FORTUNATE in possessing one of the best collections of diplomas in this country, the Dartmouth College Archives has sheepskins which range from two signed in 1775 and 1776 by Eleazar Wheelock and presented per auctoritatemnobis a Georgio Tertio, to the most recent, of 1951, which would have greatly puzzled Eleazar with its inclusion of the words "Senior Fellow." Like the rest of the world, these diplomas over the years reflect change. Yet even more eloquently they indicate the continuity of Dartmouth's durable tradition, which binds the past firmly to the present.

Some of the links with the past have been decidedly tangible. Even as late as 1939 the steel die, which was made by Nathaniel Hurd, an eminent engraver of Boston, and presented to Eleazar Wheelock by Trustee George Jaffrey in 1773, was used to impress the college seal on each individual sheepskin. Max Norton '19, College Bursar, well remembers wielding the hand press used for the purpose. There have been only two years in the history of the College when the seal did not appear on the diplomas, and that was from 1817 to 1819, when the "College Party" was fighting the "University Party" and the latter had seized the seal and college buildings. The Latin words on the diplomas have been substantially the same, even though today the modern graduate, who is generally unversed in the Classics, can read a translation posted for his convenience by the Dean of the College on the bulletin board in Parkhurst.

"Furnished at the expense of the graduates," the early diplomas were printed and embellished by hand by friends, relatives or classmates. The seal was fixed upon a separate piece of parchment and attached to the diploma by a ribbon. After 1876 the seal was pressed directly on the diploma.

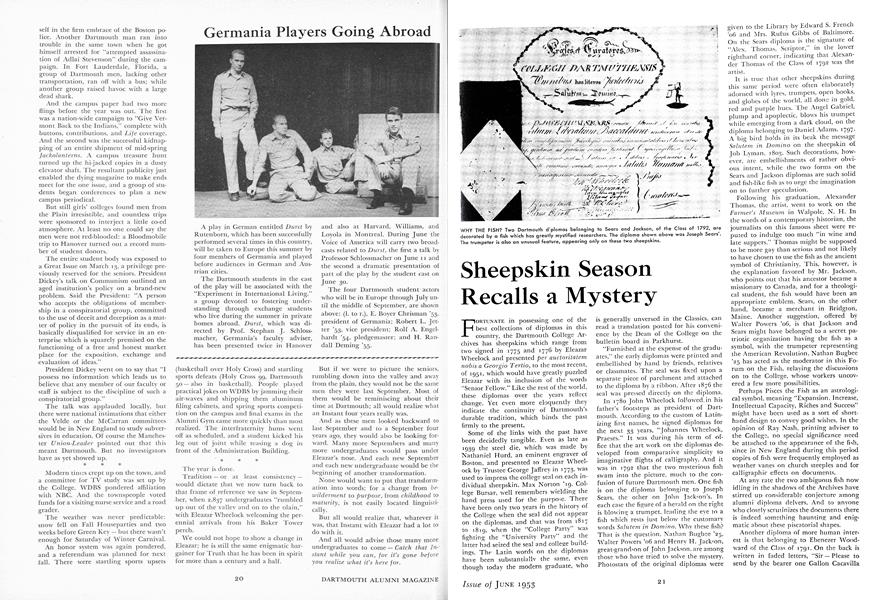

In 1780 John Wheelock followed, in his father's footsteps as president of Dartmouth. According to the custom of Latinizing first names, he signed diplomas for the next 33 years, "Johannes Wheelock, Praeses." It was during his term of office that the art work on the diplomas developed from comparative simplicity to imaginative flights of calligraphy. And it was in 1792 that the two mysterious fish swam into the picture, much to the confusion of future Dartmouth men. One fish is on the diploma belonging to Joseph Sears, the other on John Jackson's. In each case the figure of a herald on the right is blowing a trumpet, leading the eye to a fish which rests just below the customary words Salutem in Domino. Why these fish? That is the question. Nathan Bugbee '25, Walter Powers '06 and Henry H. Jackson, great-grandson of John Jackson, are among those who have tried to solve the mystery. Photostats of the original diplomas were given to the Library by Edward S. French '06 and Mrs. Rufus Gibbs of Baltimore. On the Sears diploma is the signature of "Alex. Thomas, Scriptor," in the lower righthand corner, indicating that Alexander Thomas of the Class of 1792 was the artist.

It is true that other sheepskins during this same period were often elaborately adorned with lyres, trumpets, open books, and globes of the world, all done in gold, red and purple hues. The Angel Gabriel, plump and apoplectic, blows his trumpet while emerging from a dark cloud, on the diploma belonging to Daniel Adams, 1797. A big bird holds in its beak the message Salutem in Domino on the sheepskin of Job Lyman, 1803. Such decorations, however, are embellishments of rather obvious intent, while the two forms on the Sears and Jackson diplomas are such solid and fish-like fish as to urge the imagination on to further speculation.

Following his graduation, Alexander Thomas, the artist, went to work on the Farmer's Museum in Walpole, N. H. In the words of a contemporary historian, the journalists on this famous sheet were reputed to indulge too much "in wine and late suppers." Thomas might be supposed to be more gay than serious and not likely to have chosen to use the fish as the ancient symbol of Christianity. This, however, is the explanation favored by Mr. Jackson, who points out that his ancestor became a missionary to Canada, and for a theological student, the fish would have been an appropriate emblem. Sears, on the other hand, became a merchant in Bridgton, Maine. Another suggestion, offered by Walter Powers '06, is that Jackson and Sears might have belonged to a secret patriotic organization having the fish as a symbol, with the trumpeter representing the American Revolution. Nathan Bugbee '25 has acted as the moderator in this Forum on the Fish, relaying the discussions on to the College, whose workers uncovered a few more possibilities.

