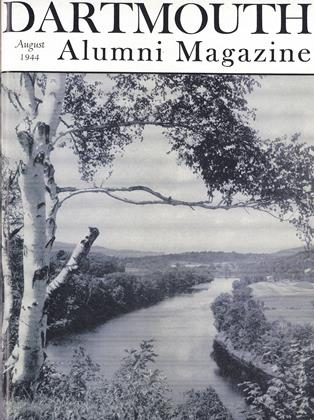

THE BURNING QUESTION among educators just now seems to concern the nature of colleges after the war. We have arrived at a time when one is apparently permitted to think the Allied Nations are going to win, and win within a reasonably short time, so that problems concerning postwar colleges loom as pressing for attention. Just what form the liberal arts education shall take when normal times return is only one of the questions to be discussed. Another concerns the length of time to be devoted to fitting young men—and women—for the fellowship of educated people; i.e., whether it will or will not be desirable to project into the future the "streamlining" of the present, with Bachelors of Arts rolling off the assembly line at record speed.

Opinions differ so markedly on this point that a layman may be pardoned for some hesitation in proffering his two-cents'- worth; but the present writer inclines to side with those who feel that the hurry-up program made almost universal by the stress of war should not be adhered to when peace returns—at least in the case of the liberal arts colleges. It has been found advantageous during the period of stress to operate such colleges on a year-'round basis, so that young men destined for induction into the armed forces within a year or so might get as far along on the road to an A.B. degree as circumstances would permit before the call came to go into active service. One may doubt that the results of such accelerated education are good enough to warrant prolonging the system into years when the need of such haste will no longer exist.

To be sure, there are some eminent educators who feel that two years, or two and a half, should be amply sufficient to enable all the teaching really necessary to the baccalaureate degree, but it seems a proposition beset by enough doubt to warrant a gingerly inspection before accepting it. The colleges have been speeding up their courses only because they had to meet the stern conditions of warfare. It has been hard, not only on the students, but also on the faculty, to have to maintain such a driving gait, with term following term at inconsiderable intervals of only a week or ten days. It is quite possible we need more of the deliberative in our system—more time for the digestive process of the youthful intellect, to the end that this forced feeding may not outrun assimilation.

Certain traditional incidentals, such as the creation and preservation o£ class spirit, are sure to suffer from the accelerated process, and such things have an important bearing on the conduct of every college. On the whole, then, one may deplore the headlong haste involved in making Bachelors of Arts in two years or so, without incurring the obloquy of seeming a hidebound reactionary. The necessity of all this rush will ultimately diminish, and very probably will disappear. After all, a college is not susceptible to all the requirements of industrial mass production. Too much streamlining may easily be as bad .as too much devotion to contemplative study—and perhaps even worse. By derivation the word "scholarship" connotes something of the leisurely.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleA TEACHING LIBRARY

August 1944 By NORMAN K. ARNOLD -

Article

ArticleTHE HISTORIC COLLEGE

August 1944 -

Article

ArticleALUMNI OFFICERS MEET

August 1944 -

Article

ArticleTHE 50-YEAR MESSAGE

August 1944 By REV. CHARLES C. MERRILL '94 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1904

August 1944 By DAVID S. AUSTIN II, THOMAS W. STREETER -

Article

ArticleMAN WITH COW SENSE

August 1944 By A. P.

P. S. M.

-

Article

ArticleSea-Anchor for Dartmouth

January 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleThe Overmastering Need

February 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleWorship of the Plan

April 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleHistory Again

February 1944 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleRallentando

February 1946 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleThe Guinea's Stamp

May 1946 By P. S. M.