted with the discriminating faculty needed to produce a well-rounded result. If the table d'hote theory was overdone, so has been the cafeteria system. Young students are prone to select only the fare that appeals to themperhaps the fare that is easiest to takein complete ignorance of intellectual dietetics, or deliberate defiance thereof. Freedom is a grand thing if you know how to use it. Otherwise it may be a dubious blessing.

In the days when only a chosen few sought college education it was easier to maintain a fixed intellectual regimen. In these days when all the world seems to be going to college it is too easy for freedom of choice to be abused. What seems most reasonable to believe is that the curriculum of the future will be a temperate combination of the two ideas, less elastic than that of recent years and less rigid than that of our grandfathers' day, but somewhat more tolerant of required subjects than would have seemed possible a dozen years ago.

One guess is as good, or as bad, as another, no doubt. But at least the folly of a loosely overseen "cafeteria" system is widely appreciated, as evidenced by thoughtful writers, even in quarters originally hospitable to so-called "progressive" ideas in education.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorRound the Girdled Earth

June 1944 -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

June 1944 By H. F. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

June 1944 By EDWIN A. BOCK, WILLIAM T. MAECK -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S SKIPPER

June 1944 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

June 1944 By MOTT D. BROWN JR., DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1944 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR

P. S. M.

-

Article

ArticleAn Academic Volte-Face

December 1942 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleThat Fourth Freedom

May 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleHurry, Hurry, Hurry!

August 1944 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleLarboard Watch, Ahoy!

August 1945 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleA Lively Relic

January 1946 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleThe Fourth Estate

May 1946 By P. S. M.

Article

-

Article

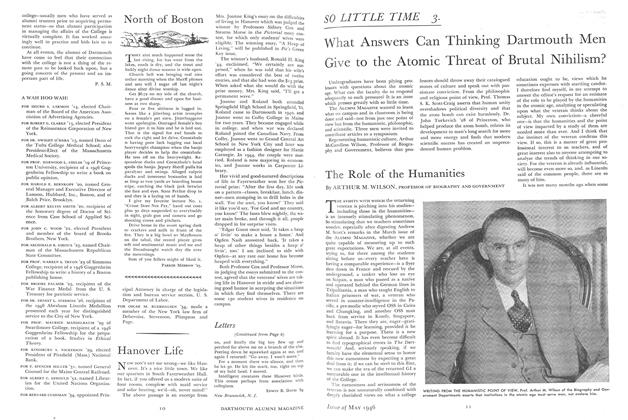

ArticleTHAYER SCHOOL LECTURES

March 1921 -

Article

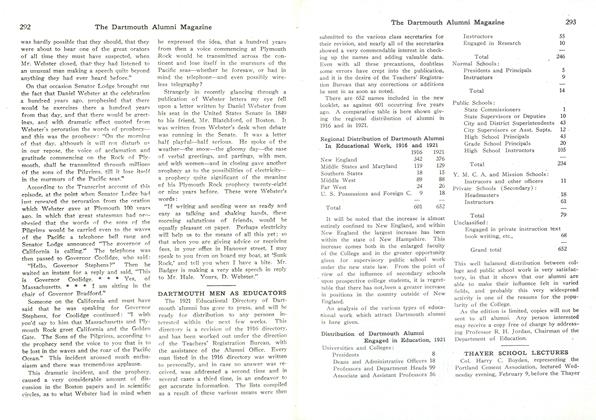

ArticleThe Results

APRIL • 1985 -

Article

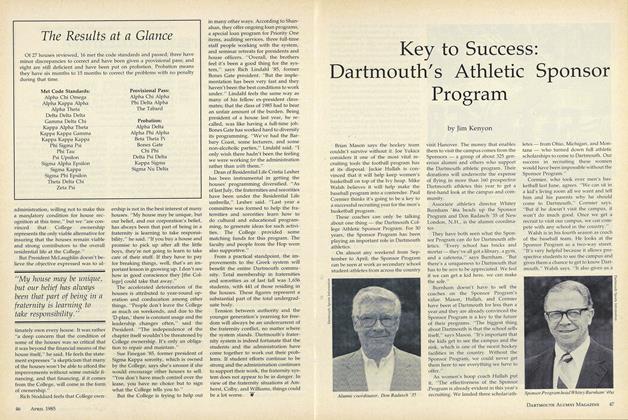

ArticleA new year begins

NOVEMBER • 1987 -

Article

ArticleAfternoons With Frost

October 1973 By FIERMANJ. OBERMAYER '46 -

Article

ArticleThe Fund Goes to Work

June 1961 By RAY BUCK '52 -

Article

ArticleFisher Interns Study Advertising and Public Relations

DECEMBER • 1985 By SKIP STURMAN '70