Perhaps Pisces the Fish as an astrological symbol, meaning "Expansion, Increase, Intellectual Capacity, Riches and Success" might have been used as a sort of shorthand design to convey good wishes. In the opinion of Ray Nash, printing adviser to the College, no special significance need be attached to the appearance of the fish, since in New England during this period copies of fish were frequently employed as weather vanes on church steeples and for calligraphic effects on documents.

At any rate the two ambiguous fish now idling in the shadows of the Archives have stirred up considerable conjecture among alumni diploma del vers. And to anyone who closely scrutinizes the documents there is indeed something haunting and enigmatic about these piscatorial shapes.

Another diploma of more human interest is that belonging to Ebenezer Woodward of the Class of 1791. On the back is written in faded letters, "Sir Please to send by the bearer one Gallon Cacavilla wine and Charge it my account." A diploma as a means for identification was undoubtedly effective but considerably more bulky than a present-day driver's license.

Dartmouth is one of the few colleges which still hands diplomas in person to its graduates. Now that the classes are so large, this requires two weeks of preparation by the Dean's Office. Until 1947 each diploma was of sheepskin, which was shipped from England. Following the war sheepskin was impossible to obtain in quantity and heavy bond paper has been used since. One long-time tradition still holds: the name of each graduate is printed in by hand. This has been done.since 1923 by Arthur Barwood, manager of The Nugget.

In August 1771 Eleazar Wheelock welcomed Governor Wentworth, servant of the Crown, and other distinguished visitors to the College's first graduation exercises. This June the President of the United States will be present at Dartmouth's Commencement 182 years later. The words on the diplomas ,of the Class of 1953 will be substantially the same as those on the sheepskins of the first four alumni of the College. Translated by Wm. Stuart Messer, Daniel Webster Professor of the Latin Language and Literature, the diplomas read:

The Trustees of Dartmouth College

To all who read, this document greetings in the Lord:/Be it known that it has been decided to honor and in accord with his merits/To decorate (him) with the title and grade of Bachelor of Arts and that we have bestowed upon him the fullest power/Of enjoying all the privileges and immunities and honors which everywhere on earth/Pertain to this same grade. Of which act let our official seal and names be for a witness./ Conferred from the academic halls in Hanover in New Hampshire on the day/Of the month of June in the year of the salvation of mankind-.

EXPERIENCED: Arthur C. Barwood, manager of The Nugget, who has hand-lettered the names on Dartmouth diplomas for the past thirty years.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1953 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleTHE YEAR IN REVIEW

June 1953 By RICHARD C. CAHN '53, UNDERGRADUATE EDITOR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

June 1953 By PHILIP K. MURDOCH., MARVIN L. FREDERICK -

Article

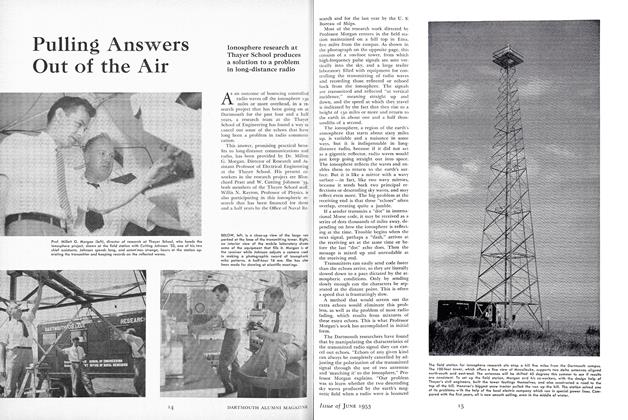

ArticlePulling Answers Out of the Air

June 1953 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

June 1953 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

June 1953 By JOHN A. WRIGHT, JAMES D. CORBETT

Alice Pollard

-

Article

ArticleThe Last Craftsman

JUNE 1930 By Alice Pollard -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S RIVER

June 1945 By Alice Pollard -

Article

Article"THE LOOSE-ENDERS"

January 1946 By ALICE POLLARD -

Article

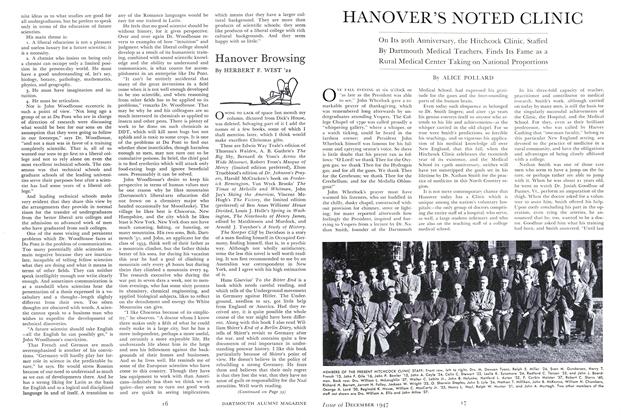

ArticleHANOVER'S NOTED CLINIC

December 1947 By ALICE POLLARD -

Article

Article"Pest House" Days

May 1948 By ALICE POLLARD -

Article

ArticleNow It's Reunion Week

July 1955 By ALICE POLLARD