MAURICE MANDELBAUM '29 at my request wrote the following brief review of a book about a Dartmouth man, "George Sylvester Morris of the Class of 1861, written by Marc E. Jones, and published by David McKay in 1948. Mr. Mandelbaum says:

"This biography is a full-length study of the life and thought of a distinguished Dartmouth graduate, Morris, a native of Norwich, Vermont, who graduated in '61 and subsequently also earned his M.A. while serving as a tutor at the College.

"Jones' study of Morris' formative years throws light on the curriculum and intellectual interests of the College in the mid 19th century, but the main emphasis of the work is, of course, on Morris' philosophic views. These views were a significant expression of the idealist movement in American philosophy, and it is through his exemplification of that movement that Morris is now chiefly recalled. It is also noteworthy that Morris was John Dewey's teacher at the newly founded Johns Hopkins University, and later brought Dewey to the philosophy department of the University of Michigan, of which Morris was chairman. When Morris died, at the age of 48, Dewey succeeded him. Of him Dewey has recently written: 'I have never known a more single-hearted and whole-souled man.' "

I reviewed in these pages Robin Maugham's book Nomad which concerned the Arabs in the Middle East. The latest book of his to come into my hands is his NorthAfrican Notebook (London, Chapman & Hall, 1948) which gives a fairly entertaining account of a six-months journey through Spain, Morocco, Algeria, Tunis and Libya, ending in Egypt last spring. On the whole the picture he gives is a little too superficial but he does present a sympathetic view of the Arabs in North Africa and explains their connection with the Arabs in Arabia. He finds that the French and Spaniards are, .on the whole, the exploiters as of old, and that the Arabs regard the U.N.O. as a facade behind which the big powers wrangle at the old game of power politics. In spite of two devastating world wars it is "the Old Army Game" all over again. He finds that "no European power has yet succeeded in creating moral solidarity between natives and its own nationals when both are in considerable numbers." Maugham thinks that the United States and Great Britain should proclaim a Monroe Doctrine for the Middle East, and then they should try to persuade France and Spain to adapt themselves to a new relationship with Arab countries based on mutual dependence. Any relationship, he thinks, based on fear and inequality will produce evil results. He believes that the damage done is reparable, once the evil inherent in the relationship between the Arabs and France and Spain is removed. The Europeans must display more compassion (and less greed), and the Arabs more commonsense.

Through Dr. Robert M. Stecher '19 I have been introduced to an excellent series of books published by Henry Schuman, Inc., N. Y., called "The Life of Science Library." One that would interest anyone who likes ships is Charles E. Bibson's The Story of the Ship, 1948. The book is well printed and bound and contains 27 illustrations. The author begins with the earliest known ships (about 4000 B.C.) and carries the reader down to the magnificent "floating palace" the Queen Mary. There is a glossary of sea terms and a list of recommended reading.

The keynote volume in the series is TheLife of Science written by George Sarton, Professor of the History of Science at Harvard, and published in September 1948. Max H. Fisch, whom I remember meeting at the Cleveland Medical Library during the war, writes the introduction and points out that the books in "The Life of Science Library" speak the language not of scholars but of lay men and women, girls and boys. This book is directed, then, to the intelligent reader interested in science, that octupus of our day, which has everybody scared, many bewildered, and many with Robert Frost, defiant. There are essays on Leonardo, Renan, Herbert Spencer, the history of medicine versus the history of art, the spread of understanding, and so on. This is for those who want a history of science that is not too complicated and that all can understand.

Paul H. Oehser and Dorothy Stimson write in Sons of Science and Scientists andAmateurs the histories, respectively, of the Smithsonian Institution and the Royal Society in London. Both books are illustrated, competently written, and amazingly interesting to those of us who seldom realize the immense love, labor, and thought which has gone into the founding and development of such great institutions.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE ARCTIC

April 1949 By TREVOR LLOYD, -

Article

ArticleConcerning Admissions

April 1949 By H. CLIFFORD BEAN '16 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetter from Oxford

April 1949 By CHARLES G. BOLTE '41 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1949 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleDeaths

April 1949 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

April 1949 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING

HERBERT F. WEST '22

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

February 1936 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

January 1938 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

May 1944 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

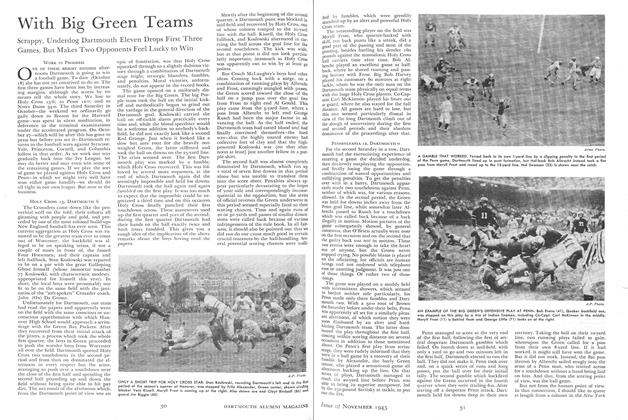

ArticleHanover Browsing

November 1945 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksNO PLACE TO HIDE

January 1949 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

February 1952 By HERBERT F. WEST '22

Article

-

Article

ArticleMasthead

DECEMBER 1998 -

Article

ArticleThe Musical Clubs Trip

May 1929 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleWith the D. O. C.

December 1938 By J. W. Brown '37. -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

March 1933 By J.S.M. '33 -

Article

ArticlePROFESSOR KELLEY ASSISTS IN KOSCIUSZKO MEMORIAL

March, 1926 By Mr. Rostworowski -

Article

ArticleTribal Law

MARCH 1999 By SHIRLEY LIN '02