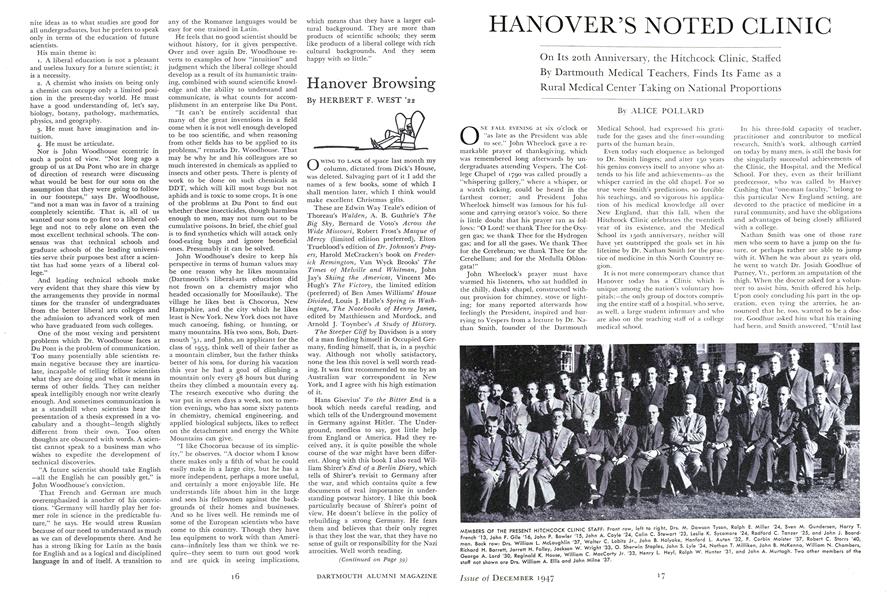

On Its 20th Anniversary, the Hitchcock Clinic, Staffed By Dartmouth Medical Teachers, Finds Its Fame as a Rural Medical Center Taking on National Proportions

ONE FALL EVENING at six o'clock Or "as late as the President was able to see," John Wheelock gave a remarkable prayer o£ thanksgiving, which was remembered long afterwards by undergraduates attending Vespers. The College Chapel of 1790 was called proudly a "whispering gallery," where a whisper, or a watch ticking, could be heard in the farthest corner; and President John Wheelock himself was famous for his fulsome and carrying orator's voice. So there is little doubt that his prayer ran as follows: "O Lord! we thank Thee for the Oxygen gas; we thank Thee for the Hydrogen gas; and for all the gases. We thank Thee for the Cerebrum; we thank Thee for the Cerebellum; and for the Medulla Oblongata!"

John Wheelock's prayer must have warmed his listeners, who sat huddled in the chilly, dusky chapel, constructed without provision for chimney, stove or lighting; for many reported afterwards how feelingly the President, inspired and hurrying to Vespers from a lecture by Dr. Nathan Smith, founder of the Dartmouth Medical School, had expressed his gratitude for the gases and the finer-sounding parts of the human brain.

Even today such eloquence as belonged to Dr. Smith lingers; and alter 150 years his genius conveys itself to anyone who attends to his life and achievements—as the whisper carried in the old chapel. For so true were Smith's predictions, so forcible his teachings, and so vigorous his application of his medical knowledge all over New England, that this fall, when the Hitchcock Clinic celebrates the twentieth year of its existence, and the Medical School its 150 th anniversary, neither will have yet outstripped the goals set in his lifetime by Dr. Nathan Smith for the practice of medicine in this North Country region.

It is not mere contemporary chance that Hanover today has a Clinic which is unique among the nation's voluntary hospitals: —the only group of doctors comprising the entire staff of a hospital, who serve, as well, a large student infirmary and who are also on the teaching staff of a college medical school.

In his three-fold capacity of teacher, practitioner and contributor to medical research, Smith's work, although carried on today by many men, is still the basis for the singularly successful achievements of the Clinic, the Hospital, and the Medical School. For they, even as their brilliant predecessor, who was called by Harvey Cushing that "one-man faculty," belong to this particular New England setting, are devoted to the practice of medicine in a rural community, and have the obligations and advantages of being closely affiliated with a college.

Nathan Smith was one of those rare men who seem to have a jump on the future, or perhaps rather are able to jump with it. When he was about 21 years old, he went to watch Dr. Josiah Goodhue of Putney, Vt., perform an amputation of the thigh. When the doctor asked for a volunteer to assist him, Smith offered his help. Upon coolv concluding his part in the operation, even tying the arteries, he announced that he, too, wanted to be a doctor. Goodhue asked him what his training had been, and Smith answered, "Until last night I have labored daily with my hands."

If inferences may be made from his later actions, it was probably at this moment that Smith realized keenly not only his own inadequacy but the need for instruction in rural areas for all farm boys like himself who wanted to be doctors; and the Dartmouth Medical School was as good as founded. Smith obtained his own training for medicine at great sacrifice in time and effort; but he was destined never to be satisfied until he had passed on to others what he himself had won alone.

Another incident shows how Nathan Smith regarded the future as being mainly the repository of coming achievements. When he was convinced that Dartmouth was the place for training country doctors, he went to John Wheelock and the Trustees and asked them to consider founding a medical school. His suggestion was cordially received but Smith was told he would have to wait a year for the answer. Undismayed, he at once planned and embarked upon twelve months of study in Edinburgh and London, and while abroad bought books with his own money for a medical school library.

In Smith's sixteen years at Dartmouth he occupied, in the words of Oliver Wendell Holmes, "not a chair but a whole settee of professorships." He carried on a medical practice over a widespread rural area. While on the long horseback rides over the country roads, usually accompanied by a medical student whom he taught, Smith planned many of the articles that he would write later, in the uneven candlelight of a farm bedroom. It was said of him by Professor Knight of Yale: "Dr. Smith was more extensively known than any other medical man in New England, or indeed than any man in any profession."

It was Smith who wrested the funds for a medical school building from the State Legislature, and who himself donated the site of land on which to erect the building. When as a stipulation he was requested also to "assign to the State his Anatomical Museum and Chemical Apparatus" he agreed. Later in disappointment he wrote that this "was too much to give.... in sacrificing on the Esculapean altar."

Although Smith received many discouragements in Hanover, there is reason to believe that when he left Dartmouth he was also in part following his sense of where his greater usefulness would lie. He quit Hanover shortly before the tumultuous days that culminated in the Daniel Webster case; and after the age of 51 years, he helped found successively the medical schools of Yale, Bowdoin, and the University of Vermont. But he left behind him in Hanover more than the gratitude of students and patients, more than his land, and the hearty regret of Dartmouth. He left a daring and solid medical tradition, which still basically fulfills the needs of Hanover, the College, and the surrounding rural area.

He seems also to have bequeathed his saving sense of the future. At any rate a study of the history of the Mary Hitchcock Hospital, given in 1893 by Hiram Hitchcock in memory of his wife, and of the Hitchcock Clinic, now 20 years old, reveal this two-fold adaptation: a courage in contending with needs as they have arisen, and these have often been severe and discouraging; and the capacity to judge the outline of needs to come.

Hiram Hitchcock was praised for the generosity of his gift, but it was generally believed that this 38-bed "cottage-type hospital" was far too large for the community. However, after a slow start, the average daily occupancy rose steadily, almost alarmingly, considering the facilities. The present number of beds is 225, six times the original figure. In a ten-year span, from 1937 to 1946, annual admissions rose from 3361 patients to 4781. The average daily number of patients rose from 101 in 1937 to 171 in 1946.

Even with generous gifts—the addition of an X-ray unit in its own annex, a nurses' home, additional wards and doctors' offices—the physical limitations of the hospital have prevented its keeping pace with all the demands put upon it.

In addition, the doctors faced one great problem with which Nathan Smith never had to contend—the astonishing expansion of the science of medicine. Methods of transportation steadily improved from the days when the doctor left Hanover on horseback to the times when he went to outlying towns by train and then was met by wagon or sleigh. The automobile brought many more patients to the hospital, thus saving doctors miles of travel and hours of time; and today one member of the Hitchcock Clinic goes to outlying districts in his own plane. But even more rapid than the improvements in transportation was the fast-growing field of this science, breaking down into branches and specialties, in obstetrics, surgery, x-ray, anesthesia and medicine.

