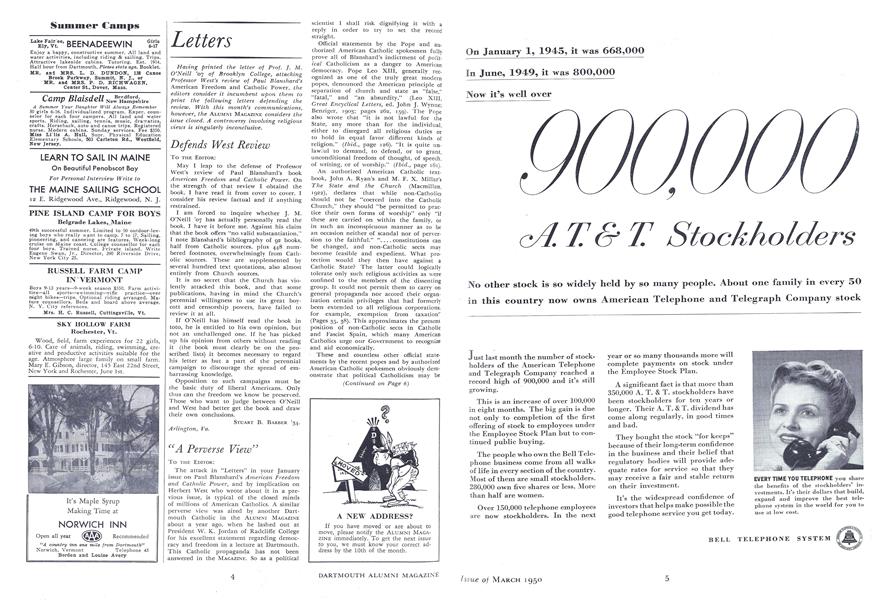

Having printed the letter of Prof. J. M.O'Neill '07 of Brooklyn College, attackingProfessor West's review of Paul Blanshard's American "Freedom and Catholic Power, theeditors consider it incumbent upon them toprint the following letters defending thereview. With this month's communications,however, the ALUMNI MAGAZINE considers theissue closed. A controversy involving religiousviews is singularly inconclusive.

Defends West Review

To THE EDITOR:

May I leap to the defense of Professor West's review of Paul Blanshard's book American Freedom and Catholic Poxver. On the strength of that review I obtaind the book. I have read it from cover to cover. I consider his review factual and if anything restrained.

I am forced to inquire whether J. M. O'Neill '07 has actually personally read the book. I have it before me. Against his claim that the book offers "no valid substantiation," I note Blanshard's bibliography of 92 books, half from Catholic sources, plus 448 numbered footnotes, overwhelmingly from Catholic sources. These are supplemented by several hundred text quotations, also almost entirely from Church sources.

It is no secret that the Church has violently attacked this book, and that some publications, having in mind the Church's perennial willingness to use its great boycott and censorship powers, have failed to review it at all.

If O'Neill has himself read the book in toto, he is entitled to his own opinion, but not an unchallenged one. If he has picked up his opinion from others without reading it (the book must clearly be on the proscribed lists) it becomes necessary to regard his letter as but a part of the perennial campaign to discourage the spread of embarrassing knowledge. Opposition to such campaigns must be the basic duty of liberal Americans. Only thus can the freedom we know be preserved. Those who want to judge between O'Neill and West had better get the book and draw their own conclusions.

Arlington, Va.

"A Perverse View"

To THE EDITOR:

The attack in "Letters" in your January issue on Paul Blanshard's American Freedomand Catholic Power, and by implication on Herbert West who wrote about it in a previous issue, is typical of the closed minds of millions of American Catholics. A similar perverse view was aired by another Dartmouth Catholic in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE about a year ago, when he lashed out at President W. K. Jordan of Radcliffe College for his excellent statement regarding democracy and freedom in a lecture at Dartmouth. This Catholic propaganda has not been answered in the MAGAZINE. SO as a political scientist I shall risk dignifying it with a reply in order to try to set the record straight.

Official statements by the Pope and authorized American Catholic spokesmen fully prove all of Blanshard's indictment of political Catholicism as a danger to American democracy. Pope Leo XIII, generally recognized as one of the truly great modern popes, denounced the American principle of separation of church and state as "false," "fatal," and "an absurdity." (Leo XIII, Great Encyclical Letters, ed. John J. Wynne; Benziger, 1903; pages 262, 159). The Pope also wrote that "it is not lawful for the State, any more than for the individual, either to disregard all religious duties or to hold in equal favor different kinds of religion." (Ibid., page 126). "It is quite unlawful to demand, to defend, or to grant, unconditional freedom of thought, of speech, of writing, or of worship." (Ibid.., page 161).

An authorized American Catholic textbook, John A. Ryan's and M. F. X. Millar's The State and the Church (Macmillan, 1922), declares that while non-Catholics should not be "coerced into the Catholic Church," they should "be permitted to practice their own forms of worship" only "if these are carried on within the family, or in such an inconspicuous manner as to be an occasion neither of scandal nor of perversion to the faithful." . constitutions can be changed, and non-Catholic sects may become feasible and expedient. What protection would they then have against a Catholic State? The latter could logically tolerate only such religious activities as were confined to the members of the dissenting group. It could not permit them to carry on general propaganda nor accord their organization certain privileges that had formerly been extended to all religious corporations, for example, exemption from taxation" (Pages 35, 38). This approximates the present position of non-Catholic sects in Catholic and Fascist Spain, which many American Catholics urge our Government to recognize and aid economically.

These and countless other official statements by the recent popes and by authorized American Catholic spokesmen obviously demonstrate that political Catholicism may be as dangerous in theory as Communism to American freedom and democracy. Moreover, because there are possibly 25,000,000 or more Catholics and probably considerably fewer than 100,000 Communists in America, the practical threat of Catholicism appears considerably greater.

Granted that many American Catholics certainly are fine Americans and believe in religious and other freedoms. But when the Church finds the time ripe to assert its oftstated supremacy, American Catholics may have to make a most difficult choice between political (but not theological) Catholicism and American democracy. Yet many Catholic authorities claim that Catholic dogma, both theological and political, is indivisible and must be accepted in toto. Thus a most serious problem faces us all, and Mr. Blanshard's analysis of it is extremely valuable.

Indianapolis, Ind.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The writer is a member of the Department of History and Political Science in Butler University, Indianapolis.

Liberal Arts Research

To THE EDITOR:

Since the alumni drive for additional millions is much more than a matter of academic interest, I would like to offer some comments, although my personal contributions consist largely of an occasional $10.

In my father's time, life was simpler, and by living within his income, the return from his savings equalled his salary in later life. This is not an unusual story, as those few classmates surviving him could testify—perhaps it is typical in some respects. My father never benefited from a pension, or scholarship, or union membership, or relief grant or tax-exempt provisos, or G.I. Bill of Rights. He never enjoyed an expense account, so that if he ate in a restaurant, or attended a convention, or travelled, he had to pay the bill himself. Likewise, whims, personal extravagances, and mistakes were charged to his own pocket.

I mention this in contrast to the present trend towards the security of a corporation or government position. The independence of my father's thinking has likewise disappeared under the impact of involuntary pay roll deductions, welfare taxes, and drive after drive of various so-called charity organizations.

This may seem like a review of Sociology I, but my intention is not to supplemeni President Dickey's excellent report, but to suggest to the Dartmouth Development Council that they seriously consider the possibilities of research projects, or the training of young executives in the Tuck School.

It is obvious that football prestige is not enough when raising money in quantities. Harvard, with a losing team, has already raised better than half of a $20,000,000 goal M.I.T., with no football team at all, has raised $8,800,000 since last June 30.

