WONDER LAKE lies 170 miles north of Anchorage, Alaska. There, on June 20, 1951, I had just finished a letter home:

"It seems hard to realize that tomorrow we will leave civilization and start the last and most important leg of a trip that has been over a year in the planning. From the front of our cabin which is about 2,000 feet in elevation, the tundra stretches for 15 miles to the small hills which form'the base of the mountain. These hills are about the size of the 14,000-foot peaks in Colorado. Behind these hills a gleaming white pyramid soars 20,278 feet above sea level in a fantastic jumble of ice crevasses and vertical glaciers. This is Mt. McKinley rising higher above its base than any other mountain in the world. The northern face is almost vertical, and it is beyond belief and certainly beyond description to tell you how a 17,000-foot face of a mountain looks from only go miles away."

Yes, we wanted to climb McKinley, but a thousand problems lay between this wish and the accomplishment.

Barry Bishop '53, a former Dartmouth student and member of the Dartmouth Mountaineering Club, and I began to plan during the summer of 1950. In Denver we talked with Dr. Henry Buchtel '28, vice-president of the American Alpine Club. He told us that he had been thinking seriously of such a trip for some time and suggested that we also talk to Dr. John Ambler whose son Sterling ('53) had attended Dartmouth.

Such an expedition requires sponsorship, so we turned to Denver University. They were willing to serve in this capacity and sent Mel Griffiths, a geographer and geologist, who made the fifth member of our group.

By Christmas plans were fairly well developed and we started the tremendous but extremely important task of selecting food and equipment.

During the spring I made several trips to Boston to visit Dr. Bradford Washburn, Director of the Boston Museum of Science, who had climbed McKinley twice beforea good record, for only six expeditions have reached the summit. He told us of the —30° temperatures which were common during the summer nights and of the terrible storms with winds of 100 miles per hour. For fifteen years Brad had believed that the mountain might be climbed from the Kahiltna Glacier on the western side. Aerial photographs were his only guide, for no human being had ever set foot on the head of the Kahiltna. All previous ascents had been made from the northeast, up the Muldrow Glacier to Karstens Ridge, which led to 18,150-foot Denali Pass separating the north and the south peaks. The new route, however, would be virgin territory, so a scientific program was outlined to include work in geology, glaciology, mapping, and climatology.

Much to our delight, Brad was finally able to make the necessary arrangements so that he could accompany us. He then wrote to Capt. William Hackett, stationed in Alaska, who climbed McKinley in 1947. Bill is the only American ever to ascend the mighty Aconcagua, 22,900 feet, highest mountain in the western hemisphere. He had just returned from Africa where he had climbed the highest mountains on that continent. Jim Gale formed the eighth member of our party. Jim had also reached the summit of McKinley in 1947 and is now a civilian consultant in arctic survival for the 10th Rescue Squadron.

Now our party was complete and seldom has there been an expedition with so many members with practical experience in the type of mountaineering that we expected to find.

We had high hopes of a successful trip. Contrary to common belief, a successful expedition is one that attains its scientific objective and returns its members in good health. If the summit can be reached during the trip without undue danger to the climbers, then the expedition has achieved an extra. With most mountains, the climbers are fairly certain that they will reach the top, but with the mighty giants of the Himalayas, and the lofty snow-covered peaks of the Andes and Alaska, this is seldom the case. As in almost any sport there is danger, but these mountains confront the mountaineer with many unique problems. Just to stay alive at these great altitudes involves a constant battle with violent storms and sub-zero temperatures; the rarified atmosphere causes even the simplest movements to become exhausting work. Thundering avalanches and hidden crevasses are always present and can completely wipe out an expedition. Such mountains are usually situated at great distances from civilization, and this presents complex problems in transportation and communication. Expeditional mountaineering in such circumstances requires the best climbers that can be gathered, and safety must be paramount in the minds of all. Since few men in a lifetime are exposed to such conditions, the mountaineer who accompanies such an expedition usually feels that he must give his maximum, because of the party—and, especially, because of himself. There are few who can realize the tremendous driving force that pushes a climber on, even after his body has all but given up and his brain, so numbed by lack of oxygen, fails to warn him to turn back.