In 1927 there were five men on the staff of the Mary Hitchcock Hospital. Each had his own office at home or elsewhere, and conducted his practice and business affairs independently. Only the hospital ward patient had the benefit of treatment by all the doctors.

These five men faced a problem which they foresaw would become acute: ninety per cent of all the patients were from outside of Hanover. Between Boston and Montreal there was a great lack of medical service in specialized fields, and the resources of Hanover were being increasingly called upon. It was physically and mentally impossible for five doctors independently to begin to meet the needs of this area.

It was decided that with the hospital as the "hub of the wheel" the forming of a rural medical center or clinic, with coordination of personnel and equipment, would best meet the requirements of the situation. The hospital trustees agreed to the proposal, and a well-working arrangement between the hospital and the clinic staff of doctors has been the result. It is a joint lay-professional enterprise. Liaison between the Clinic and Hospital is accomplished by meetings of the Professional Staff representatives, the Executive Committee of the Trustees, and the Superintendent of the Hospital. All joint committees on policy, organization and administration are appointed by this group. The Clinic staff is composed of senior and junior members and associates. Each doctor studies part of the year at other medical centers, so that he may be able to keep up with the advances in his own specialty.

The forming of the Clinic has been of immeasurable benefit, in that it permits the doctor to give his time to the practice and study of medicine without the waste entailed in sending out bills, traveling long distances and expending funds in the expensive duplication of equipment. Each patient has the benefit of the combined knowledge of many doctors, and there are available to him types of equipment a private practitioner can seldom afford.

They are largely invisible from the Hanover Plain, but the farms and villages along the Upper Connecticut Valley have been vitally affected by Hanover and the College ever since the days when Eleazar Wheelock settled upon this strategic spot on the River. The inhabitants are known to be very independent in their judgments, however ungrudging they may be in acknowledging credit once it is established. It was not easy, in the early days of Hiram Hitchcock's gift, to convince them that coming to a hospital did not automatically mean that they would die there —unless they waited too long to come, which they all too frequently did. More than once a patient was operated on who lived in sight of the Mary Hitchcock Hospital but who refused to go any closer.

Later, when the Clinic was formed, many patients asked to be treated by only one or "my" doctor. Accustomed as they were to the understanding interest of a family physician, this was a natural desire. It is to the outstanding credit of the Clinic that it has worked so efficiently as a unit that the patient more and more has a sense of security, conveyed by the doctors' personal interest, and of the advantages of treatment by a group of specialists. The patient sees first the doctor for whom he asks, and it is the obligation of one staff member to consider the patient as a whole and to interpret all data gathered 'by the staff.

It is almost impossible for an openminded person not to see the advantages of such a clinic: the accident case who immediately receives the care of a medical man, a neurologist, a surgeon, if required, and an x-ray specialist; or the case that is not easily diagnosed without consultation; or the patient, a more frequent type than is realized, who has more than one thing the matter with him. A man may have a broken leg and diabetes, requiring the orthopedist and internist. Or he may be undergoing a disabling emotional difficulty requiring a psychiatrist, and suffer from real heart trouble as well, which necessitates another specialist. A polio victim is first seen by the orthopedist and neurologist; then, after the acute phase is past, the orthopedist and physiotherapist. All children, no matter what they have been brought in for, are placed under the care of the pediatrician, who works with the dermatologist, psychiatrist, internist, or whoever may be on the case.

Besides the patients whom they treat in the Hospital or at the Clinic, the staff has the responsibility of all the student and faculty cases in Dick's House. In addition, the Clinic doctors are all on the teaching staff of the Dartmouth Medical School.

In an essay by A. E. Clark-Kennedy, dean of the medical school in Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, he writes, "Every advance in medicine creates a new problem in medical practice, education and administration."

