GENTLEMEN OF THE COLLEGE: This ceremony of convocation opens the 183rd year of Dartmouth's service to human society as an American institution of higher learning. We mark this moment of gathering together in order that we may sense a little more sharply both the joy and the purpose of our common task which, to put it most simply, is to help you to be a better educated man to the end that you may be a better man.

A year ago we gathered here in the face of darkening realities and unnerving uncertainties. We looked forward to a hard year, and the year was not without its difficulties, but is there a man among us who is not a better educated man and, indeed, a better man for having borne himself well through the trouble of these days? I want you to take the bows with the burdens: this college community as a whole faced front during the past year with a maturity worthy of men who understood the full measure of their privilege and of their responsibility in being permitted to pursue liberal studies while the Republic to which we all owe allegiance calls other young men to the duties and, perchance, the death of a soldier.

And now you men in the upper classes who have had one or more years of learning to bear yourselves as men worthy of Dartmouth are joined today by the largest entering class ever to come up the hill onto Hanover Plain. To each of these freshmen, some 750 strong, it is good to say face to face, "You are more than welcome, you are now one of us."

Last year on this occasion I discussed the outlook in world affairs in an effort to help you feel a little more at home in the larger scheme of things which seemed to have terrifyingly little place in it for the plans and purposes of individual fellows such as yourselves. I shall not cover that ground again today, but it might be helpful to say this much about it. I see no reason to think that there has been any radical change in either the outlook or the essential factors. I do believe that the profit and loss sheet of the past twelve months shows a net advantage for the free nations. It is now an imperishable fact that the original aggression in Korea and the compounded aggression of Red China have been contained and hurled back by collective action under the aegis of the United Nations and the leadership of the United States. Whatever else may be ahead beyond the curve of time, this, we may be sure, is one of the really great "firsts" in human history.

Paradoxically, it seems to me that we may today be both closer to World War III and in a better position to avoid it. Closer, because the Politburo of the Soviet Union now knows that the day of cheap aggressions is probably past. If the Soviet Union means to have its way by the use of force, it may soon decide it cannot afford to wait longer. And yet the chances of avoiding that awful possibility seem to me, on any rational basis, to be somewhat better than they were a year ago largely because of what is being accomplished under the leadership of General Eisenhower to bring the strength of united action to that area of the world where aggression could be decisive for the fortunes of the West. Gentlemen, you face a world where the hard-boiled odds of policy may well be on war, but where peace is still a good bet. Whatever these odds may be, I say to you this morning that your best bet is on yourself.

IT is about the bet on yourself that I want to talk with you a little. I have called it your best bet for two reasons: first, because it is the only bet you can make where the outcome is entirely, or largely at least, in your own hands; secondly, because the issue of what a man will be is the only supremely important issue which any man faces in his lifetime. Those taken together, I submit, are two pretty good reasons for glancing up from the state of the nation every now and then for a calm look at the state of yourself and the course of your growth.

During the past few years I have used this occasion to point out certain timetested qualities which it has seemed to me every liberally educated man should covet and cultivate for himself. I have spoken previously of humility, of loyalty, of cooperation and of the integrity in a man out of which alone these other things are fashioned. Today I want to try to carry this effort forward onto higher ground and to say a few words about the moral and spiritual factors in the growth of a man.

Let me avow at once that I enter this discussion as a layman speaking to laymen and in the spirit of one who asks of you only the company of seeking minds and open hearts.

Did you ever stop to think whence comes the content of meaning for those simple but highly prized words "a good man"? I mean, of course, a man who is "good" in the eyes of his fellow men regardless of his station in life, of his knowledge, of his calling or of all else except the way he regards himself in his relations with other human creatures. I suggest to you that in the exact degree that you are unsure of a man in that latter respect you are unsure of his goodness, or even, indeed, to use the term which Robert Frost prefers, you are unsure of his measure as a civilized man. And, gentlemen, this is not just a matter of ideals and church-door ethics. To be very practical about it—whether in business, in government, in war or in the home—when the really big ones have to be faced, you find yourself not just unsure about such a man's "goodness"; you are, regardless of all else, just plain not sure about that man —period.

The moral spectrum of any society ranges from questions of form and manners in seemingly small matters to those issues involving the terms on which human life itself may or may not rightfully be taken by one man from another.

It is a part of every man's liberal education to learn that various answers have been given by different societies and different civilizations to the same moral problems. And you will find that factors of time and circumstances have influenced moral values and standards of conduct even within the same society. But I do urge you to be careful not to misread the meaning of change in matters of morals. Too many bright fellows have missed this turn badly and sadly. The old French adage, the more it changes the more it stays the-same, is true beyond any doubting in the deep moral values of a society. Rules and forms of conduct involving moral consequences do change, and often swiftly, but the bed-rock of underlying moral values builds up and wears down very slowly, almost imperceptibly over the span of one human life. A moral man is always grounded on that fact of life. And not so very incidentally, gentlemen, I remind you that this is what Hitler and Stalin forgot.

To illustrate the point concretely and pragmatically from an example which is always of more than academic interest to young men, it might be noted that in the matter of unchaperoiied relations between the sexes, not to speak of female dress, the spectrum of moral standards and good taste has shifted quite drastically even since the flaming youth era of my undergraduate days. You are now at the stage in your biologic growth where today's standards of moral restraint in the relationship of the sexes may seem to you, as such things have seemed to many others at your age, to be arbitrary and senseless. Individuals, and, indeed, some experimental societies, have from time to time proceeded on the assumption that the individual could be a law unto himself in these matters. And yet, so far as I know, no experiment in freedom in matters of sex has ever escaped reckoning with the demands of responsibility which go with the fact of the family relationship.

Here, as in most other matters of morals, there is a hard and permanent core of individual responsibility at stake: unless and until a person is both able and willing to bear the full consequences of his or her conduct, there are deep-rooted considerations of fair play and practicality which must be protected by both the moral and civil laws of the group.

The same moral core of individual responsibility is at stake in the long effort of all societies to deal with the problems of intoxication and drug addiction. Any man who forfeits his dignity as a human being and who exposes others to the caprice, or worse, of his self-inflicted irresponsibility raises a moral issue as between himself and the civilized group to which he claims to belong.

I trust it is manifest to you that college is not the point in a man's growth where he first learns of the main moral boundaries which exist in this society. If the family, school, and church have not provided a boy with that knowledge, his presence here as a young man is a sad mistake. Let us be clear about it, the fewer such men we equip with the powers and appurtenances of higher education, the better off we'll all be.

But, gentlemen, this is the point in any young man's life where he begins in earnest to learn the weight of things for himself. The burdens of responsibility now shift rapidly from the shoulders of your parents and teachers to your own back. Whether it be at college, at work or at war, the central moral lesson taught in the curriculum of life at this stage in growth is that free man is answerable because he is free. That, I think, is the root meaning of responsibility. You have heard that experience is the best teacher. In this respect it is the only teacher. The terrifying truth is that young men learn responsibility by being permitted some opportunity to be irresponsible. Your task from here on is to use your opportunities of choice to build into the fibre of your experience the strength of moral choices.

Lest this all sound either too pat or too pious let me just remind you of the ironical fact that higher education often seems to make at least some moral choices much more difficult than they would otherwise be. Higher education takes you into those mysterious lands where there is always something else to everything. The deeper one penetrates into these complicated and perplexing areas of life's experience, the less help he gets from the advice which the mountaineer father gave his daughter as she left home for a career in the city: "When in doubt, do right."

And yet, gentlemen, despite the fact that many things do become more relative as you know more about them, it is also true that as you grow in understanding, the greater becomes the importance of what you earlier dismissed as merely differences of degree. You then begin to understand that although things are not often either black or white, the prevalent grays are facts only because black and white exist. You also then begin to understand that a sense of direction, and, as I've said, matters of degree, are mighty elements of measurement in judging the goodness of a man.

IN speaking of the moral factors in growth, I ventured the view that one of the central lessons taught by life is that a free man is answerable. That assertion itself frames the query, answerable to whom or what? Here is life's oldest and largest question. To answer it is to define one's relation to the universe; to state, at least for oneself, the spiritual terms on which life is accepted and death is faced.

