President Bush's missile defense plan won't shoot down our fears. It will only create new ones

Most americans agree that the attacks of September 11 changed everything. But another, less dramatic event recently took place that may also greatly change the security not just of the United States but of the entire world: On December 13, 2001, President George W. Bush announced that the United States is withdrawing from the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty. He claimed that the treaty, ratified by the United States and the Soviet Union in 1972, hinders our government's ability to develop new ways to protect the American people from nuclear attacks by terrorists or rogue states.

Ironically, the sweeping effects of September 11 did little to alter views of missile defense. Those who previously favored missile defense systems (such as former President Ronald Reagan's "star wars" plans) now more than ever believe them to be necessary. Those previously opposed now seem even more fervent, arguing that we do not need a $150 billion defense network to protect ourselves against terrorists armed with box cutters and butter knives.

President Bush favors a comprehensive missile defense system deployed on land and sea and in space. The technical challenges involved are so enormous that many people doubt the system could ever work. Yet advocates see the plan as the nations best bet against four chilling nuclear scenarios: a deliberate, massive attack from Russia, China or other countries with large nuclear arsenals; a small-scale attack from a so-called rogue nation; a nuclear strike from terrorists; and accidental launches of nuclear warheads.

But Bush's plan would eliminate none of these scenarios. In fact, his national missile defense system would create more problems than it solves.

We already possess an effective defense against deliberate, massive missile attack: the doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD). The premise of MAD is that if adversaries possess secure second-strike capabilities, neither will launch a first assault. This doctrine guided our nuclear strategy during the four decades of the Cold War and still works.

The destabilizing effects of missile defense, on the other hand, are likely to yield dangerous unintended consequences. Anything that decreases Russian and Chinese confidence in their second-strike abilities might lead them to adopt dangerous hair-trigger, launch-onwarning strategies. China worries more than Russia about an American missile defense system, despite having a deterrent force large enough to ensure that a preemptive American attack would be unable to wipe out all its missiles. If the United States deploys part of its defensive system near the Chinese border to destroy missiles before or just after launch (the easiest time to destroy a nuclear missile is right after launch, when it is burning hotly and moving relatively slowly), China would probably expand and fife upgrade its forces. This in turn is likely to precipitate a surge in the nuclear arms race of its South Asian neighbors. These developments would increase the global risk of accidental nuclear strikes.

It is equally a mistake to think that a missile defense system is necessary to deter Iran, Iraq and North Korea -Bush's so-called 'Axis of Evil"—from using their limited nuclear arsenals against us. This logic only makes sense if we believe that leaders such as Iraq's Saddam

Hussein are so irrational that they either don't expect or don't care about U.S. nuclear retaliation—which would be immediate and massive.

With the nation so focused on the war against terrorism, fears of nuclear terrorism are understandable. However, a ballistic missile is not the most likely vehicle a terrorist would use to deliver a nuclear weapon. Ballistic missiles are expensive, dangerous to build and handle, and difficult to hide. Cheaper, safer and easier alternatives are readily available to would-be nuclear terrorists. As long as terrorists are willing to die in the attack, it is far simpler for them to use a truck, plane or boat to deliver a nuclear strike. Suicide bombers who are determined to give their lives to their cause are not deterrable. The challenge is to stop them before they begin their journey to their target, whatever their means. A missile defense system is useless against the kinds of terrorist attacks that have happened recently and those that are most likely to occur in the foreseeable future, including nuclear terrorism.

Then there is the fear of nuclear accidents. In January 1995 Russia came within the turn of a key of firing what they believed would be a retaliatory nuclear strike at the United States. This neardisaster resulted from a Russian bureaucratic snafu that led them to mistake a Norwegian weather rocket for an American intercontinental ballistic missile. If this could happen during a time of relative peace, we can imagine the increased risks during times of tension.

How does this problem relate to the debate about missile defense? When countries adopt launch-on-warning strategies, no matter what the size of their nuclear arsenals, the risk of large-scale accidental launches increases dramatically. Confidence-building measures, such as observable no-first-use policies and mutual arms inspections—the kind of cooperation over nuclear weapons maintenance and storage that is taking place between Russia and the United States—are much better strategies than missile defense for preventing nuclear nightmares. Renewal of the ABM Treaty would be an important step toward that trust.

Paradoxically, by trying to protect ourselves with a missile defense system, we would place ourselves in more danger. Our adversaries will not sit still in the face of advancing American defenses. For every action we take, they will have some strategic reaction. When we consider the counterbalancing effects a missile defense system will likely generate, even good defenses are a bad idea.

Allan C. Stam is an associate professor ofgovernment and deputy director of the Rockefeller Center.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

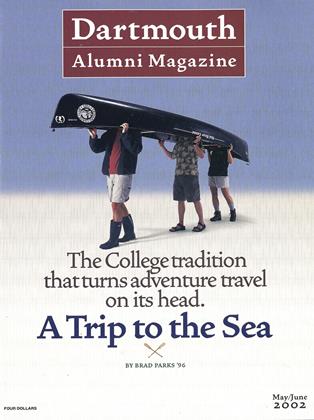

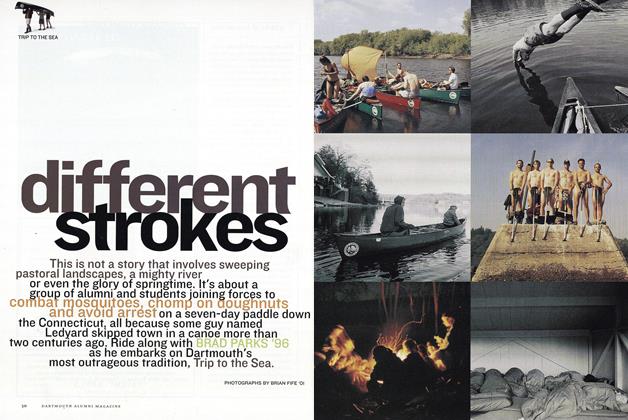

Cover Story

Cover StoryDifferent Strokes

May | June 2002 By Brad Parks ’96 -

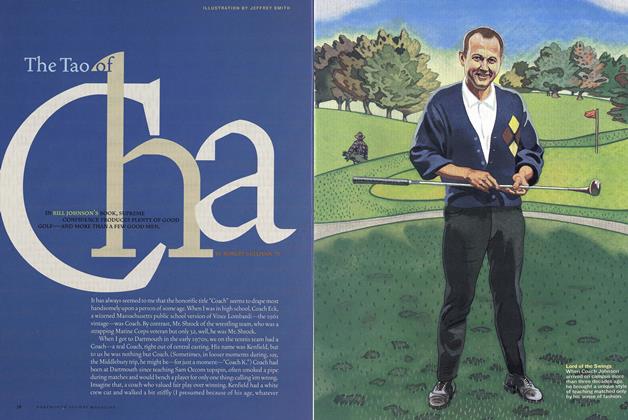

Sports

SportsThe Tao of Cha

May | June 2002 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryOut of Bounds

May | June 2002 By Sarah Lang Sponheim ’79 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

May | June 2002 -

Article

ArticleThe Gift of Education

May | June 2002 By President James Wright -

Class Notes

Class Notes1994

May | June 2002 By Nihad M. Farooq

Article

-

Article

ArticleD.C.A. ALUMNI COMMITTEE RETRACTS NEAR EAST SUPPORT

March, 1922 -

Article

ArticleExam Sets Record

October 1943 -

Article

ArticleHonoring a Rat

SEPTEMBER 1981 -

Article

ArticlePhysician honored by professorship

September 1986 -

Article

ArticleWinter Schedules

December 1954 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

December 1954 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '29