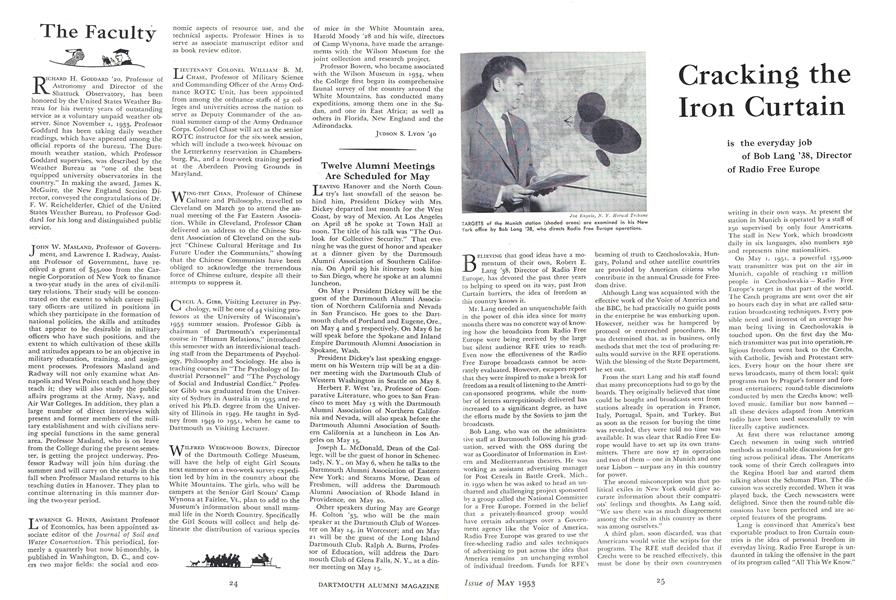

is the everyday job of Bob Lang '38, Director of Radio Free Europe

Believing that good ideas have a momentum of their own, Robert E. Lang '38, Director of Radio Free Europe, has devoted the past three years to helping to speed on its way, past Iron Curtain barriers, the idea of freedom as this country knows it.

Mr. Lang needed an unquenchable faith in the power of this idea since for many months there was no concrete way of knowing how the broadcasts from Radio Free Europe were being received by the large but silent audience RFE tries to reach. Even now the effectiveness of the Radio Free Europe broadcasts cannot be accu- rately evaluated. However, escapees report that they were inspired to make a break for freedom as a result of listening to the American-sponsored programs, while the number of letters surreptitiously delivered has increased to a significant degree, as have the efforts made by the Soviets to jam the broadcasts.

Bob Lang, who was on the administrative staff at Dartmouth following his graduation, served with the OSS during the war as Coordinator of Information in Eastern and Mediterranean theatres. He was working as assistant advertising manager for Post Cereals in Battle Creek, Mich., in 1950 when he was asked to head an uncharted and challenging project sponsored by a group called the National Committee for a Free Europe. Formed in the belief that a privately-financed group would have certain advantages over a Government agency like the Voice of America, Radio Free Europe was geared to use the free-wheeling radio and sales techniques of advertising to put across the idea that America remains an unchanging symbol of individual freedom. Funds for RFE's beaming of truth to Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland and other satellite countries are provided by American citizens who contribute in the annual Crusade for Freedom drive.

Although Lang was acquainted with the effective work of the Voice of America and the BBC, he had practically no guide posts in the enterprise he was embarking upon. However, neither was he hampered by protocol or entrenched procedures. He was determined that, as in business, only methods that met the test of producing results would survive in the RFE operations. With the blessing of the State Department, he set out.

From the start Lang and his staff found that many preconceptions had to go by the boards. They originally believed that time could be bought and broadcasts sent from stations already in operation in France, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and Turkey. But as soon as the reason for buying the time was revealed, they were told no time was available. It was clear that Radio Free Europe would have to set up its own transmitters. There are now 27 in operation and two of them one in Munich and one near Lisbon surpass any in this country for power.

The second misconception was that political exiles in New York could give accurate information about their compatriots' feelings and thoughts. As Lang said, "We saw there was as much disagreement among the exiles in this country as there was among ourselves."

A third plan, soon discarded, was that Americans would write the scripts for the programs. The RFE staff decided that if Czechs were to be reached effectively, this must be done by their own countrymen writing in their own ways. At present the station in Munich is operated by a staff of 250 supervised by only four Americans. The staff in New York, which broadcasts daily in six languages, also numbers 250 and represents nine nationalities.

On May 1, 1951, a powerful 135,000-watt transmitter was put on the air in Munich, capable of reaching 12 million people in Czechoslovakia Radio Free Europe's target in that part of the world. The Czech programs are sent over the air 20 hours each day in what are called saturation broadcasting techniques. Every possible need and interest of an average human being living in Czechoslovakia is touched upon. On the first day the Munich transmitter was put into operation, religious freedom went back to the Czechs, with Catholic, Jewish and Protestant services. Every hour on the hour there are news broadcasts, many of them local; quiz programs run by Prague's former and foremost entertainers; round-table discussions conducted by men the Czechs know; wellloved music, familiar but now banned all these devices adapted from American radio have been used successfully to win literally captive audiences.