The spiritual dimensions of life vary greatly from individual to individual within the same society and even within the same religion. This variety in the spiritual response of individual men is still only very imperfectly understood in our studies of man's behavior, and in view of the fact that very few of us ever stand spiritually naked in the presence of others, it seems to me unlikely that we shall ever fully understand the role of the spirit or of the spiritual in the affairs of men. And, unless I am entirely mistaken as to the nature and the place of these factors in the growth of a man, that is the way it ought to be, as well as the way it is going to be.

Although I am chiefly directing my remarks today to the spiritual in the specific sense of man's relation to his Maker, I think it may be helpful to remind ourselves that that intangible thing which we call the spirit of a man or the spirit of an institution made of men is" one of the grandest and most precious realities of human life. To borrow his informal words from a talk with Robert Frost, "When the spirit dies, the world grows false." I am sure he would be willing to join me in the further thought that where the spirit has never dwelt, there at best is an empty thing, be it a man or an institution. Parenthetically, let me be immediately relevant and ask you to believe that as you grow in understanding of whence came the Dartmouth spirit, you will come to know as you could in no other way the wherefore of this College and its greatness.

It is not the business of the College, and it is assuredly not my intention, to intrude on the established religious beliefs of any person. It must, I think, be left to each individual at all times to decide for himself where he stands on matters of faith. There is, however, the opportunity now as there always has been in the independent liberal arts college for men of sincerity to consider freely all subjects of human concern, and there must be room in this consideration for those who seek growth and strength through honest reexamination either of their beliefs or of their doubts.

I have said that it is not the business of the College to intrude on established religious beliefs, but it is due you to say that it is the proper business and, indeed, the duty of the College to intrude on any student's indifference to the moral and spiritual ingredients of a good life. I think it is fair to say to you that this is neither novel nor merely personal doctrine. It is the traditional position of a College which through the years of nearly two centuries now has never lost touch with the creative spiritual purpose of its founding by Eleazar Wheelock.

LAST June the Board of Trustees formally and tangibly affirmed the perpetual concern of the official College for advancing the moral and spiritual growth of all who seek their higher education at Dartmouth. At that time the Trustees of the College established the William Jewett Tucker Foundation, as stated in the resolution of the Board, "for the purpose of supporting and furthering the moral and spiritual work and influence of Dartmouth College." The Foundation starts with a small allotment of funds previously given in memory of Dr. Tucker, the ninth President of the College, who led Dartmouth to the promised land of contemporary greatness at the turn of this century.

A committee of faculty members under the chairmanship of Professor Francis Childs is already at work planning a program for the Tucker Foundation, and we hope that within this year the impact of its influence and of your interest may both begin to be felt on this campus. I am confident that as the support of widening interest and adequate funds come to the Tucker Foundation it will play a role of central significance in keeping the long future of Dartmouth both straight and strong.

I want to say just a word to you about the man from whose life and leadership this Foundation largely takes its meaning and its purpose. Dr. Tucker graduated from Dartmouth with the Class of 1861, and after serving as pastor, professor of theology and a Trustee of the College, he reluctantly, out of a sense of personal duty, in 1893 acceded to the summons twice pressed on him by the Trustees to accept the Presidency of Dartmouth College. He resigned in 1909 because of poor health after accomplishing nothing less than the founding of the modern Dartmouth and the founding of her ancient glory and greatness which he happily lived to see brought to fruition far beyond his dreams under the inspired and inspiring leadership of his disciple, the President Emeritus of this College, Ernest Martin Hopkins.

It is not possible on this occasion to characterize Dr. Tucker except in the most sweeping words, but of this we can be sure, he was truly a moral man who possessed and radiated the personal powers of spirtual vision, courage and conviction. A man of God, who as a teacher was subjected to trial on a charge of theological heresy, he has left us a heritage of goodness and strength. I hope you may know him a little better from his own words about the religion of an educator:

"The most dangerous thing about education, that which every educator fears most, is the perversion of power . .. the danger is imminent all through the process of education, increasing perhaps to the last. So that the emphasis falls increasingly upon rightmindedness. How to keep the advancing mind free from conceit and arrogance, humble enough to do its best work; how to keep the mind sane and reasonable under the incentives to narrowness, or prejudice, or strife; how to keep the mind free from the dominion of the low and sordid desires of avarice and greed, or the vulgar passion of vanity as expressed in the craving after money for display, or from the higher and more subtle ambitions which point the way to a refined selfishness; how to keep the mind, not the heart alone, accessible to the wants of humanity; how to keep the mind unclouded for the open vision of God,—"

Gentlemen, these are today, as they were; for Dr. Tucker's Dartmouth, and as they will be for all the Dartmouth future, "the moral problems of the higher education." I know of no better place for facing and sharing these problems than here on Hanover Plain where both figuratively and literally a man of humility or faith may lift up his eyes unto the hills for "the open vision of God" of which Dr. Tucker spoke and the help of which the psalmist sang.

And now, men of Dartmouth, as I have said on this occasion before, as members of the College you have three different but closely intertwined roles to play:

First, you are citizens of a community and are expected to act as such.

Second, you are the stuff of an institution and what you are, it will be.

Thirdly, your business here is learning and that is up to you.

We'll be with you all the way and "Good Luck!"

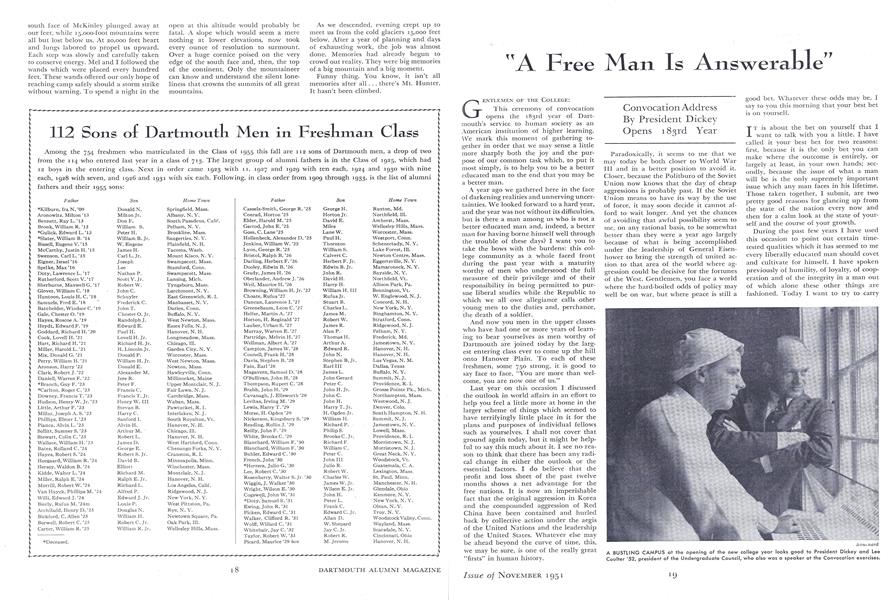

A BUSTLING CAMPUS at the opening of the new college year looks good to President Dickey and Lee Coulter '52, president of the Undergraduate Council, who also was a speaker at the Convocation exercises.

AN OVERFLOW AUDIENCE ON THE CAMPUS HEARS THE PRESIDENT'S OPENING ADDRESS

Convocation Address Opens 183rd Year

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1951 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

November 1951 By John Hurd '21 -

Article

ArticleTo the Top of McKinley

November 1951 By JERRY MORE 52. -

Article

ArticleMore Bone and Sinew For a Growing College

November 1951 By NICHOL M. SANDOE '19 -

Article

ArticleAmbrose White Vernon

November 1951 By DONALD BARTLETT '24 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

November 1951 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND

Article

-

Article

ArticlePALAEOPITUS PUBLISHES DECLARATION OF POLICY

November 1923 -

Article

ArticleLIBRARY COMMITTEE AGREES ON BUILDING SITE

March, 1926 -

Article

ArticleBASKETBALL

APRIL 1973 -

Article

ArticleRower Record

OCTOBER 1999 -

Article

ArticleIS TITO COMMUNISM'S LUTHER?

April 1950 By JOHN CLINTON ADAMS -

Article

ArticleThayer School

October 1942 By William P. Kimball '29