It is this three-fold obligation that the Hospital, the Clinic and the Medical School have endeavored to meet. The development of medicine in Hanover as elsewhere seems to lie in the direction of greater education, not only for doctors but for laymen, and as knowledge is made increasingly available, treatment becomes more and more a joint enterprise between doctor and patient.

Since the beginning, the Dartmouth Medical School has made its influence felt far beyond Hanover. Doctors come each fall from Boston, New York and other large cities to teach students and to observe cases" in Hanover. Until 1913, the School had a four-year course which at that time was reduced to two, mainly because of lack of clinical material for the students. Nevertheless, the demands upon the Hospital and the Medical School as teaching units have been vastly increased in recent years. At present there is maintained a vital cooperation between the Mary Hitchcock and other hospitals in the vicinity, in the fields of laboratory, medicine, radiology, and general consultation. The radiology and laboratory work of several outlying hospitals is weekly supervised by the Hospital, which also conducts four or more times a week seminars in pathology, urology, chest, cancer and anesthesia,—all open to visiting doctors, as are special lectures and consultations.

In July 1946, in keeping with the recent policies of the Veterans' Administration, the supervision of the 250-bed Veterans' Hospital at White River Junction was placed under the Dean's Committee of the Dartmouth Medical School. This provides further opportunity for the School's residency teaching, as well as advantages for the Veterans' Hospital.

Besides a rotating interne service which trains men for general practice and provides basic training for specialties, the Mary Hitchcock is the only institution within a large area conducting schools for x-ray, laboratory and anesthesia technicians. The School of Nursing is the largest in New Hampshire.

In line with this great expansion in the educational field, the Hitchcock Foundation was created in 1946, for the purpose of advancing the research fields of medicine and surgery. The investigation of problems of hygiene, health and public welfare, as well as definite research projects undertaken by members of the Clinic, fall under the jurisdiction of this Foundation. At present there are fifteen research projects in process, as well as plans for expansion in less specialized fields of medical education.

The patients who come to the Clinic and Hospital represent a surprisingly varied cross-section of society: they are college students (girls, too, who come down with measles on a weekend, or who try to ski for the first time at Carnival), alumni, housewives, businessmen, miners from the nearby copper mines, camp girls, workers from the mills, farmers, professors, well-to-do older people who have retired to the rural life, doctors' families, Dartmouth and high school athletes, and many other groups. And their ailments are almost as varied as they are.

Each time a new specialty has been added to the Clinic it has been feared that the need would not be great enough to keep the specialist busy; and in every case the need was far greater than anyone realized. There are now 30 members of the Clinic representing these 17 specialties: General Surgery, Gynecology, Neurosurgery, Orthopedic Surgery, Plastic Surgery, Thoracic Surgery, Internal Medicine, Ear, Nose and Throat and Bronchoscopy, Neurology, Psychiatry, Dermatology, Obstetrics, Ophthalmology, Pediatrics, Radiology, Anesthesiology and Urology.

Formerly the man who wanted to be a country doctor was almost forced, because of lack of scientific incentive in rural areas, to choose between his medical career and his preference for country life. Rural practice still makes up the body of American medicine. It is to an environment like Hanover, where well-trained men may live and practice a specialty, that doctors are returning—to areas where they are sorely needed. Even as Nathan Smith gained comfort and strength from his love of nature and hours spent outdoors, so there are many men today who are happiest and best suited to country practice.

If any man could have been a one-man clinic that one man would have been Dr. Nathan Smith. But even this "driving genius" could not have mastered all the complexities of modern medicine.

Perhaps if he could he would return to Hanover today more gladly than he left it 134 years ago—if he could see how his three interests, the learning, teaching and practice of medicine, have been expanded, and are being carried further along in the direction in which he always looked—the future.

