FIFTY-FIVE years ago, this present June, a young fellow, still in his teens, stood looking out of the upper hall window of Hanover's old Frary Hotel. The father of the boy had brought him on to Commencement, peradventure he might get into the college spirit. Up to that moment he still lacked the spirit.

It was midnight, and incredible as it may seem, Hanover was asleep, or at least dead to the world. There was really nothing for which to keep awake after the last gun of Commencement had been fired. Also the Hanoverians were weary with well doing. The moon was the only illumination, for electric lights were unknown. The youth could not call up his entertainers, the Crosbys, the Longs, the Howes, as there were no telephones. There could be no cooling off in a motor car, as they were unheard of. The moon made visible a haze in the air, evidence of the recent passing of Allen's and Swazey's coaches, the farm wagons and carryalls, with an occasional dog-cart or four-in-hand; for the roads down the hill or to the Lebs were deep with dust.

There was not a sound in the' hotel. Hod Frary, weary with wielding his gory carving knife in that hectic week, was doubtless dreaming of the Squire's unpaid bill. Mrs. Frary was exhausted from serving meals surcharged with curry, and skating with sore feet across the dining room floor. Oscar Johnson, the clerk, was unconscious in his little bedroom next the alley, clutching a string attached to a bolt, which he pulled in his sleep for those who dared to be out after hours. Oscar was tired of living and answering "foolish questions."

The boy looking out of the window found little to excite him in the view. The hospitable Balch house loomed large diagonally opposite. The church and vestry, Hanover's religious landmarks for so many years, were dimly visible. Those of lighter mind called them the "Cow and the Calf." Far up faculty avenue, ending with Rope Ferry, stood the giant elms, splendid guardians of Dartmouth dignity.

For the youth standing there it had been a rather dreary and meaningless day. To be sure there was novelty in seeing every description of vehicle driven into town from early morning. The campus, with the scores of teams tied to the fence, had the appearance of a country horse sale or a circus encampment. He had watched the eager families pouring into the church to see and hear son and brother graduate amid a flood of oratory, interspersed with Latin phrases which few understood besides the professor whose job it was to compose them. The boy had sat for hours in an uncomfortable pew listening to the seniors explaining the earth and the fulness thereof. As these forensic fireworks continued during the greater part of the day, with no intermission for luncheon, it required considerable finesse on the part of hungry relatives to reach into boxes of food and masticate it in an unobtrusive and academic manner. The concert which had closed the exercises had been a rather weird mixture of instumental selections, vocal solos and allegedly humorous recitations. At that time there was a tradition that if you watched closely enough, you might discover the Hanover cracker when the soprano (always from Boston) reached for high C. Be that as it may, she was a gorgeous creation with tremendous sleeves.

The tumult and the shouting died, and with it disappeared good Judge Nesmith and other trustees, together with the prominent and common people. As they mostly were encased in linen dusters, it was difficult to differentiate between the aristocracy and the great unwashed. Perspiration and dust left little to be desired in the outline maps of Africa or other continents sketched on the backs of these garments.

"So this is a Dartmouth Commencement" said the boy to himself. Up to that moment he had not been conscious of a thrill. If this was the grand climax to four years of college training, what was there in it for him? He was about to leave the window and seek the doubtful restfulness of a Frary bed, when arrested by distant singing. From far up faculty avenue came the alluring music of a male quartet:—

"How dear to my heart are the scenes of my childhood When fond recollection presents them to view," ending with— "The old oaken bucket, the iron bound bucket The moss covered bucket that hung in the well."

The four voices were in perfect harmony, but the tenor stood out in a peculiarly beautiful timbre, perhaps uncultivated, but with a quality extremely rare. The listening youth had been accustomed to the best concert hall performances, but this was different! He did not know till years afterwards that this was the swan song of the college glee club singing its goodbye to the College and to one another: the camaraderie of song. They were "singing to one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs." Their hearts were too full for talk, but they could and must sing.

The boy stood entranced, listening for more.

The singers approached, passing the homes of a group of professors. Again came the welcome music: never mind if the words were in an unknown tongue:— "Vivat academia Vivant professores Vivat academia Vivant professores Vivat membrum quadlibet Vivant membra quaelibet Semper sint in flore Semper sint in flore."

There was no sign from the professorial houses. Several of the learned men had boasted that they did not know one tune from another. To them there was no relationship between song and science. To the listener in the window there was, at that moment, no science but song.

The quartet was now passing the vestry and church. Once more came the delightful combination of blended voices:—

"I'm but a stranger here, Heaven is my home; Earth is a desert dreer, Heaven is my home. Danger and sorrow stand round me on every hand, Heaven is my Fatherland, Heaven is my home."

Again that tenor voice seemed to mount up to heaven in the repeated refrain— "Heaven is my Fatherland, Heaven is my home." '

The boy in the window felt the fellowship and deep sentiment in the singing, as this Dartmouth quartet expressed the beauty of the night, but deeper still, the thought that it was probably the last time the four would ever sing together.

Passing the campus there were several light songs of the time, "The bull dog on the bank," "Upidee," and "Landlord fill the flowing bowl."