At first there was reluctance among Czech newsmen in using such untried methods as round-table discussions for getting across political ideas. The Americans took some of their Czech colleagues into the Regina Hotel bar and started them talking about the Schuman Plan. The discussion was secretly recorded. When it was played back, the Czech newscasters were delighted. Since then the round-table discussions have been perfected and are accepted features of the programs.

Lang is convinced that America's best exportable product to Iron Curtain countries is the idea of personal freedom in everyday living. Radio Free Europe is undaunted in taking the offensive in the part of its program called "All This We Know." This exposes collaborators in satellite countries who collaborate beyond the call of normal survival. Sadistic guards at forced labor camps, the murderer of a parish priest, factory workers who are stool pigeons all these have been called by name by announcers on Radio Free Europe stations. An intelligence network not only supplies the names of the offenders but what happens after these have been publicized. A Rumanian guard named as a cruel tormenter was promptly rewarded by a promotion by his government. Another collaborator after being identified committed suicide. Some informers mentioned on the RFE programs are shifted by the Reds to other areas, to preserve their usefulness.

Proceeding on its assumption that boldness is the best policy, RFE uses an effective device for nailing false Communist propaganda. This was first tried out on May 1, 1951, when the new Munich transmitter was inaugurated. At 7 p.m. the Czech listeners were told to tune into the news broadcast from Prague and then at 7:30 to turn the dial back to the Munich station, for a re-digest of the satellite version of the news. Another method for showing up Soviet propaganda is done through the RFE program, "How to Read Your Newspapers." The Czech audience is asked to turn to some specific account, perhaps in Prague's Rude Pravda. Then the RFE commentator, quoting international press sources, refutes the Soviet-sponsored writeup. Sending balloons with messages into Iron Curtain countries has also been found to be effective.

After three years of hard work, Lang says of the Munich RFE station, "For 20 hours a day it entertains, educates, encourages the people of Czechoslovakia. It actually has become in the minds of the Czechs not a propaganda instrument but their real domestic radio transmitter. The station may be outside the present borders but otherwise it represents the thinking, hopes and desires of Czechoslovakia." Similar transmitters are reaching Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, Rumania and Albania.

A problem growing out of the increased numbers of escapees who have fled into Western zones with a renewed hope for individual freedom has still to be met. Recently a drive by the National Committee for a Free Europe was successful in raising funds both from government and private sources for aid to these refugees. The Czech government has twice protested this aid. Such results as these would seem to confirm Bob Lang's faith that the American idea of the equality of men is still as full of dynamite as it was in Revolutionary days, and that, if boldly helped with American techniques of marketing and salesmanship it can do wonders in keeping the people of satellite countries thinking of freedom, and in preventing them from drifting into apathy and hopelessness about an independent way of life at present denied them.

TARGETS of the Munich station (shaded areas) are examined in his New York office by Bob Lang '38, who directs Radio Free Europe operations.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Lotteries

May 1953 By PHILIP G. NORDELL '16 -

Article

ArticleBaker's Friends

May 1953 By PROF. HERBERT F. WEST '22, SECRETARY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1953 By RICHARD A. HOLTON, ERNEST H. EARLEY -

Article

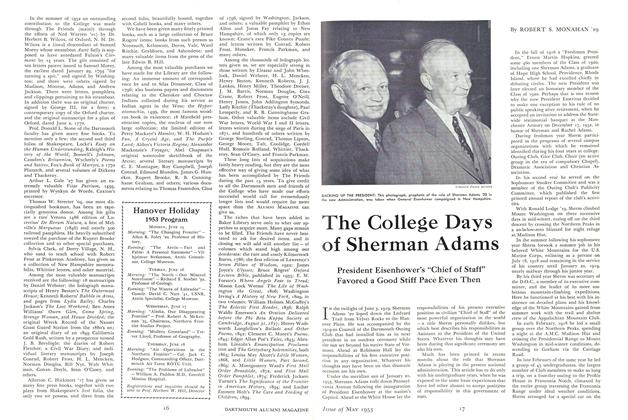

ArticleThe College Days of Sherman Adams

May 1953 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

May 1953 By GEORGE B. REDDING, F. WILLIAM ANDRES -

Class Notes

Class Notes1928

May 1953 By OSMUN SKINNER, GEORGE H. PAS FIELD, WILLIAM COGSWELL

A. P.

Article

-

Article

ArticleBRITISH JOURNALIST LECTURES

March 1920 -

Article

ArticleYoung Is 1940 Captain

January 1940 -

Article

ArticleHopkins Institute debuts

MARCH • 1987 -

Article

ArticleJust One Question

MARCH 1999 -

Article

ArticleSpotlight

Jan/Feb 2006 -

Article

ArticleFOURTH ANNUAL MEETING OF THE ASSOCIATION OF SECRETARIES

FEBRUARY, 1908 By ERNEST M. HOPKINS.