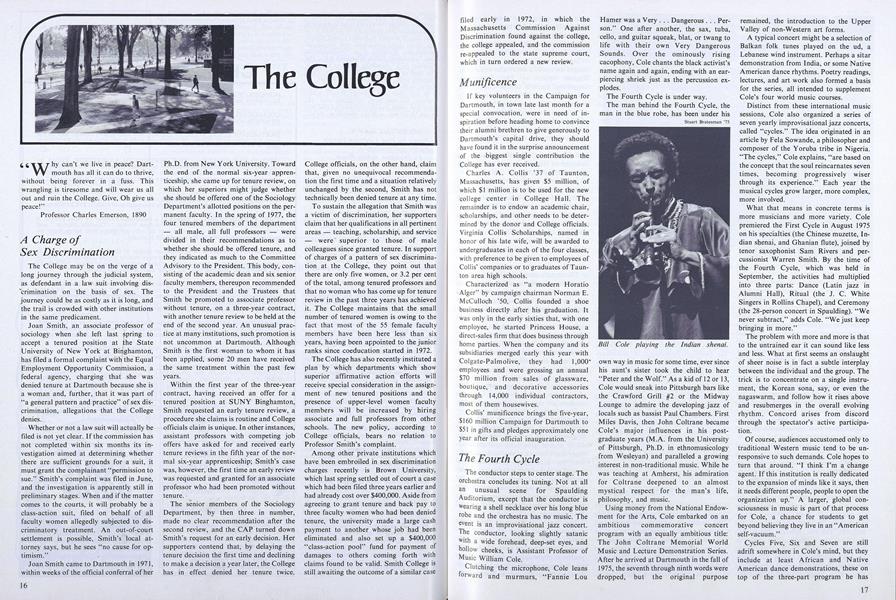

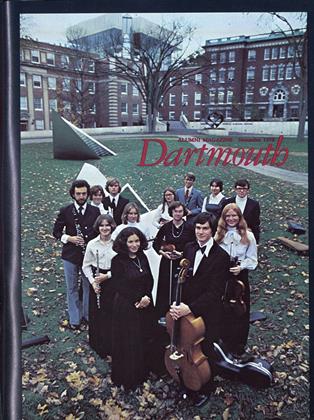

The conductor steps to center stage. The orchestra concludes its tuning. Not at all an unusual scene for Spaulding Auditorium, except that the conductor is wearing a shell necklace over his long blue robe and the orchestra has no music. The event is an improvisational jazz concert. The conductor, looking slightly satanic with a wide forehead, deep-set eyes, and hollow cheeks, is Assistant Professor of Music William Cole.

Clutching the microphone, Cole leans forward and murmurs, "Fannie Lou Hamer was a Very ... Dangerous ... Person." One after another, the sax, tuba, cello, and guitar squeak, blat, or twang to life with their own Very Dangerous Sounds. Over the ominously rising cacophony, Cole chants the black activist's name again and again, ending with an earpiercing shriek just as the percussion explodes.

The Fourth Cycle is under way. The man behind the Fourth Cycle, the man in the blue robe, has been under his own way in music for some time, ever since his aunt's sister took the child to hear "Peter and the Wolf." As a kid of 12 or 13, Cole would sneak into Pittsburgh bars like the Crawford Grill #2 or the Midway Lounge to admire the developing jazz of locals such as bassist Paul Chambers. First Miles Davis, then John Coltrane became Cole's major influences in his postgraduate years (M.A. from the University of Pittsburgh, Ph.D. in ethnomusicology from Wesleyan) and paralleled a growing interest in non-traditional music. While he was teaching at Amherst, his admiration for Coltrane deepened to an almost mystical respect for the man's life, philosophy, and music.

Using money from the National Endowment for the Arts, Cole embarked on an ambitious commemorative concert program with an equally ambitious title: The John Coltrane Memorial World Music and Lecture Demonstration Series. After he arrived at Dartmouth in the fall of 1975, the seventh through ninth words were dropped, but the original purpose remained, the introduction to the Upper Valley of non-Western art forms.

A typical concert might be a selection of Balkan folk tunes played on the ud, a Lebanese wind instrument. Perhaps a sitar demonstration from India, or some Native American dance rhythms. Poetry readings, lectures, and art work also formed a basis for the series, all intended to supplement Cole's four world music courses.

