ON a cold day in 1904 President Tucker and his young assistant, Ernest Hopkins, were conversing as they walked along a Hanover path. They were discussing the installation ceremonies of Ambrose White Vernon as pastor of the Church of Christ at Dartmouth College. Mr. Hopkins, scion of a Baptist manse, asked if in the Congregational Church it was not customary for the local conference of churches to appoint a committee of their clergy to examine the new pastor in his theology. "Yes, it is customary," said President Tucker, "but in this instance it is perhaps just as well that they dispensed with it, because by the time Vernon finished with them they would have been uncertain whether the front of this church was graced with pillars or minarets."

Forty-seven years later, Dr. Vernon, Emeritus Professor of Biography at Dartmouth College, died at his home on Downing Road while playing bridge. There lay behind him full years of preaching, lecturing, writing, teaching, and friendship throughout this country and, indeed, other countries. But Dartmouth is able to claim Dr. Vernon's resident service for more years than any other institution, whether church or college. Eleven years is the total of his active years in the faculty, and it may be symbolic that he did not in himself suggest permanence but quickening, not tradition but adventure, not acquiescence but enlistment, not circumspection nor even discretion, but rather a penetrating vision which rebuked tradition, rest or convenience. The truth—God's truth—must be searched out and pursued by any one aspiring to the title of Man.

In his earlier days as a Congregational minister he not only employed the scalpel of "higher criticism" in his devotion to Biblical scholarship, but he directly attacked the intellectually timid in his first book, The Religious Values of the OldTestament. "The greatest evil of an infallible Bible," said he, "is the worship of a trivial God." The ruthless examination to which he then subjected a Jeremiah resulted in an actual, almost breathing Jeremiah, firmly attached to the history of his own time about which he yearned and roared. Thus the very nature of prophecy stands forth. So searching is the comprehension that the prophet is not garnished by imagination but hewn out of the solid rock of fact.

The Dartmouth of 1904 to 1907 knew Vernon as a keen competitor at tennis, as a vivid pastor of her elder sister, The Church of Christ, as a mountain climber, a disconcertingly honest scholar, and as a teacher of Biblical literature who was not a little inconvenient because he exhibited, invited, and exacted hard work and plenty of it.

From Dartmouth he moved to the Professorship of Practical Theology at Yale Divinity School for two years, and then to the pastorate of the Harvard Church in Brookline, Massachusetts, where he remained from 1909 to 1918. This pastorate was remarkable for many things, none of them restful except the hospitable home which Mrs. Katherine Tappe Vernon maintained with a warmth and energy equalled only by the warmth, energy and devotion with which she criticized his sermons.

A preacher who showed the sensitivity and skill to match his industry, he Was also a constant and interesting pastoral caller. He had that rarest of capacities, the ability to bring comfort where it was needed, because he desired to bring comfort and because he was intelligent.

If his honesty was sometimes disconcerting, so was his change of mind when convinced, especially in those most vigorous years. Dr. Henry Sloan Coffin, with whom he edited Hymns of the Kingdom of God, has well said of him, "His opinions are held with zeal and tenacity, but he is open minded if you can bring him any additional light." The gadfly quality of his preaching was not its only characteristic. He exacted of himself a meticulous craftsmanship, one reason for the small number of his books. But nothing could be more gracious than such sermons as the one on "Sosthenes Our Brother"—that Sosthenes who was amanuensis to the weak-eyed Paul, and helped Paul to accomplish Paul's mission in Paul's way, and earned the appelation "brother" from one of the mighty souls of history.

One would expect of such a man the intransigent liberty of conscience which was notable, but this never dimmed his loyal churchmanship. No matter how petty or unprepossessing might be the individuals within the fellowship, he knew that he needed, and he knew that he loved corporate worship. This conviction never failed, nor did his love of company in sport, the theatre, music and even scholarly exploration. One observes in the file of biographical questionnaires in the Alumni Records Office that he wrote a bold "None" in the space given to societies, associations and fraternities. But who was more loyal to the Tucker Fellowship which he helped to establish at Dartmouth? Who like him annually invited all his students, if they should remain in Hanover, to Thanksgiving dinner, lest they should be alone? Who so begrudged the loss of a moment of bridge if one were tardy? And be it added, he demanded just as much of Rabbit Maranville of his favorite Braves as he did of his own writing. He distrusted the extempore speaker as he distrusted the unperfected athlete.

