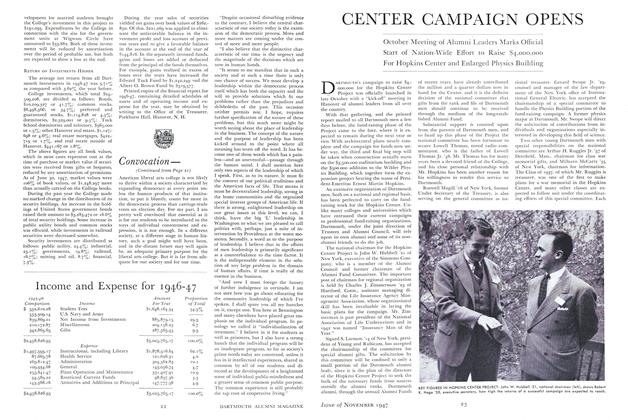

THE PROBLEM OF making ends meet is almost universal in periods of rapidly rising prices, but nowhere is it of greater concern than in the case of endowed institutions. A comparison of Dartmouth's postwar and prewar expenses, and a brief analysis of the manner in which these increased costs have been financed may therefore be of interest. Let us contrast the figures for the academic year 1940-1941, the last full prewar year, with those for the recently completed 1946-1947 period.

The total outlay for educational purposes for the postwar year was 53 per cent higher than in the prewar year. While categories for accounting purposes must of necessity be somewhat arbitrary, they nevertheless usually provide highly useful classifications. The expense classification known as "Instructional, including Libraries," for example, comprised about two-thirds of the college's educational costs in both the prewar and postwar periods. Expenditures charged to this classification, however, were 51 per cent greater in the later period. The other major expense categories are "Administration" and "General Plant Operation and Maintenance," and they increased by 49 per cent and 72 per cent respectively. These increases can be explained for the most part by higher wages and higher cost of supplies.

Throughout the nation considerable interest has been shown recently in the remuneration of the teaching profession. Accordingly a few words concerning the faculty seem appropriate. The size of the Dartmouth faculty was approximately the same in the two years being compared, in spite of a considerably larger enrollment in the latter period. However, there has been a change in the composition of the teaching staff. The number of professors has been increased by approximately the same amount as the decrease in number of those holding the rank of instructor. The number of assistant professors has remained about the same. This has been a fairly universal development, and has resulted from the interruption of graduate training caused by the war. The average remuneration of professors at Dartmouth has increased by about one-third in the period under consideration, and the average stipend of assistant professors has increased around 40 per cent. The instructorship is the only rank which has kept up with the cost of living, and receives an average salary that is almost 60 per cent more than prewar. Inasmuch as the average remuneration received by instructors was less than $2000 per annum in the 1940-1941 period this adjustment has been highly desirable. The foregoing should indicate that Dartmouth has made a strenuous effort to take good care of its faculty in a period of rapid price increases. The fact that raises have not generally kept up with living costs and the fact that many institutions with comparable standards have higher salary scales both emphasize the need for additional revenue.

How HAS THE College financed these increased expenditures? In spite of a decrease from approximately 3.9 per cent to about 3.7 per cent in the average net rate of return, after adjustments, from all investments, the total income from investments increased from around $706,000 to almost $886,000. This was made possible by an increase of 26 per cent in funds functioning as endowments, which now amount to more than $24,639,000. The larger enrollment and higher tuition have raised gross receipts from students by 52 per cent. Inasmuch as G. I. benefits have temporarily reduced the need for scholarship aid, the receipts from student fees net of these grants is up over 69 per cent. These increased receipts, however, were not sufficient to cover the increased expenditures which the-College was required to make. The larger deficit for the academic year just closed was met by the more generous support provided by the Alumni Fund.

The ultimate solution (if there is one) to the financial problems of the College poses additional difficulties, some of which have been implied by the foregoing discussion. Here are a few more of the perplexing problems. What will be the future course of prices? What would additional inflation mean to the College? Depreciation allowances which may have been quite adequate in the prewar period may be insufficient if replacements have to be made at considerably higher prices, to mention only one expense item. What hope is there for a levelling off of the price curve, and what would a decline in prices mean in terms of college costs? What effect would such a decline have on business profits upon which Dartmouth relies for dividends? (More than one-third of the College's investments are in common stocks.) What will the effect of a return to a smaller student body be on revenue and on costs? What will the termination of G. I. benefits involve in the way of additional scholarship aid?

To what extent can the endowed colleges and universities of the nation raise their charges without running the danger of becoming institutions exclusively for the education of the sons of wealthy men, unless such increased charges are offset by the availability of more student aid? Will the endowed colleges and universities be able to provide even the sons of the well-to-do with as well rounded an education if enrollment is so restricted? Will the endowed schools be fulfilling their entire obligation in a democratic society in such an eventuality?