Distinct from these international music sessions, Cole also organized a series of seven yearly improvisational jazz concerts, called "cycles." The idea originated in an article by Fela Sowande, a philosopher and composer of the Yoruba tribe in Nigeria. "The cycles," Cole explains, "are based on the concept that the soul reincarnates seven times, becoming progressively wiser through its experience." Each year the musical cycles grow larger, more complex, more involved.

What that means in concrete terms is more musicians and more variety. Cole premiered the First Cycle in August 1975 on his specialties (the Chinese muzette, Indian shenai, and Ghanian flute), joined by tenor saxophonist Sam Rivers and percussionist Warren Smith. By the time of the Fourth Cycle, which was held in September, the activities had multiplied into three parts: Dance (Latin jazz in Alumni Hall), Ritual (the J. C. White Singers in Rollins Chapel), and Ceremony (the 28-person concert in Spaulding). "We never subtract," adds Cole. "We just keep bringing in more."

The problem with more and more is that to the untrained ear it can sound like less and less. What at first seems an onslaught of sheer noise is in fact a subtle interplay between the individual and the group. The trick is to concentrate on a single instrument, the Korean sona, say, or even the nagaswarm, and follow how it rises above and resubmerges in the overall evolving rhythm. Concord arises from discord through the spectator's active participation.

Of course, audiences accustomed only to traditional Western music tend to be unresponsive to such demands. Cole hopes to turn that around. "I think I'm a change agent. If this institution is really dedicated to the expansion of minds like it says, then it needs different people, people to open the organization up." A larger, global consciousness in music is part of that process for Cole, a chance for students to get beyond believing they live in an "American self-vacuum."

Cycles Five, Six and Seven are still adrift somewhere in Cole's mind, but they include at least African and Native American dance demonstrations, these on top of the three-part program he has already. As might be expected, Cycle Seven will be of epic proportions, something like a week of festivities concluding with a jazz concert in New York City.

Some might find it curious that an assistant professor working under a six-year program toward tenure would plan out a series seven years in advance. To any jokes on the subject, Cole just laughs. "If I have to, I'll take the Seventh Cycle with me as part of a contract with a new school. But I set up the program to play at Dartmouth, and I hope I can keep it here throughout — it's a pretty good place, you know."

Bill Cole playing the Indian shenai.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

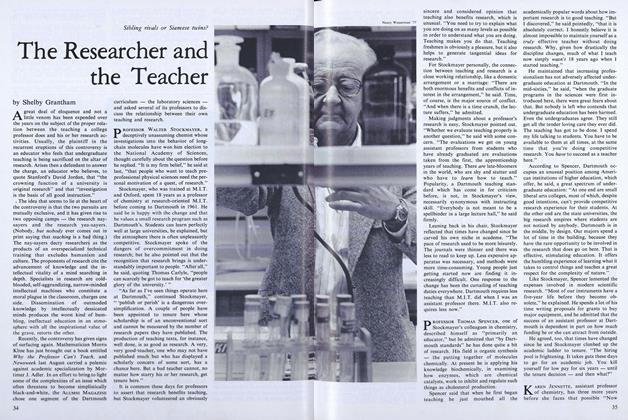

FeatureThe Researcher and the Teacher

November 1978 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureJazz Comes to College

November 1978 By Dick Holbrook -

Feature

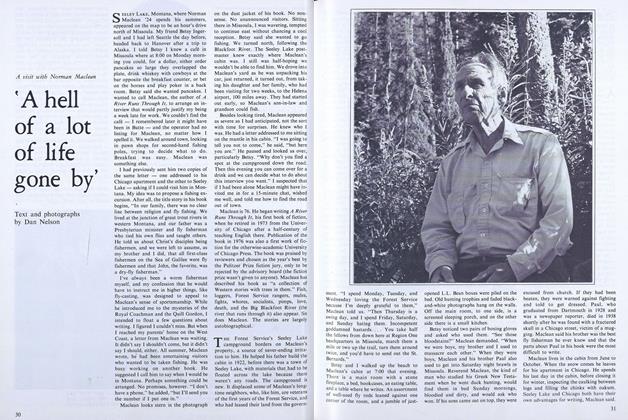

Feature'A hell of a lot of life gone by'

November 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureMaking Music

November 1978 By Dana Grossman -

Article

ArticleThe Joy of Moving

November 1978 By W.B.C. -

Article

ArticleMan of the Cloth

November 1978 By M.B.R.