During the spring, I made list after list, trying to think of each and every item of equipment that would be needed. Spring vacation was spent in Ward, Colorado, with Gerry Cunningham, who supplied us with most of our equipment. Gerry had previously helped to equip the HarvardAndean expedition and the 1950 expedition to Mt. Everest. Three hundred mandays of food were sealed and then packed in cartons to withstand free-fall air drop. Each meal, complete with vitamins, protein, salt, candy and over 5,000 calories was sealed in a polyethelene sack. Much of the food was pre-cooked and dehydrated, so that our food weighed less than 3 lbs. per man-day. This revolutionary method of food packaging greatly reduced weight and made it extremely simple on the mountain to provide a party with light, easy-to-prepare food which could be distributed with much greater efficiency than single items of food in bulk form. At the same time Gerry constructed special packboards Of spring steel, nylon rucksacks, Byrdcloth parkas, sleeping bags, and many other items, some of which were to be tested for the first time.

In Denver, Henry Buchtel covered such important problems as finance and sponsorship while Brad Washburn made arrangements for the Air Force to drop all our food at the base camp.

At last the planning stage was completed, and by plane, train and automobile the various members converged on Seattle, the jumping-off place, where equipment and supplies had been gathered. Then up the British Columbia coast past Mt. Fairweather, St. Elias, and Logan 1,400 air miles to Anchorage. Here the full party was assembled for the first time.

To carry out the scientific program the party split into two groups. Four members flew to Lake Chulatna, and then on to the Kahiltna Glacier one by one. The other four traveled north by train to McKinley Park Station, then by truck to Wonder Lake.

At Wonder Lake, in the very shadow of McKinley, we wrote letters while awaiting the pack horses that were to take John, Mel, Barry and me to the west side of the mountain.

Just after dinner on June 21 we heard a plane and rushed out to see Dr. Terris Moore coming in for a landing. We were all so surprised that we stood there with cameras at our sides; he was using a bumpy, narrow, dirt road only 300 ft. long as a landing strip. His plane had skis that could be lowered when he wished to land on snow.

Terry Moore, president of Alaska University, acted as our pilot and gave us invaluable aid during the entire expedition. He is an unusual college president by any standards. Not only is he an excellent bush pilot, but he also climbed McKinley in 1942. Nor is this monarch of the north his highest ascent, for in 1932 he climbed Minya Konka, 24,500-foot peak in the Amni-Machen range of southeastern Tibet.

Terry, over a cup of tea, told us how he managed to fly Brad, Henry, Jim, and Bill from Lake Chulatna to a point some 7,500 feet high on the Kahiltna Glacier where they set up a temporary camp. The next day he returned and moved the entire party up to about 9,000 feet and from there they carried all their equipment to 10,000 feet, arriving about midnight and establishing base camp. With this welcome news, Terry bounced off the dirt road and headed for Fairbanks.

More winged visitors arrived next morning as a C-47 from the 10th Rescue passed overhead. We had hot tea waiting, but they seemed to feel that they needed 3,000 feet of airstrip and dropped us a message instead. This note stated that a very successful air drop of all our food and equipment at base camp had been executed that morning.

By noon of the agrd we were on our way. The horses were prime examples of biting, kicking, Alaskan fury, and a drenching rain whipping across the tundra reduced our spirits to less than zero. For three days we battled rain, roaring glacial streams, thawing tundra, and ferocious mosquitoes to reach the western flank of McKinley 70 miles from Wonder Lake.

At last the horses were left behind and we began the back-breaking job of relaying our equipment to base camp. Two days later we were established in the 8,200- foot Peter's Pass.

