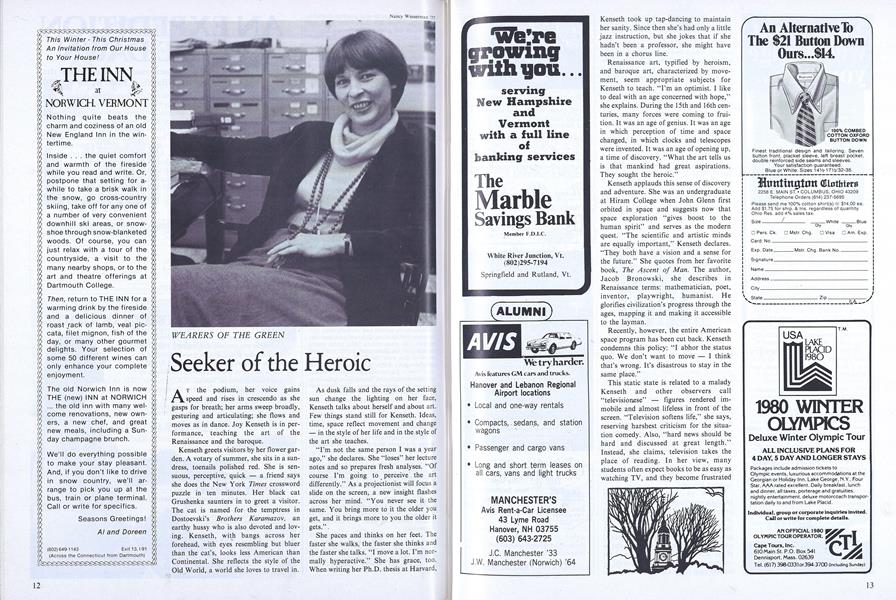

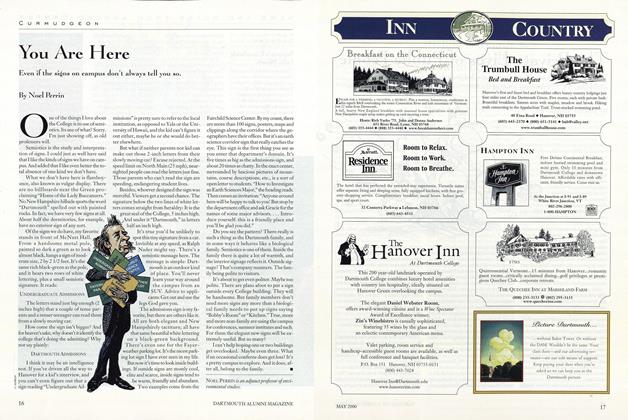

AT the podium, her voice gains speed and rises in crescendo as she gasps for breath; her arms sweep broadly, gesturing and articulating; she flows and moves as in dance. Joy Kenseth is in performance, teaching the art of the Renaissance and the baroque.

Kenseth greets visitors by her flower garden. A votary of summer, she sits in a sundress, toenails polished red. She is sensuous, perceptive, quick — a friend says she does the New York Times crossword puzzle in ten minutes. Her black cat Grushenka saunters in to greet a visitor. The cat is named for the temptress in Dostoevski's Brothers Karamazov, an earthy hussy who is also devoted and loving. Kenseth, with bangs across her forehead, with eyes resembling but bluer than the cat's, looks less American than Continental. She reflects the style of the Old World, a world she loves to travel in.

As dusk falls and the rays of the setting sun change the lighting on her face, Kenseth talks about herself and about art. Few things stand still for Kenseth. Ideas, time, space reflect movement and change — in the style of her life and in the style of the art she teaches.

"I'm not the same person I was a year ago," she declares. She "loses" her lecture notes and so prepares fresh analyses, "Of course I'm going to perceive the art differently." As a projectionist will focus a slide on the screen, a new insight flashes across her mind. "You never see it the same. You bring more to it the older you get, and it brings more to you the older it gets."

She paces and thinks on her feet. The faster she walks, the faster she thinks and the faster she talks. "I move a lot. I'm normally hyperactive." She has grace, too. When writing her Ph.D. thesis at Harvard, Kenseth took up tap-dancing to maintain her sanity. Since then she's had only a little jazz instruction, but she jokes that if she hadn't been a professor, she might have been in a chorus line.

Renaissance art, typified by heroism, and baroque art, characterized by movement, seem appropriate subjects for Kenseth to teach. "I'm an optimist. I like to deal with an age concerned with hope," she explains. During the 15th and 16th centuries, many forces were coming to fruition. It was an age of genius. It was an age in which perception of time and space changed, in which clocks and telescopes were invented. It was an age of opening up, a time of discovery. "What the art tells us is that mankind had great aspirations. They sought the heroic."

Kenseth applauds this sense of discovery and adventure. She was an undergraduate at Hiram College when John Glenn first orbited in space and suggests now that space exploration "gives boost to the human spirit" and serves as the modern quest. "The scientific and artistic minds are equally important," Kenseth declares. "They both have a vision and a sense for the future." She quotes from her favorite book, The Ascent of Man. The author, Jacob Bronowski, she describes in Renaissance terms: mathematician, poet, inventor, playwright, humanist. He glorifies civilization's progress through the ages, mapping it and making it accessible to the layman.

Recently, however, the entire American space program has been cut back. Kenseth condemns this policy: "I abhor the status quo. We don't want to move — I think that's wrong. It's disastrous to stay in the same place."

This static state is related to a malady Kenseth and other observers call "televisionese" — figures rendered immobile and almost lifeless in front of the screen. "Television softens life," she says, reserving harshest criticism for the situation comedy. Also, "hard news should be hard and discussed at great length." Instead, she claims, television takes the place of reading. In her view, many students often expect books to be as easy as watching TV, and they become frustrated when faced with difficult works. "Reading," she says, "should be like breathing."

Television simplifies, too, by portraying issues in "black and white." Kenseth looks for the distinctions. "One of the joys of life is its complexities," she says. She tries to demonstrate these nuances in her classes, teaching students to perceive art and ideas in many different lights. By cultivating tolerance, people will not be afraid of "otherness." To Kenseth, this fear of the unknown causes many of the world's misunderstandings, conflicts, and wars.

Students at Dartmouth are not always young. Two summers ago, Kenseth lectured at Alumni College when the course theme asked, "Men and Women: What's the Difference?" Posed with the question again, she laughs and says, "Of course I'd thought of it, but not in those terms. I had never looked at art that way." She enjoyed teaching the adults, and claims they are "a lot brighter than their children think they are."

Another pleasant Alumni College experience periencewas meeting faculty from other departments. Her own department is relatively small, and Kenseth seldom comes in contact with professors outside her discipline. She also is among the growing group of young single professors at Dartmouth, and she worries that the College has done little to meet the needs this change brings forth. No longer is the faculty composed almost totally of married men with families, yet Dartmouth stands out as the only Ivy League school without a faculty club. "There is no major effort to bring the faculty together to exchange ideas," she says. "The faculty needs its common ground."

Kenseth, who came to Dartmouth in 1976, also discusses the wide numerical disparity between men and women with tenure at the College. Out of a tenured faculty of 158, only six women hold tenured positions. She argues for change to admit more women to the faculty and to make these women more welcome in the community. She argues as a humanist — her approach to life and to art. As she coneluded in an Alumni College lecture, "In the end men and women are very much the same. They have to deal with life and death. And great art in the end deals with life and death."

Kenseth studies history through art because she trusts it more than political speeches. "To me a work of art is a fact of history," she says. "It's an idea that came about in a certain time and place." In art, history is immutable; it cannot be rewritten. It can only be studied in greater depth.

"Teaching art demands being in front of the object," says Kenseth. This spring she will take a group of students to Italy on Dartmouth's first art history foreign study program. They will view the art and architecture of Florence and nearby centers. But Rome is her real love. In 1968, she traveled abroad on a Fulbright scholarship for the first time. She returns at every opportunity and currently is on leave in Italy finishing research on her book Sculptors of the Marvelous in 17th-century Rome.

Art and travel are linked: While in Brazil some years ago, she sold her own paintings to make money for a trip to Antarctica to view the wildlife. ("It's so pristine there — you feel as though that's the beginning and end of things.") But Kenseth as art specialist has few accolades for her own work. "I have been in a virtual decline since the age of 12," she jokes. "I'm a better teacher than a painter."

On return trips to Hanover from abroad, she lugs home crates of pasta. She loves to cook hot and spicy food. Her classes are invited to her home and treated to Italian cuisine.

She feeds the students' stomachs, but she also sees to their souls. "Deep down, students' emotional lives have to be fed," says Kenseth, alluding to the way art is an expression of emotion. She admits that there are those who slight art history as a discipline of relatively little importance, but argues that "once a student as a human being closes all doors to the art, he's betraying his spirit."

Kenseth opens doors to new worlds. "What the artist is dealing with is the world around feeling. The way it is done comes straight from the artist's heart. That's its special truth."

This is a special truth to be shared with students. Kenseth brings to the class the emotion which the artist brings to the pallet and the sculptor brings to the marble. And she hopes that when students leave her classes, "for the rest of their lives they can see a work of art and find a friend."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureUncle Sam and Mother Dartmouth

November 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureIt's Where We're Coming From, Citizens

November 1979 By Jeffrey Hart -

Feature

Feature'A need for someone who holds my views'

November 1979 By William M. Hill -

Article

ArticleGadfly

November 1979 By M.B.R -

Article

ArticleA Little More Anarchy, Please

November 1979 By Bruce Ducker '60 -

Article

ArticleRags to Riches

November 1979 By Beth Baron '80