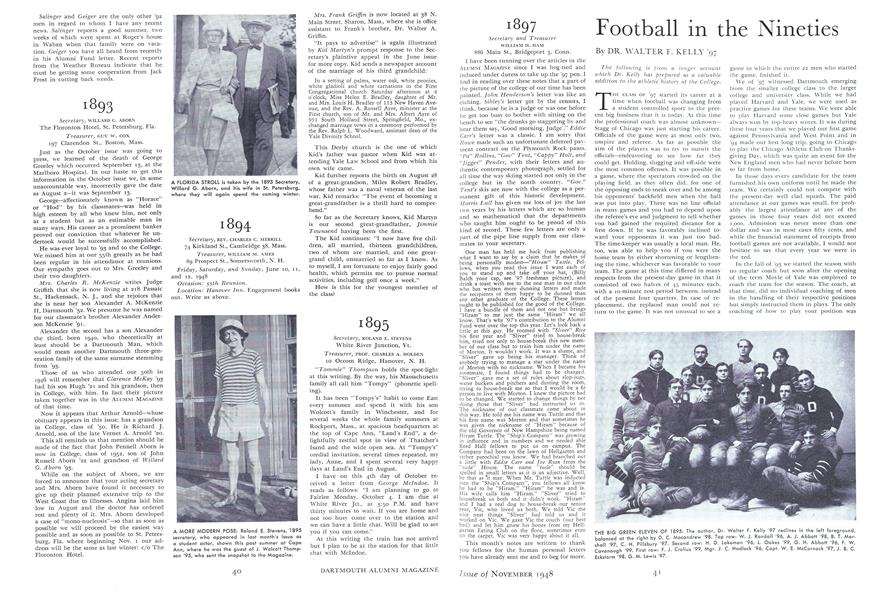

The following is from a longer accountwhich Dr. Kelly has prepared as a valuableaddition to the athletic history of the College.

THE CLASS OF '97 started its career at a time when football was changing from a student controlled sport to the present big business that it is today. At this time the professional coach was almost unknownStagg of Chicago was just starting his career. Officials of the game were at most only two, umpire and referee. As far as possible the aim of the players was to try to outwit the officials—endeavoring to see how far they could get. Holding, slugging and off-side were the most common offenses. It was possible in a game, where the spectators crowded on the playing field, as they often did, for one of the opposing ends to sneak over and be among his opponents' backfield men when the ball was put into play. There was no line official in many games and you had to depend upon the referee's eye and judgment to tell whether you had gained the required distance for a first down. If he was favorably inclined toward your opponents it was just too bad. The time-keeper was usually a local man. He, too, was able to help you if you were the home team by either shortening or lengthening the time, whichever was favorable to your team. The game at this time differed in many respects from the present-day game in that it consisted of two halves of 45 minutes each, with a 10-minute rest period between, instead of the present four quarters. In case of replacement, the replaced man could not return to the game. It was not unusual to see a game in which the entire 22 men who started the game, finished it.

We of '97 witnessed Dartmouth emerging from the smaller college class to the larger college and university class. While we had played Harvard and Yale, we were used as practice games for these teams. We were able to play Harvard some close games but Yale always won by top-heavy scores. It was during these four years that we played our first game against Pennsylvania and West Point and in '94 made our first long trip, going to Chicago to play the Chicago Athletic Club on Thanksgiving Day, which was quite an event for the New England men who had never before been so far from home.

In those days every candidate for the team furnished his own uniform until he made the team. We certainly could not compete with the present-day well clad squads. The paid attendance at our games was small, for probably the largest attendance at any of the games in those four years did not exceed 1,000. Admission was never more than one dollar and was in most cases fifty cents, and while the financial statement of receipts from football games are not available, I would not hesitate to say that every year we were in the red.

In the fall of '93 we started the season with no regular coach but soon after the opening of the term Moyle of Yale was employed to coach the team for the season. The coach, at that time, did no individual coaching of men in the handling of their respective positions but simply instructed them in plays. The only coaching of how to play your position was given by the older members of the team. Perhaps a good idea of what the man was up against can be illustrated in my own case. I had been playing in the backfield on the second team and was transferred to end on the varsity, a position I had never played, given about ten minutes' practice in going through signals and taken the next day to New Haven to play end against Yale. The only instructions given me were to tackle hard and be careful not to get "sucked in."