The next morning, Barry and I set out to place a survey marker on the summit of Peter's Dome while Mel and John cached food and gasoline on the Pass. They were then to move Half of our remaining camp to the head of Peter's Glacier where we would meet them that night. Peter's Dome is a rather gentle name for a peak that required the entire day to climb. We started on a gravel ridge which slid at every step and then on to a 50° knife edge of snow and ice. At noon we dug a small hole in the snow to gain partial protection from the savage wind while we sipped some warm tea which we had placed in our thermos bottles that morning. After a bite of lunch we continued, but the winddriven snow now all but hid the mountain and we sank up to our knees at every step. By mid-afternoon we reached the summit, which measured 10,550 feet, and placed a piece of yellow parachute silk on a pole. As it was a first ascent, Barry and I, with solemn ceremony, claimed the peak for the Dartmouth Mountaineering Club. We reached camp about 9:30 that night and piled the remaining food and equip- ment on our packs for the trek to the next camp. By midnight we found the others and gladly dropped our 75-pound packs and spread our sleeping bags on the ice for the night.

July i found us united with the other party at base camp and planning the actual assault. It was decided to split into three groups to more easily accomplish the objectives of the expedition. Brad, Bill and Jim formed the advance party and set out to establish camps one day's journey apart. Henry and John relayed food to these upper camps, thus placing medical services within call of any member. Meanwhile Mel, Barry, and I formed a team and explored the Kahiltna Glacier collecting rock specimens whenever they could be found and mapping the region geologically. The parties were in constant radio contact and the base camp usually made a call each day to one of the CAA stations in range of McKinley.

On July 10 we received word to come up, as the upper party had camps as high as 17,000 feet. For a week Henry and John had been relaying food and gasoline. Back and forth they went: 50, 60, 70-pound loads on the uphill trip, empty packs on the way down. Gasoline was indispensable, as it was used not only for cooking but also for melting snow for drinking water.

There were two snow houses connected by a tunnel and a separate cook tent at the elaborate 13,000-foot camp. A bergschrund or crevasse in the 60° western buttress served as the camp at 15,500 feet. As we reached the "Schrund" camp, we met Brad, Bill and Jim who had just climbed the peak and were vacating the higher camps to make room for us. They had placed 700 feet of fixed rope on the steep pitch above the "Schrund" which was a great help with heavy loads at that altitude. Mel and I dumped our loads and accompanied them to the 13,000-foot camp, while Henry, John and Barry spent an uncomfortable night in the small snow house nestled under the towering crevasse.

Two days later Mel and I topped the 16,000-foot ridge of the West Buttress. The clouds were magnificent and snow was constantly avalanching from the sheer sides to the glacier 10,000 feet below.

The 17,000-foot camp, located in a large snow basin just below Denali Pass, was reached by July 13. Here we met Henry, John, and Barry who had just returned from the summit that day and were on their way to the 15,500-foot camp so that there would be room for us.

Mel poked his head from the snow house early the next morning to give us a weather report. By 9:30 we reached Denali Pass where we inspected a cache left by the 1947 expedition. Henry had volunteered to climb as high as 19,000 feet with Mel and me, which was a great help to both of us. It was early afternoon when we reached this point, but we had no fear of darkness, as the sun did not set until ten and reappeared at two.

At last, late in the afternoon, we reached the crest of the summit ridge. The highest point in North America was a scant 200 yards above our heads. The tremendous south face of McKinley plunged away at our feet, while 15,000-foot mountains were all but lost below us. At 20,000 feet heart and lungs labored to propel us upward. Each step was slowly and carefully taken to conserve energy. Mel and I followed the wands which were placed every hundred feet. These wands offered our only hope of reaching camp safely should a storm strike without warning. To spend a night in the open at this altitude would probably be fatal. A slope which would seem a mere nothing at lower elevations, now took every ounce of resolution to surmount. Over a huge cornice poised on the very edge of the south face and, then, the top of the continent. Only the mountaineer can know and understand the silent loneliness that crowns the summits of all great mountains.

As we descended, evening crept up to meet us from the cold glaciers 15,000 feet below. After a year of planning and days of exhausting work, the job was almost done. Memories had already begun to crowd out reality. They were big memories of a big mountain and a big moment.

Funny thing. You know, it isn't all memories after all . . . there's Mt. Hunter. It hasn't been climbed.

