I hope it won't sound pretentious to say that I was born a screenwriter, but it would be difficult to deny that I came by it naturally. My father, B.P. Schulberg, had been one of the early screenwriters, writing photoplays (as they were called then) for Edwin S. (Great Train Robbery) Porter before he was old enough to vote. By the time I started grammar school in Hollywood, B.P. was running his own, small independent film company, sharing the now-forgotten Mayer-Schulberg Studio with mogul-to-be L.B.

The year I entered Los Angeles high school, 1928, when my old man had been running Paramount Studios for several years, the first Best Picture Academy Award went to his film Wings, and his foreign import, Emil Jannings, was voted Best Actor for The Way of All Flesh.

Through my high school years, story conferences in the library after dinner were part of our family routine. Father coped with the movie stars, but his heart was with the writers, and I was privileged to sit in on crash writing sessions with some of Hollywood's best Herman Mankiewicz, Vincent Lawrence, young Joe Mankiewicz, Edwin Justus Mayer. Long into the night they hammered out story lines and debated characters' motivations. On weekends, if a screenwriter had fallen down badly, I would work on the delinquent script with my father, who could write a pretty fair scene to his dying day.

One of B.P.'s most gifted assistants was David O. Selznick, whose career would be crowned by Gone with the Wind. In the summer before I entered Dartmouth, David had left Paramount to become the 30-year-old head of R.K.O. One Sunday afternoon at our Malibu Beach house I told David a story idea I was working on about a little black boy whose mother is a cook on the estate of a wealthy white family with a son the same age as hers. Titled, none too originally, "Stay in Your Own Backyard," it was a sentimental little tale of comradeship between the two boys, the white kid teaching the black one to swim in his pool, and you guessed it the black boy giving his life to save his white chum from drowning. At the fade-out, the bereaved mother (Hattie McDaniels) holds her lifeless little boy in her arms and sings, "Stay in Your Backyard."

B.P. had turned out a "hit" movie in Skippy with Jackie Cooper and Bobby Coogan, and David thought he smelled a likely follow-up. He not only bought my little yarn for $1,500 but hired me to adapt it with an older collaborator, the mysterynovel writer Stewart Palmer. When I arrived at Middle Fayerweather I somewhat ostentatiously displayed a framed photo of Selznick's check on the wall of my room in the dorm.

Graduating in 1936, when F.D.R. and the New Deal were still seeking new cures for unemployment, I was one of the lucky ones who had a nice job waiting for him in Hollywood, in Dave Selznick's story department, earning what seemed then a rather ample $50 a week. Six months later I graduated to junior writer at $75. Junior writer might be described as pinch hitter pulled in from the bench at opportune moments.

On the original A Star is Born, directed by B. P.'s discovery William Wellman and largely written by Dorothy Parker and her husband Alan Campbell, I came up with an idea for the final scene and got credit (along with Ring Lardner Jr.) for "Additional Dialogue." When Ben Hecht walked out on his flamboyant Carol Lombard-Freddy March film Nothing Sacred, Ring and I were rushed in to save it. That may sound exciting, but after a year or so of patchwork assignments, I asked David Selznick not to pick up my option for another year at $ 100 a week. He was annoyed with me, saying he had hoped to carry me as a writer long enough to prepare me to assist him in production as he had assisted my father. His sense of Hollywood hierarchy and "royal succession" was very deep. When I told David I didn't want to be "carried as a writer" I wanted to write, he frowned and said his plan had been to keep me there long enough for my "producer's blood" to assert itself. In time, that anecdote would find its way into Scott Fitzgerald's Hollywood novel, The LastTycoon.

Free of my seven-year contract, I went to work for Walter Wanger on the now legendary if not notorious WinterCarnival. When my script faltered, Walter brought in Scott Fitzgerald, a glorified but now somewhat tarnished pinch-hitter. Scott and I made a near-fatal journey to the actual Winter Carnival that ten years later I would use'as the spine of my novel TheDisenchanted. After a bibulous two days in Hanover, Scott and I were both fired and virtually run out of town. In New York, Walter rehired me, replacing Scott with my boyhood friend Maurice Rapf, who labored on the picture with me to the end.

Written piecemeal, inevitably the picture was a mess, though somehow it seems to have improved with age. Only last week, it was shown in London at the National Film Theatre, where I lectured on the role of the film writer. It was the humiliating condition of the writer in Hollywood that in 1939—40 drew me back to Norwich and Hanover, where I wrote my first novel, What Makes Sammy Run?

The succes scandale of that novel helped to free me from economic and emotional dependence on Hollywood. The films I made with Elia Kazan in the fifties-Onthe Waterfront and A Face in the Crowd- were written and shot entirely in the East. Even though the writer is still the low man (or woman) on the Hollywood totem, I've, never lost my enthusiasm for film writing, only for living in Hollywood. My years at Dartmouth as an undergraduate and afterwards literally changed my life. For the rest of my days, Hollywood would continue to fascinate me but preferably from afar.