The fall of '93 saw the opening of our first real athletic field located on the site of the present stadium. At that time it was known as "Alumni Field." Previously all home games were played on the green in the center of the town. We felt that we had a real athletic layout for there was a grandstand which would seat about 1000 spectators with dressing rooms and showers under the stands.

The field was not well drained; conse- quently when we had heavy rains there were miniature lakes all over the playing field. Even with this drawback we were as well if not better equipped than most colleges in our class.

The fall of '93 saw the development of the Flying Wedge and the beginning of the mass plays which required men with plenty of weight, strength and ability to take punish- ment. Blocking, in this type of play, was not of importance for there was little open field running except on kick returns.

'97 had a good quota of football stars from high schools. Ed Hall '92, as athletic instruc- tor at the University of Illinois, did some good missionary work for Dartmouth. He sent us George "Tony" Huff, a guard who had played at University of Illinois; "Wally" Mc- Cornack from Englewood High School, Chi- cago; "Aunty" Lewis from Lake-View High School, Chicago; and Hotchkiss from Peoria, Illinois, High-School. All of these men were high grade players. "Wally" McCornack made himself one of the football immortals of Dartmouth, which, when his size is considered (for he never weighed over 145 lbs. fully clothed), is remarkable. Other players were Marshall from St. Johnsbury Academy; Pills- bury from Armsbury, Mass., High School; Fred Perkins from Dummer Academy; Mor- rill from Cincinnati High School; "Kid" Fol- som from Dover, N. H., High School; Kelly from Bradford, Mass., High School, and eral other men who played in prep schools but who for different reasons never played while in college.

The season of '93 was successful, for both Amherst and Williams, our main rivals, were beaten by large scores. We were not, in those days, considered in the same class with Har- vard, Yale and Princeton.

The fall of '94 saw the flying wedge out- lawed and the game was opened, as at pres- ent, with the kick-off, but the mass plays, guards back and other power plays were be- ing developed. Dr. Wurtenburg of Yale was employed for that season as coach to succeed Moyle who had gone to Brown. Wurtenburg continued as coach for four or five years and was followed by Jennings '99, then by Mc- Cornack '97.

In the fall of '95, because of the objection of Amherst and Williams to our playing Med- ical students, we had our first all-undergradu- ate team. Fear was expressed that we would be weakened by the lack of the experienced men whom we drew from the Medical School, but in spite of this we had our usual success and defeated both Amherst and Williams, but were beaten by Brown. The undergraduate body was enlarged by the class of '99 which was, up to that time, the largest freshman class ever to enter the College, with many seasoned football players from academies and high schools.

We of '97 saw, during our collegiate years, the beginning of the change to a more open game and gradual curtailment of the mass power plays. Each year there was an effort to outlaw the elements which would make the game dangerous. In those days a man who left the game could not return, therefore slight and sometimes serious injuries were ignored when the player was a key man. Also, on this account, the squads were small. This is real- ized when we find how few men received the award of the block D: 12 men in '93, '94 and '96, and 14 men in '95. During this time de- ceptive plays began to be developed. The double pass had been in use for a long time and is still used. The only play which we at Dartmouth can claim as originating was called the "sideline sneak." It was used very effectively in our games in '95. When we had the ball so close to the sidelines that there was only room for the guard between the center and the sideline, a fake was made toward the long side of the line, a delayed pass was made and the back went straight down the sideline. The discovery of this play resulted when one of our backs did not get the signal and stood in his tracks. When he finally got the ball he saw an opening and ran down the sideline for 20 yards. After that the play was frequently used when the opportu- nity offered.

During the '96 season McCornack and Macandrew worked a play which resulted in a touchdown which tied Brown 10 to 10 in a game which was supposed to be an easy vic- tory for Brown. Dartmouth had been using a mass revolving play on the center of the line. Late in the game with the ball in the center of the field with the score 10-4 against us, this mass play was started but when the whole Brown line was drawn in, suddenly McCornack carrying the ball with Macandrew as interference sneaked out of the mass and raced for a touchdown. We other Dartmouth players were as much surprised as the Brown team. It was a play cooked up by McCornack who had passed the ball first to Macandrew; then when the play started, Macandrew passed the ball to Wally and both headed down the field without being noticed by either side until they were in the clear. This play was tried many times afterwards but never was successful for long gains. Perhaps the fact that only the two men knew about it on either side was what made it so successful the first time.

In looking back upon the football material in college during the mid 'go's we can feel some pride in their record because the pres- ent-day coach would not. be able to make even a start with so few men. Yet in evaluating the abilities of these men, I am sure that most of them who made the team in those days would be able to give a good account of them- selves today. We can be sure that no player of today could show more zeal or ability than McCornack. He would have been a triple- threat, for he could run well in the open field and kick accurately, and if the forward pass had been allowed at that time he would have been adept at that. In addition he was a sure and vicious tackier, able always to diagnose the opponents' plays

In conclusion, I want to describe an inci- dent which happened in the final game of the '95 season which will illustrate the rugged- ness of the players at that time. Randall '96 was playing guard. During the early part of the game he was kicked in the mouth. Hav- ing two teeth broken off at the gums and both his upper and lower lips cut all the way through, he calmly spit his teeth into his hand and walked to the sidelines where he handed them to "Squash" Little and told him to hold them for him until the game was over. When asked if he was leaving the game, his reply was, "Hell no. One of those backfield men did it—l don't know which—and I am staying in until I get them all." He finished the game but every one of the backfield men on the opposing team left the game before it was finished. Do not assume from this that Bill Randall was a "dirty" player for he was never guilty of this type of play. I never knew him to be penalized during his playing ca- reer. He was a hard tackier and if he was responsible for any players leaving the game it was because they could not take the punish- ment of hard tackling.

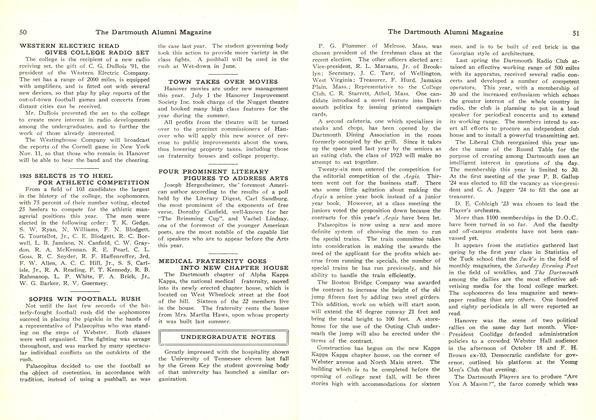

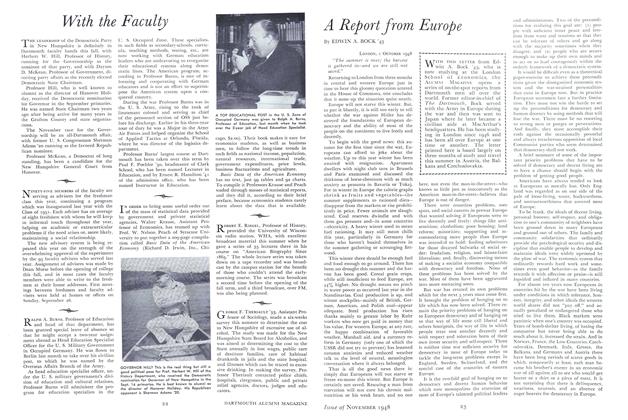

THE BIG GREEN ELEVEN OF 1895: The author, Dr. Walter F. Kelly '97 reclines in the left foreground, balanced at the right by D. C. Macandrew '98. Top row: W. J. Randall '96, A. J. Abbott '98, 8. T. Marshall '97, c. H. Pillsbury '97. Second row: H. D. Lakeman '96, L. Oakes '99, G. H. Abbott '96, F. W. Cavanaugh '99. First row: F. J. Crolius '99, Mgr. J. C. Hadlock '96, Capt. W. E. McCornack '97, J. B. C. Eckstorm '98, G. M. Lewis '97.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCIVIL RIGHTS IN AMERICA

November 1948 By ROBERT K. CARR '29, -

Article

ArticleA Report from Europe

November 1948 By EDWIN A. BOCK '43 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1924

November 1948 By JAMES T. WHITE, RICHARD A. HENRY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1948 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Article

ArticleConvocation Address

November 1948 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

November 1948 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, MORTON C. JAQUITH