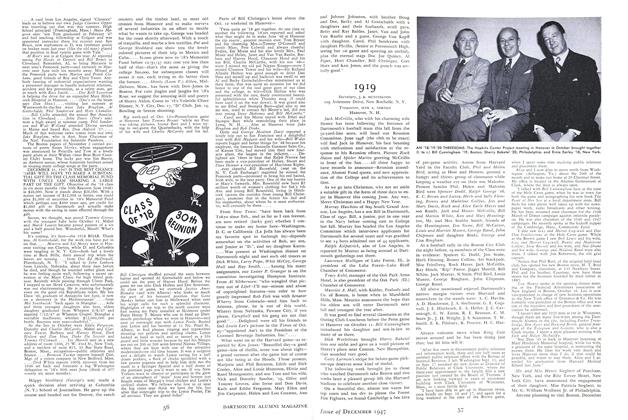

MEMBERS OF THE PRESENT HITCHCOCK CLINIC STAFF: FRONT ROW, LEFT to right, Drs. M. Dawson tyson, Ralph E. Miller '24, Dven M, Gundersen, Harry T. French '13, John F. Gile '16, John P. Bowler '15, John A. Coyle '24, colin C. Stewart '23, Leslie K. Sycamore '24, Radford C. Tonzer '25, and John J, Board. man. Back row: Drs. William L. Mclaughlin '37, Walter C. Lobitz Jr., John B. Holyoke, Hanford L. Auten '32, F. Corbin Moister '37, Robert C. Storrs '40, Richard H. Barrett, Jarrett H. Folley, Jackson W. Wright '33, O. Sherwin Staples, Lyle '34, Nathan T. Milliken, John B. Mckenna, William N. Chambers, George A. Lord '30, Reginald K. House, William C. MacCarty Jr. '33, Henry L. Heyl, Ralph W. Hunter '31, and John A. Murtagh. Two other members of the staff not shown are Drs. William A. Ellis and John Milne '37.

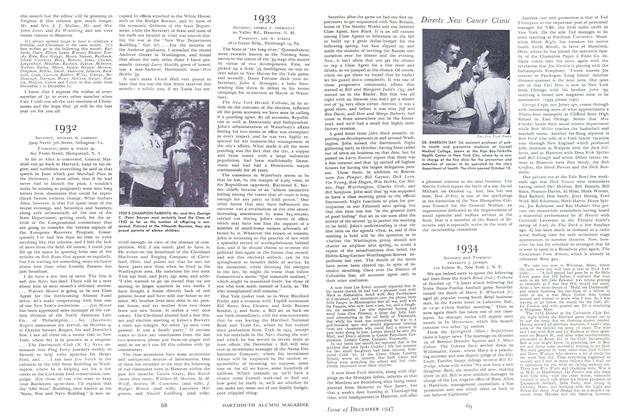

IN THE MAIN CLINIC OFFICE: Dr. Jackson W. Wright '33, one of the nine doctors specializing in internal medicine, checks over part of the Clinic's detailed record file with Miss Madeline Thill of the staff.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleMEN VS. MICROSCOPES

December 1947 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1947 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

December 1947 By KARL W. KOENIGER, DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

December 1947 By J. K. HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

December 1947 By FRANKLYN J. JACKSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1913

December 1947 By WARDE WILKINS, ROBERT O. CONANT

ALICE POLLARD

-

Article

ArticleThe Last Craftsman

JUNE 1930 By Alice Pollard -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S RIVER

June 1945 By Alice Pollard -

Article

Article"THE LOOSE-ENDERS"

January 1946 By ALICE POLLARD -

Article

Article"Pest House" Days

May 1948 By ALICE POLLARD -

Article

ArticleSheepskin Season Recalls a Mystery

June 1953 By Alice Pollard -

Article

ArticleNow It's Reunion Week

July 1955 By ALICE POLLARD

Article

-

Article

ArticleDANIEL WEBSTER'S OAK TREE GAINS PLACE IN HALL OF FAME

February 1921 -

Article

ArticlePROGRAM ANNOUNCED FOR COMMENCEMENT

JUNE, 1928 -

Article

ArticleWelcoming challenges

SEPTEMBER 1984 -

Article

ArticleTuck School

MARCH 1967 By JOHN ALLBEE T'61 -

Article

ArticleCinderental

MARCH 1990 By Kathryn McKenna '91 -

Article

ArticleThe College Days of Sherman Adams

May 1953 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29