Undergraduate Schulberg with producer Wanger

Budd Schulberg'36, novelist and screenwriter, livesin Westbampton Beach, New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

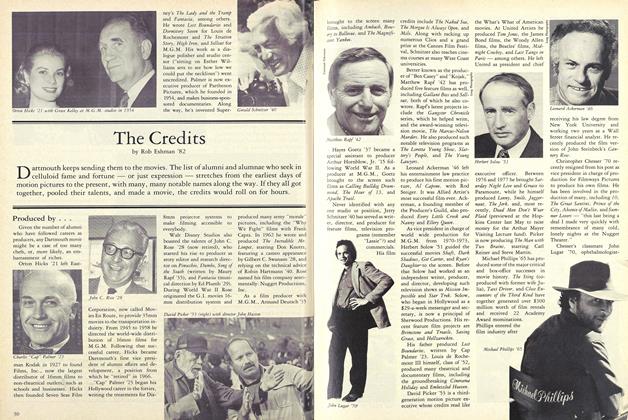

FeatureThe Credits

November 1982 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureThe Hollywood Connection

November 1982 By Maury Rapf '35 -

Feature

FeatureEvaluating Kitsch

November 1982 By Alan Gaylord -

Feature

FeatureHelping Sammy Run

November 1982 -

Feature

FeatureThe Camera Man

November 1982 By James Farley '42 -

Feature

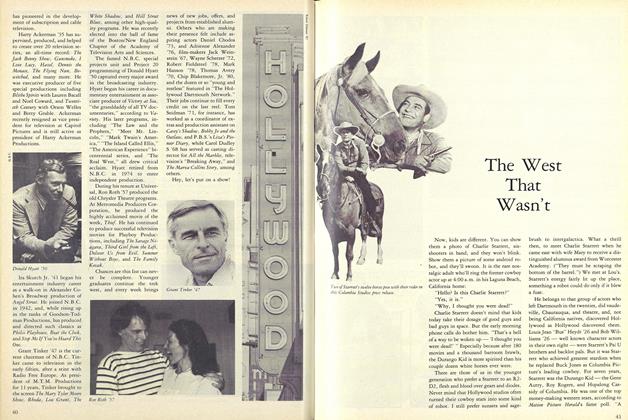

FeatureThe West That Wasn't

November 1982 By R.E.

Budd Schulberg '36

Features

-

Feature

FeatureMovie Maker

OCTOBER 1966 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Inauguration

NOVEMBER 1998 -

Feature

FeatureMan and His Environment

JUNE 1971 By ALVIN O. CONVERSE -

Cover Story

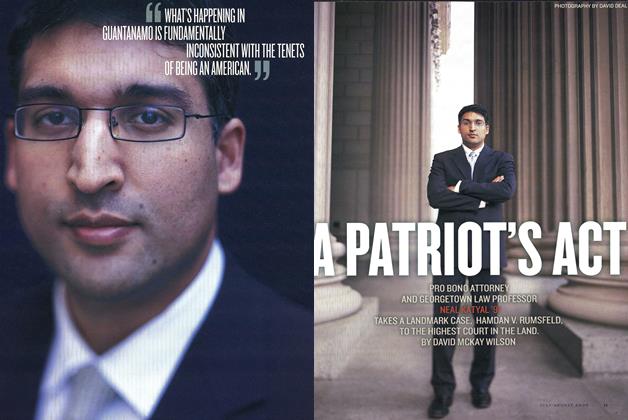

Cover StoryA Patriot’s Act

July/August 2006 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Cover Story

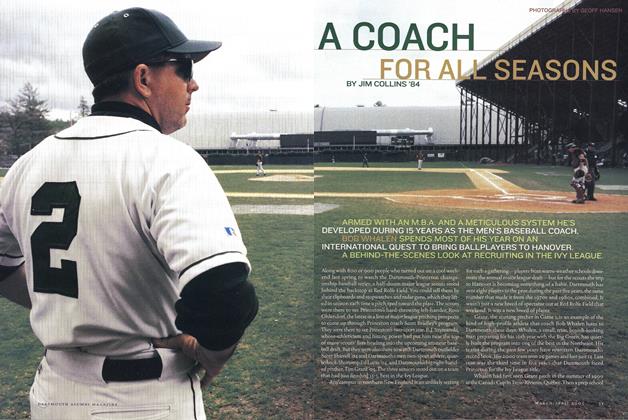

Cover StoryA Coach For All Seasons

Mar/Apr 2005 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

FeatureThe Uncompetitive Society

MAY • 1987 By Richard D. Lamm