The pastorate at Brookline was constructive and dynamic, but it broke upon the rocks of war with Germany. For a man who had grown from Princeton undergraduate and Union Theological student to scholar at Halle, Berlin, and Gottingen; who also had found his almost perfect complement in the lovely Harz Mountains; for a man who recognized but one master, namely Jesus, those were not good times. It is doubtful if any man ever hated tyranny and brutishness more than he, for his subsequent hatred of Hitler was Promethean. But his political loyalties in 1917 were more like those of his intimate friend Woodrow Wilson than of the Ku Klux Klan, and his solicitude for the innocent interned Germans was not always tactful in an angry society, nor, one must hazard, entirely shrewd. When the break came in 1918, of course odium theologicum was obtruded into the scene, and Willard Sperry is said to have remarked impatiently that here was "another instance of a heresy trial with one Christian present." This was a bitter defeat and Dr. Vernon never minimized it, but he did not dwell upon it or grow sour. He went on.

The decision to inaugurate the teaching of biography, however logical in retrospect, was not so simple as it has been told. The rare combination of scrupulous truth with vividness, coupled with the conviction that all philosophy is sterile unless wedded to human life and action, points clearly to the biographical interest. But it was not merely that biographical illustration was part of his stock in trade, for there was in him the burning conviction that there is divine purpose for human life far higher than creed or formula, if we can but find it, that there are many paths up the mountain, and that true men in their search for the truth and the heights must choose their own paths. In this he seems to have believed that Jesus Himself laid such a duty upon his followers. "Wisdom is justified of all her children." It made little difference to him whether Jesus was born in Bethlehem or Nazareth, let the critical chips fall where they may. Love and the search for the Will of God was the message the Master brought to men. "Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart and with all thy soul and with all thy mind and with all thy strength." The minds of men differ as their muscles and their finger prints, but if they are ever effective human beings they must ultimately choose a path and a purpose and cleave loyally to that commitment or they become tramps. "Biography keeps the highest crown," he said, "—a crown of thornsfor those who were progressive in spite of themselves, and not for those who took the bit in their teeth and went on to disaster. For reverence is the highest and most indispensable virtue of man." Hence we found Jeremiah, the reluctant prophet, and Paul, the erstwhile Pharisee, among his most masterly presentations, and by contrast John Brown, Alcibiades, or Mirabeau.

So it was not only a single remark of Mrs. Vernon's, nor the probably earlier suggestion of another dear friend, but the cumulation of his life that led to his latter-day venture in the teaching of biography. His mind was hot with vital conviction, the steel had long since been proven sound, and the combination of heat with the cold shock of personal defeat had put a temper in it which, with the whetting of Gamaliel Bradford's friendship, made the blade ready to cut a new path in American education. Opportunity offered in 1919 when Dr. Cowling invited him to Carleton College, and with the aid and backing of a devoted parishioner of Harvard Church he made the venture immediately significant. Students were not only excited, but they worked. They worked because Dr. Vernon made it worth while to work, and because he insisted that they make up their own minds, not sponge up "opinions." "I want you to bring me an opinion you are ready to defend."

President Hopkins was not content that Dr. Vernon should remain away from the College which had known him before and could again utilize his stimulus among the orthodox disciplines. In 1924 Dr. Vernon came, and for eight years continued his meticulous preparations, his searching questions, his absolute silence during class debates, and the long and well-nigh illegible commentaries on every single paper, paragraph by paragraph, always asking for evidence.

After his retirement, and after much of the zest for life was lost with the death of his beloved Katchen, Dr. Vernon's mind retained its keen temper and its refreshing ability to surprise with justice. An instance of this was the paper he wrote for Professor Wilson's "Components of Democratic Thought" in 1940, on the contribution of Christianity. Jesus' utterances were first demonstrated not to be democratic at all. What is democratic about "I am the way of life"? This was interesting from an elderly clergyman. But by the end the demonstration was even more compelling that Christianity in its primitive Origin established the sacred integrity of the human soul in the minds of Western Europeans with a potency of conviction unparalleled in history. To the Greeks nonsense and to the Jews a stumbling block, but to mankind the warrant of Liberty.

There is not space nor indeed any need for reminiscence. The missionary friend who amid the chaos of earthquake in Japan was enabled to do something about it by a large money order cabled from Wernigerode am Harz, signed "Love, Vernon," could suggest the direction of much reminiscence.

Though his classes were well elected, they never reached a hundred men. But there are those who remember his baccalaureate sermon in 1929, and they recall the very title so characteristic of the man: "Take the Nobler Risk." Love and truth are worth taking, nay, demand taking risks for. He cited Plato's two steeds which every mortal man must harness to his chariot: the heavenly steed and the earthly. Faith and Doubt make up a risky team, but Ambrose Vernon drove them handsomely.

