FOR THE PURPOSES of this article the complex of deliberation and action called "foreign policy" will be divided arbitrarily into three components: determination of this country's fundamental interest; attainment of this interest by means other than war; attainment of it by the threat of war, or by war. The bases of our policy toward Europe will be discussed under these three headings.

Clear perception of a country's fundamental interest, to which all others are ancillary and on which all others depend, is the prerequisite for the formulation of a sound foreign policy. Once this interest has been defined the primary mission of the country's foreign policy has also been defined: the protection of this interest. Then, and only then, it becomes possible to evolve a policy which can discriminate between essential and non-essential issues, which does not permit itself to be blinded by emotion, however natural, and which can command the support of the nation if it must eventually be enforced. The writer of this article believes that the fundamental determinant of our foreign policy today is the decision whether we do, or do not, intend to remain a capitalistic country. The discussion which follows rests upon the premise that we do intend to retain our present economic system.

The foreign policy of a capitalistic country will logically aim at the preservation or creation of conditions throughout the world which are favorable to a capitalistic economy and to capitalistic institutions. The chief obstacle to this economy and to these institutions in Europe is communism, a system opposed to ours and, in the long run, incompatible with it, at least in the present forms of both systems. The champion of communism is Soviet Russia, a land empire comprising one sixth of the with a large and steadily increasing population, nearly all of the natural ingredients of industry, a vigorous autocratic leadership devoted to realizing the country's unprecedented industrial potential, and formidable military power. The leaders of this empire have consistently prouations claimed its implicit hostility to capitalism. These are facts which the personal inclinations of private individuals or the goodwill of statesmen cannot, unfortunately, affect. They can be obscured temporarily for immediate reasons, as they were to a certain extent during the last war, but they do not cease, and have not ceased, to exist, nor can they while we represent one system and its way of life, and the Russians the other. Our basic interest, the preservation of capitalism, implies our opposition to the spread of communism in Europe.

The guiding principle of a country's foreign policy may often be stated quite simply, and it should be understood, with its implications, by every citizen. The expression of that principle through diplomacy may become exceedingly complicated in a situation involving a specific set of conditions and specific tactics. As particular sitearth, differ the methods of diplomacy may differ while the underlying policy remains the same. It is difficult for anyone not in the foreign service to arrive at an accurate evaluation of our policy in connection with any one European problem. Our opinions are usually derived almost exclusively from the reports of newspaper correspondents who are themselves denied access to the rooms where secret decisions are reached on the basis of secret information. Few of them, and fewer of us, have a sufficiently detailed and current knowledge of the political and economic dynamics of any European country to justify criticism of the policy which the United States might follow in a particular issue of foreign affairs involving that country. In doing so we show praiseworthy alertness, and exercise our right as citizens of a democracy, but our conclusions are frequently valueless because they are based on inadequate knowledge of the European country in question, or because we do not know what policy our diplomats are actually following, or, above all, because we do not relate a specific problem to the larger problem of our fundamental interest in Europe and the,world. Applying these considerations to himself, the writer will not attempt the detailed treatment of any individual European problem, and will confine himself to outlining the general application of a basic policy resulting from the basic interest of this country as stated above.

At the present time Europe may be regarded as divided into a Russian zone and a non-Russian zone. Beyond her pre-war frontiers Russia holds the Baltic states and Finland, Poland, a large part of Germany, Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Rumania, Bulgaria and Yugoslavia. The western allies hold a part of Germany and all of Italy, while their influence is decisive in France and the Low Countries. Spain is isolated. The other Scandinavian countries would probably be more accessible to Russian strength in a test than to ours or Britain's. On the other hand the status of the strategically placed Italian colonies of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, as well as of the Dodecanese islands, could presumably be determined by Anglo-American air and sea power.

It is to be anticipated that Russian influence will be predominant throughout the zone of her occupation. It is unlikely that she will permit our representatives much freedom to explore and report upon the details of her policy inside her zone, let alone grant us any voice in her decisions, as some Americans appear to expect. We may also anticipate that Russia will favor the spread of communism in the areas she controls, and that this process will be facilitated by the economic dislocation of these areas with its inevitable consequence of an unsatisfactory standard of living. In this connection it should be noted that time will be working for Russia and that the growth of communism in the Russian occupied zone may not require her active encouragement. Since the course of events in this zone cannot be interrupted by us except through the instrumentality of an aggressive war we must reckon with the loss to communism of most of Europe.

There remains that part of the continent which is not occupied by Russia and which is responsive to our own influence and that of Great Britain. The correct policy to be followed in regard to the countries of this area derives inevitably from our own vital interest. It is the policy of supporting the capitalistic system in these countries. The precise methods to be used in individual cases lie outside the scope of this article. Their choice and application are for the experts of the State Department to determine, in any case, not for the inexperienced and incompletely informed layman. It is supposed that they would include shipments of food and clothing; loans; and diplomatic support to governments and parties committed to the preservation of capitalism in their countries. We should assist in every way the revival of their industry and trade, knowing that an approximation of prosperity, or at least a rising standard of living, is the best guarantee against the despair which generates popular desire for radical changes in the established order. This policy must logically be applied also to the sectors of Germany occupied by the United States, Great Britain, and France. There is no reason to suppose that our diplomacy would be incapable of securing the cooperation of the other two powers mentioned.

Great Britain is the only functioning capitalistic power extant aside from ourselves. Despite her present government she seems resolved to maintain the capitalist system. She faces severe problems of reconversion, whose solution can be made easier by financial assistance from the United States. It should not be forgotten that in addition to her strategic location she possesses substantial military resources even if she is not a great power in the sense that the United States and Russia are. It serves our vital interest to vote Great Britain the loans she needs in order to pass more easily from a war to a peace economy She needs us, but we need her. It is perhaps not too much to say that capitalism in the two countries will stand or fall together.

The case of Spain demands special mention. Details of the Spanish situation will be excluded for reasons already given. Certain of the more general aspects seem clear. The Franco government is a fascist-clerical dictatorship which was established with the help of Germany and Italy. The foreign policy of this government was proAxis throughout the last war. Spain would probably have entered the war against us if she had been given the means, and had been promised the territorial aggrandizement she named as her price. The character of this government and of its leader arouses loathing and the desire to see both of them overthrown. Before this can be done safely it will be necessary to know the political color and the durability of the succession government. We must be in no doubt as to the intentions and capacities of the available leaders, the extent to which they can actually speak for the Spanish people, the desires of that people, and the prevailing social and economic trends in Spain. These are controversial questions, made more difficult by propaganda and emotion. Our fundamental interest will not allow us to welcome a succession government favorable to communism. The Spanish problem, whatever its unique facets, must be related to the larger problem of the preservation of capitalism.

The discussion so far has dealt with two of the three components of foreign policy: determination of our fundamental inter- est, and the attainment of this interest by means other than war. It has been confined to our relations with powers which are presumably friendly to us, excepting the Franco government in Spain. The means indicated for the implementation of our policy toward these states include material and financial assistance, and the support of our diplomacy. Behind all other kinds of assistance is the question of military aid. The role of military power in foreign af- fairs becomes more prominent when we envisage the maintenance of our vital in- terest against the opposition of states which are not friendly to us. Against a weak, unfriendly state, the denial of ma- terial and financial assistance, accompa- nied by the tacit threat of possible military measures, should be sufficient. The success of such sanctions would, of course, be in inverse proportion to the size, resources and military power of a given state. Against the encroachments of a first-class indus- trial and military power it might normally be possible to assemble a coalition, spon- sored by an international organization, which could apply economic and military sanctions. But today, aside from Russia, the only states possessing economic as well as military power are ourselves and England.

It is hard to escape the conclusion that if our foreign policy is to be successful it must be backed by overwhelming American military power. Without the argument of force behind it, the reasoning of diplomats loses its cogency. The best thoughtout policy remains wishful thinking if it cannot, when necessary, be imposed. The vital interests of a country are defended in an emergency not by their intrinsic righteousness, but by weapons. In the last analysis the very nature of a country's foreign policy depends on the size and quality of its armed forces. Surely it is plain that the full power of the United States should stand behind our diplomacy.

The terrifying reality is that this is not the case. During the past year our army and navy have been largely reduced. The campaign to attract volunteers into the regular army has not produced sufficient replacements to offset losses of personnel through the regular channels of separation from the service. General Eisenhower has admitted the failure to date of the campaign for voluntary enlistment, and has urged that the draft be continued in order to maintain the army at a size commensurate with its possible tasks. In the face of this testimony, and of world unrest, Congress refused to prolong the draft.

Now it is nothing new for Congressmen, in an election year, to place their personal ambitions before national interests. In an election year Congressmen are most sensitive to the opinions of the electorate. Evidently they were convinced that the electorate wanted the draft stopped. If this is so, the conclusion is warranted that the American people, in their desire to return to normalcy, have already forgotten, or no longer care, that we have vital interests abroad for the protection of which we need the utmost power we can muster.