Then the youth became aware that the singers had reached the hotel, and had seated themselves, just beneath him, on the old stone steps. To a humming accompaniment, the tenor sang—

"Stars of the summer night, Far in yon azure deeps, Hide, hide your golden light She sleeps, my lady sleeps." This was followed by "Way down upon the Swanee ribber," ending with that most tender and pathetic refrain in the history of American song—

"Oh, darkies how my heart grows weary Far from the old folks at home."

The four young men undoubtedly thought that they were singing to deaf ears, and might not have been moved at the knowledge that only a homesick boy was listening. Yet they might have been interested could they have realized the hero worship born in the heart of this youth, and that they were responsible for an emotion such as comes to a soul but once or twice in a lifetime. Much as he longed to speak to them, or even to touch them, the boy felt that they were too far above him. He stood fairly trembling in the presence of true greatness. The quartet arose, and without a word, strolled across the campus, passing the old well which furnished water for the Dartmouth-Thornton-Reed- Wentworth students, on the pump and carry system.

Their departure seemed like an unbearable calamity to the youth. He watched them pass between the big posts, once actually broken in the bodily impact of a "rush." They walked up in front of the four old buildings. The boy's longing for another song amounted to a prayer.

Just why they sang this particular selection is not known. The beautiful setting of a fateful love song may have appealed to the singers, as appropriate to this farewell. The college man is not often given credit for the deep sentiment he feels, but cannot reveal. Like a benediction the words and music floated out from the ancient college buildings, representing multitudes of Dartmouth men who had here said farewell, and gone hence.

"Forsaken, forsaken, forsaken am I Like a stone in the causeway, my buried hopes lie; I go to the church yard, my eyes fill with tears; And kneeling, I weep there O my love loved for years; And kneeling I weep there O my love loved for years."

Before the three verses were finished every window in the three halls was lighted. Perfect silence followed the fading melody. And then, wonderful to relate, the response of cat calls,.horns and gibes which usually greeted late serenaders failed to come, but in their place was a genuine burst of applause. Then all lights went out.

The youth in the window was doubtless the only individual in Hanover who heard all of those swan songs. Not until fifty-five years after did he know who the singers were, and particularly the tenor whose voice so moved him. These two never met, but the boy who heard the singing which decided him for college, afterward ministered to the sick and dying father of the fellow with the compelling voice, although ignorant at the time that he was making a kind of contact with his benefactor. If there is any point in this bit of Dartmouth history, it may be found in a delayed appreciation for a most beautiful and artistic closing of that Commencement of long ago, an appreciation from any who did or did not have the privilege of hearing it. But a more impressive fact is in the knowledge that when the voice fails, the song goes on. Few Dartmouth men ever were called upon to go through such strange disappointments, sorrows and tragedies as the member of that glee club with the tenor voice. There were times in his life when he could have repeated the refrain of the last song as applying to himself—

"Forsaken, forsaken, forsaken am I."

Every fond dream and ambition of his college course was frustrated, and to cap the climax of seeming disaster came blindness which continued the last twenty-one years of his life. In darkness he groped his way to the little garden and hen house, feeling his direction by guiding strings. His cup was full.

But here is the miracle: he discovered that calamity may be the path of victory and deep content. If the dreams and ambitions of his youth had come true, he would never have been the man he became. Young and old in the little town where he lived came under the benign and cheering influence of a strong life. In the largest sense he could have said daily—

"I sang a song into the air, It fell to earth, I know not where, For who has sight so keen and strong That he can follow the flight of a song? Long, long afterward from beginning to end I found the song in the heart of a friend."

When the end of life approached, the Dartmouth singer of long ago said to a friend, "My philosophy of life is summed up in—

"Sunset and evening star And one clear call for me! And may there be no moaning of the bar When I put out to sea."

Who was the boy who listened to the "Midnight Song" so many years ago? And who wasthe tenor whose sweet voice sounded across thecampus on the eve of the departure of the "grandold seniors" for the "wide, wide world"?Little do these questions matter. Dr. Bartletthas caught a moment precious in the lives ofgenerations of Dartmouth men. He has set itdown at a time when another group of seniorsprepares to go out from their Alma Mater, andas his own class looks forward to its fiftieth reunion..

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

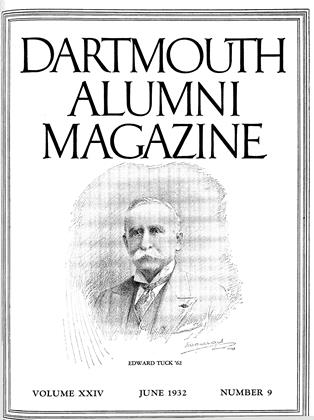

ArticleEdward Tuck: A Biographical Sketch

June 1932 By Horatio S. Krans -

Article

ArticleDartmouth's Greatest Benefactor

June 1932 By Russell R. Larmon -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

June 1932 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1926

June 1932 By J. Branton Wallace -

Sports

SportsIron Man

June 1932 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

June 1932 By Arthur E. McClary

Article

-

Article

ArticleDRAMATIC CLUB

February, 1910 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Articles

MAY 1959 -

Article

ArticleFRESHMAN WEEK PROGRAM AND TABLE OF EVENTS • CLASS

October 1975 -

Article

ArticleArtists 22, Philistines 14

OCTOBER 1999 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleChange & Growth

May 1940 By The Editor -

Article

ArticlePublication Schedule

May 1942 By The Editor