Any institution devoted to the enlargement of minds and the search for truth must be composed of many factors and divers personalities. Even so simple a thing as a loaf of bread has its many components. A score of institutions have been enriched and enlivened by his intellectual and spiritual vitality, but Dartmouth College has especial reason for her gratitude in the richness of the wheat and the liveliness of the yeast which Dr. Vernon's presence supplied to her loaf of learning.

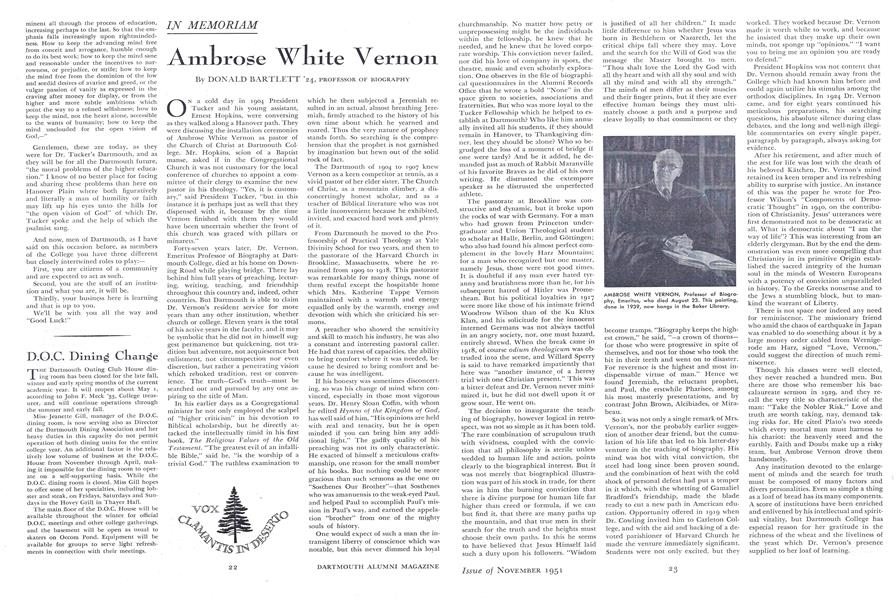

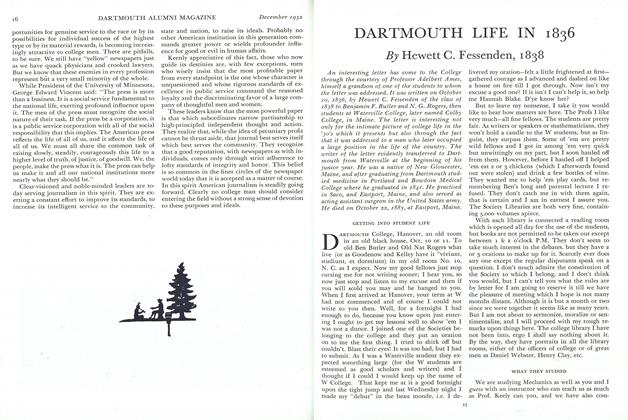

AMBROSE WHITE VERNON, Professor of Biogra- phy, Emeritus, who died August 23. This painting, done in 1939, now hangs in the Baker Library.

PROFESSOR OF BIOGRAPHY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1951 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

November 1951 By John Hurd '21 -

Article

ArticleA Free Man Is Answerable

November 1951 By President Dickey -

Article

ArticleTo the Top of McKinley

November 1951 By JERRY MORE 52. -

Article

ArticleMore Bone and Sinew For a Growing College

November 1951 By NICHOL M. SANDOE '19 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

November 1951 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND

DONALD BARTLETT '24

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS TO THE EDITOR

March 1934 -

Books

BooksADVENTURES IN BIOGRAPHY.

November 1956 By DONALD BARTLETT '24 -

Feature

FeatureCULTURAL CATALYSIS

December 1961 By DONALD BARTLETT '24 -

Books

BooksPARNASSUS CORNER: A LIFE OF JAMES T. FIELDS, PUBLISHER TO THE VICTORIANS,

FEBRUARY 1964 By DONALD BARTLETT '24 -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN JAPAN AND THE ORIENT INCLUDING HONG KONG, MACAO, TAIWAN AND THE PHILIPPINES.

JUNE 1964 By DONALD BARTLETT '24 -

Books

BooksCHARLES FRANCIS ADAMS JR. 1835-1915: THE PATRICIAN AT BAY.

FEBRUARY 1966 By DONALD BARTLETT '24