Recently, Harvard Business School received an endowment with no strings. Income is to be paid to promising young businessmen on the basis of ability alone without proof of financial need or athletic skill. This is a further step in the underwriting of the school by a representative list of big corporations.

M.I.T. has received a number of corporation grants recently, each one making possible another new building; the latest million from the Campbell Soup Co.

The new physics laboratory could be an immediate reality if the resources of the department and faculty and student aptitudes were organized to meet the requirements of the Office of Scientific Research and Development. Dr. Gordon Ferrie Hull, who was considered a "war-monger" fifteen years ago, has lived to see nuclear physics come into No. 1 priority.

In the realm of living things, such as forestry research, Dartmouth would be a natural leader. The cultivation of trees on a scientific basis has already been established as profitable and practical, and lumber companies as well as conservationists are ready for it. Why not a forestry major, which could include skiing and other D.O.C. activities, as well as the study of biology? Reforestation is related to water resources, and multi-dollars will be spent in flood control and power development. '

I am not advocating a Dartmouth University, but I believe that the graduate schools, and graduate students, could direct a certain amount of research to the mutual advantage of the College and society. Research now as never before is being sponsored by government and industry alike. U.S.A.F. now is placing research and development activities on the same staff level as the existing four major staff sections—Comptroller, Personnel, Operations, and Materiel. This also constitutes a new command that parallels other major commands. (See A-N-AF Register, Jan. 28, 1950.)

Research on theoretical levels is certainly a seeking after new ideas, and such seeking of new ideas* should not be incompatible with a liberal arts education. I remember that a Dartmouth graduate, now head of research for du Pont, wrote an article for this very magazine in which he pointed out the importance of research in a liberal arts education.

East Dedham, Mass.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

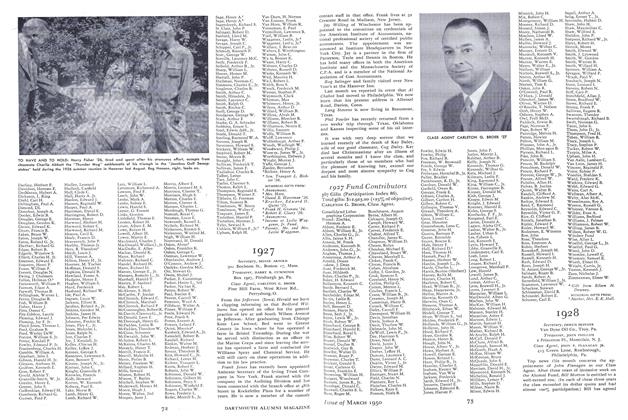

Class Notes1928

March 1950 By OSMUN SKINNER, JOHN PHILLIPS, JOHN E. FLANAGAN JR. -

Class Notes

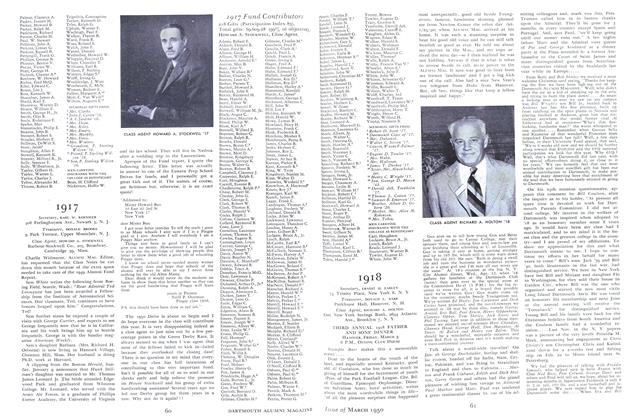

Class Notes1918

March 1950 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

March 1950 By HENRY R. BANK ART JR., FREDERICK T. HALEY, ROBERT W. NARAMORE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1938

March 1950 By JOHN H. EMERSON, WILLIAM H. MCMURTRIE, ROBERT H. CARSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

March 1950 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

March 1950 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN, ADDISON L. WINSHIP II