The conduct of foreign affairs in a democracy is subject to hindrances implicit in the democratic system. Crucial decisions in foreign policy are, at least in theory, the product of the popular will. Yet the public is poorly informed as to the stakes involved, and usually not very interested. The people's representatives are sometimes not much better informed. The history of this and other democracies shows that tremendous issues involving the existence of the country concerned have been brought down to the level of party politics, and decided on that basis alone. It is doubtful that the majority of the American people perceived the compelling, but impersonal and seemingly abstract reasons which dictated our entrance into the two wars against Germany. The categoric imperative of geographic, economic and political necessities, however emphatically presented has not been regarded by our people as a sufficient cause for war. Only after we have been actually attacked are we ready to defend our interests. It has proved difficult, in the past, even to persuade the country to protect itself before the tornado of war was upon us. It is disquieting to reflect upon the course of world events if the Axis had not offered us overt violence.

Americans should realize that we are in a period of continuing crisis. It is a time for recognition of our position, our interests and our dangers. It is not a time for paralysis of the national strength through domestic strife. It is not a time when we can allow our judgment to be distorted by prejudice, or passion. The war which ended last year did not answer the great question of the twentieth century. That is the question whether the goods of this world shall be produced and distributed through private or public enterprise. It was the premise of this article that the American people desire to retain the system of private enterprise. Then they must defend the system at home, and support a vigorous foreign policy to defend it abroad. In the pursuit of that policy the writer hopes that, the United States will take for its guidance the words which a wise English foreign secretary used of his country: "She has neither eternal friendships, nor eternal enmities. She has onlyeternal interests."

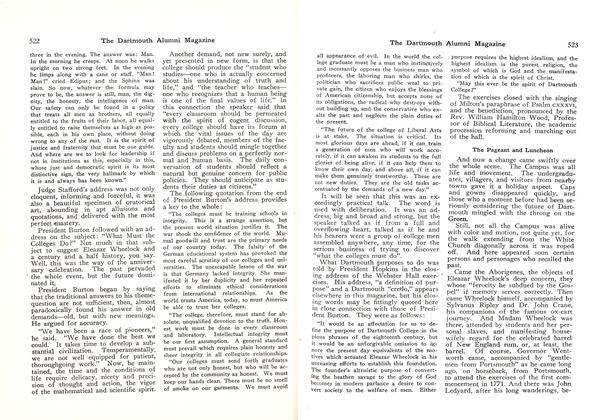

PROFESSOR JOHN C. ADAMS of the Dartmouth History Department, specialist in the field of European history, who writes of United States foreign policy in that complex and troubled area of the world.

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF HISTORY

Professor John Clinton Adams got into the war early with the rank of second lieutenant and got out late with the rank of major. Between May 1942 and October 1945 when he left Europe for the United States, he served time with the MIS in Washington and the Signal Corps in Europe. Born in Philadelphia in 1909, Dr. Adams did his undergraduate work at the University of Pennsylvania and got his M.A. and Ph.D. at Duke. Before 1941 when he came to Dartmouth as an Assistant Professor, he taught a semester at Holmes Junior College in Mississippi, spent a year as Post-doctoral Fellow with the Social Science Research Council, and then went to Princeton for five years as Instructor in Modern European History. Dr. Adams is author of Flight inWinter, published by the Princeton University Press in 1942, the story of the outnumbered but heroic Serbian Army in World War I.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1946 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleThe Show Went On In Spite of Wartime Setbacks

June 1946 By HENRY WILLIAMS, -

Article

ArticleA Hard Job of Education A Hard Job of Education

June 1946 By JOHN W. FINCH -

Article

ArticleThe Truth About China

June 1946 By WING-TSIT CHAN, -

Article

ArticleRussia and the United States

June 1946 By OLIVER J. FREDERIKSEN '16 -

Article

ArticleOur Latin-American Foreign Policy

June 1946 By VICTOR G. BORELLA '30

Article

-

Article

ArticleFOOTBALL

December, 1919 -

Article

ArticlePOETRY SOCIETY FORMED

February 1921 -

Article

ArticleJumping M.D.

June 1944 -

Article

ArticleAt the Border of Hungary

January 1957 -

Article

Article"It is this combination of fine competition and emphasis on scholarship that has made Ivy competition a matter of pride for all of us."

JUNE 1973 -

Article

ArticleFever and Febrifuge

April 1949 By John Hurd '21.