A solution to these problems that is frequently suggested is for the federal government to provide financial assistance to the endowed institutions. Such assistance would go beyond the tax exemptions now enjoyed and envisages the granting of funds. But this solution involves the problem of whether such assistance can be administered so as to safeguard the public purse from wasteful grants without at the same time producing bureaucratic controls that would interfere with the academic freedom of the recipient institutions. An acceptable solution may be federal scholarships available to all high school graduates who pass qualifying examinations, and who may then freely choose their alma maters from a list of approved institutions. This is similar to the present method of handling G. I. educational benefits.

These considerations, however, lead us far afield and are properly the subject for more extended discussion than space here permits. Suffice it to say that making ends meet is a very real problem for endowed educational institutions and threatens to remain an urgent problem for the forseeable future. Until this problem is finally solved Dartmouth must continue to rely on the generosity of her alumni. She is indeed fortunate to possess, in unparalleled measure, the support of such an understanding group.

ASST. PROF. OF ECONOMICS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWHAT IS A GREAT ISSUE ?

November 1947 By ARCHIBALD MACLEISH, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1947 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

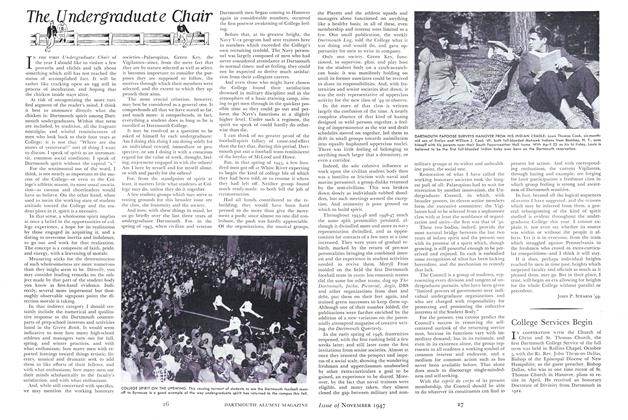

ArticleThe, Undergraduate Chair

November 1947 By JOHN P. STEARNS '49. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

November 1947 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

November 1947 By DONALD G. MIX, ROBERT M. MACDONALD -

Article

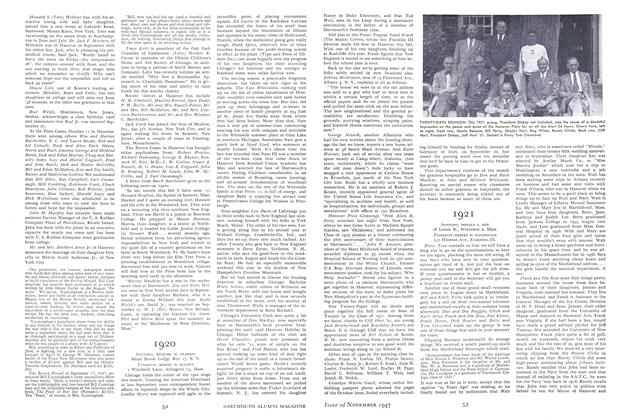

ArticleCENTER CAMPAIGN OPENS

November 1947

DANIEL MARX JR. '29,

Article

-

Article

ArticleJune Reunions

November 1946 -

Article

ArticleArthur R. Upgren Named New Dean of Tuck School

February 1953 -

Article

ArticleHonored for Public Service

October 1954 -

Article

ArticleThe Final Standings

SEPTEMBER 1998 -

Article

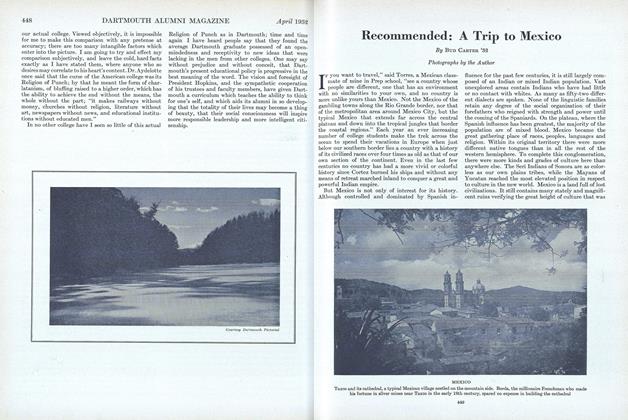

ArticleRecommended: A Trip to Mexico

APRIL 1932 By Bud Carter '32 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

February 1954 By HERBERT F. WEST '22