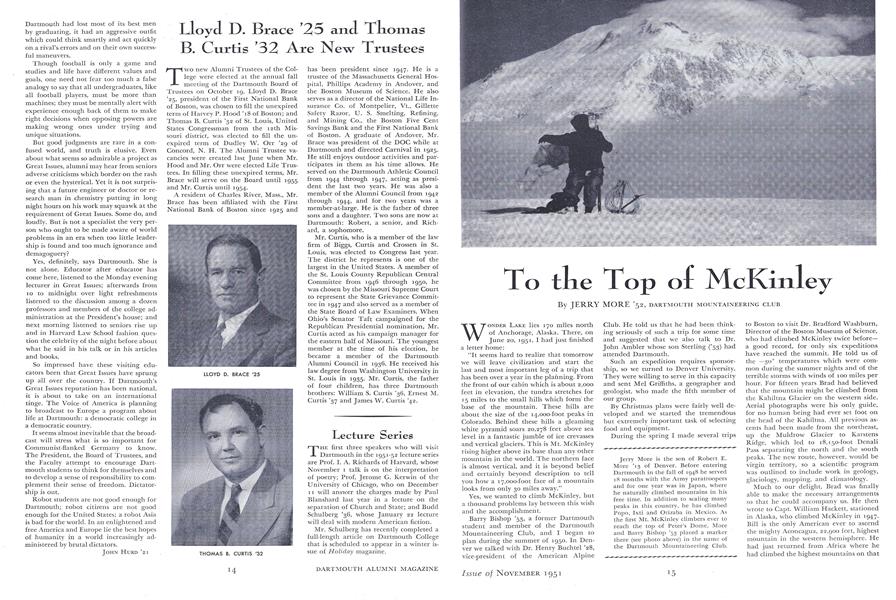

THE AUTHOR, Jerry More '52, climbing around a deep crevasse on the western face of Mt. McKinley.

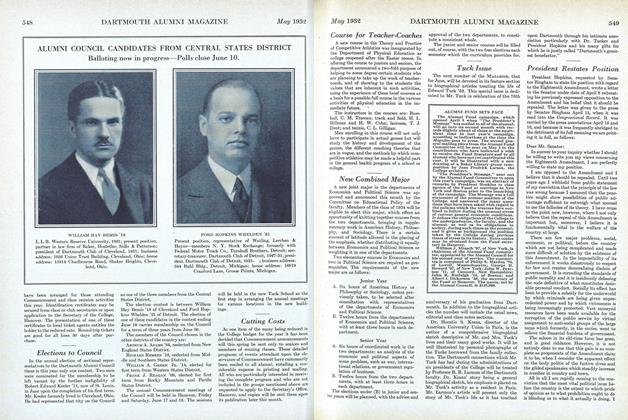

THE PARTY MAKES CAMP AT 17,000 FEET: Shown having a light meal outside the igloo-like snow house in which they slept are (I to r) Dr. Henry Buchtel '2B of Denver, Barry Bishop '53, and Dr. John Ambler.

AT 14,000 FEET: Dr. John Ambler of Denver, father of Bob Ambler '53, and Barry Bishop '53 photo- graphed by the author as they toiled upward under full packs. Mt. Foraker is shown in the background.

TIME TO BE CAREFUL: Barry Bishop '53, on snow- shoes, advances cautiously across a snow bridge.

Jerry More is the son of Robert E. More '13 of Denver. Before entering Dartmouth in the fall of 1948 he served 18 months with the Army paratroopers and for one year was in Japan, where he naturally climbed mountains in his free time. In addition to scaling many peaks in this country, he has climbed Popo, Ixti and Orizaba in Mexico. As the first Mt. McKinley climbers ever to reach the top of Peter's Dome, More and Barry Bishop '53 placed a marker there (see photo above) in the name of the Dartmouth Mountaineering Club.

DARTMOUTH MOUNTAINEERING CLUB

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1951 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

November 1951 By John Hurd '21 -

Article

ArticleA Free Man Is Answerable

November 1951 By President Dickey -

Article

ArticleMore Bone and Sinew For a Growing College

November 1951 By NICHOL M. SANDOE '19 -

Article

ArticleAmbrose White Vernon

November 1951 By DONALD BARTLETT '24 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

November 1951 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND