THE PROBLEM of who shall go to college may, as a result of the appearance of the first two volumes of the report of the President's Commission on Higher Education, now be deliberated by the entire populace and not reserved as a hair-shirt exclusively for the sorely harassed directors of admission. For the benefit of those who may have missed the story in the press, the first two volumes of the six-volume report on Higher Education for American Democracy (at the time of writing, four volumes are -still to be released) are entitled Establishingthe Goals and Equalizing and Expanding Individual Opportunity, and they contain the major outlines of the program.

Few readers of this publication will in all probability question the goals of the Commission to bring to all the people of the Nation education "for a fuller realization of democracy, ... for international understanding and cooperation, ... for the application of creative imagination and trained intelligence to the solution of social problems and to the administration of public affairs." Few readers will challenge the objective that "the American people should set as their ultimate goal an educational system in which at no level—high school, college, graduate school, or professional school—will a qualified individual in any part of the country encounter an insuperable economic barrier to the attainment of the kind of education suited to his aptitudes and interests," although we may entertain different notions as to what constitutes a qualified individual. The vast extent of the waste of human resources, however, is not as widely known as it should be. In spite of the importance of heredity, ability has an uncanny disregard for the environment in which it chooses to be born; and the life expectancy of democracy is not improved by the fact that only 53 per cent of the voters—people over twenty years of age—have completed more than an eighth-grade education. Not many readers will care to debate the Commission's contention that higher education can be improved so as to offer better preparation for adult life and to be of greater interest to students of varying aptitudes, intelligence and talents.

Greater differences of opinion, however, are apt to occur in regard to the Commission's program for achieving these objectives than in the definition of the goals themselves. The program calls for an improved high school education for all normal youth; education through the fourteenth grade available to all qualified students who choose to attend community junior colleges; federal and state financial assistance from the tenth through fourteenth grades to competent students who would not be able to continue their education without such aid; financial assistance to qualified students needing it to enable them to attend senior colleges and graduate or professional schools; a considerable expansion in adult education; and the equal accessibility of public education to all without regard to race, creed, sex or national origin.

The Commission estimates that 49 per cent of the population has the mental ability to complete fourteen years of properly designed schooling and that 32 per cent has the ability to complete an advanced liberal or professional education. The Commission believes that by 1960 a minimum of 4,600,000 young people (approximately twice the 1947 enrollment) should attend non-profit institutions for education beyond the twelfth grade. Of these, 2,500,000 would be on the junior college level, 1,500,000 on the senior college level (junior and senior years), and 600,000 in graduate and professional schools. To implement this program the Commission recommends a federal scholarship program for necessitous, qualified nonveterans similar in operation to the G.I. educational benefits. It suggests that the maximum scholarship per undergraduate might be $800 per annum and the average scholarship $400 per year. A limited number of graduate fellowships carrying $1500 per annum are also proposed. The entire federal scholarship and fellowship aid program is expected to cost about $1,000,000,000 annually by i960.

The implications of these recommendations are vast and many of them can only be considered after the remaining four volumes of the survey are released. However, some questions come to mind that warrant discussion at this time.

For example, the problem of tactics emerges immediately. \While it is true that the area of responsibility delimited in the presidential directive creating the Commission limited it to higher education, the question of whether the appropriate starting place should be the apex or the base of the educational pyramid remains undecided. Beyond a few passing references to high school education the Commission has not concerned itself with pre-college training which of necessity is basic to all that follows. Perhaps it is expected that the advantages of better and more general college training will permeate the lower schools in the future as teaching and home environment benefit from the anticipated progress in higher education. Nonetheless, our elementary and secondary school problem is far from being completely and satisfactorily solved and probably will remain unsolved until adequate remuneration is the rule rather than the exception. It would be unfair to criticize the present Commission for neglecting this problem which is clearly outside its jurisdiction, but one cannot help wondering what financial aid the precollege system requires when one is considering the fiscal demands of a program for higher education of the magnitude that has been proposed. However a discussion of these pecuniary problems should properly await the release of the Commission's fifth volume on FinancingHigher Education.

Another debatable question is what shall be the qualifications for college enrollment. Even if we were to grant the validity of the Commission's basis for selection and agree that higher education could be arranged to fit the needs and aptitudes of a larger number of students, several serious implications remain. The Commission has based its estimates on the criterion of how many can complete the courses of study involved and not on what we believe to be the more appropriate standard of how many can benefit from the program sufficiently to warrant the cost of providing it. Not many students of college age share the enthusiasm of the Marquess of Halifax when he said, "The struggling for knowledge hath a pleasure in it like that of wrestling with a fine woman." It is probably too much to hope that curricular reforms will provide all of the needed appeal. ,

Let us face candidly the well known fact that many graduates from college—any college—merely take pass degrees in both curricular and non-curricular activities. Many college enrollees derive little from their exposure to higher education beyond some dubious sartorial elegance and a few amiable social graces. As a British banker said some sixty-odd years ago, "The important thing is not so much that every child should be taught, as that every child should be given the wish to learn." In short the multriplication of mediocrity will equal neither ability nor purposefulness.

Of course the writer cannot help but be interested in some of the economic aspects of the plan. Some financial matters have already been alluded to. Of considerable economic importance is the fact that attendance at school is both a way of spending income and keeping men and women off the labor market. Furthermore education contributes to higher levels of production per worker. Therefore, such a program as that recommended by the President's Commission has implications not only for the longrun productivity of the nation, but also for the maintenance of high levels of consumers' expenditures and employment.

The Commission's emphasis on the need for social research and its comments on general education are very well taken indeed and deserve more attention than space here permits. The effect of the proposals on the four-year liberal arts college also deserves extended consideration.

The foregoing comments are not intended as carping criticism, and furthermore should not be interpreted as hostile to the objectives sought by the Commission. Economic disabilities and the accident of residence play an excessively large part in determining who goes to college. Nor has it been our intention to disparage American higher education. Both European and native scholars who have had an opportunity to make comparisons have marveled at its breadth and profundity and have sought an explanation for its comparative success in the broadness of its base. Furthermore, another fact remains, which is, that to learn to live the democratic way of life in the contemporary world is more complicated and requires more training for the majority of people than is necessary for them in order to earn the wherewithal for such a living. In the words of the Commission, "We may be sure our democracy will not survive unless American schools and colleges are given the means for improvement and expansion. This is a primary call upon the Nation's resources. We dare not disregard it. America's strength at home and abroad in the years ahead will be determined in large measure by the quality and the effectiveness of the education it provides for its citizens."

An appropriate solution will undoubtedly require an extension of community junior colleges to provide terminal general education for an enlarged number of students, and many of the Commission's recommendations regarding the senior colleges and graduate schools are undoubtedly necessary. Nevertheless while we might agree with Bacon and our own Black Dan'l that "knowledge is power," let us not neglect Montaigne's admonition that "It is not the business of knowledge to enlighten a soul that is dark of itself, nor to make a blind man to see. Her business is not to find a man's eyes, but to guide, govern and direct his steps, provided he has found feet and straight legs to go upon."

In short, the problem is even more extensive than the solution proposed by the President's Commission. We must not only provide facilities and financial aid but straight feet and legs to go upon.

ASST. PROF. OF ECONOMICS

Editorial comment on Volume 3 of theCommission's report, dealing with the organization of education, is being preparedby Prof. Hugh Morrison '26 of the MAGAZINE'S editorial board and will appear nextmonth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleATOMIC ENERGY CONTROL

February 1948 By CHESTER I. BARNARD, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

February 1948 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1948 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

February 1948 By H. REGINALD BANKART JR., FREDERICK T. HALEY, ROBERT W. NARAMORE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

February 1948 By A. W. LAUGHTON, WILLIAM H. SCHULDENFREI, ERNEST H. MOORE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1924

February 1948 By JAMES T. WHITE, RICHARD A. HENRY, DONALD E. COYLE

DANIEL MARX JR. '29,

Article

-

Article

ArticleA Prize Dartmouth Song

November, 1910 -

Article

ArticleOklahomans Honor Dean

March 1934 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

January 1939 -

Article

ArticlePREVIEW

September | October 2013 -

Article

ArticleIt All Began in Hanover

April 1951 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25 -

Article

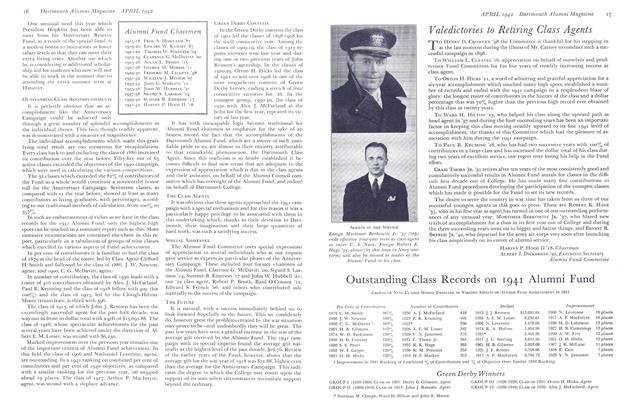

Article25th Anniversary Campaign Set New Records

April 1942 By HARVEY P. HOOD II '18