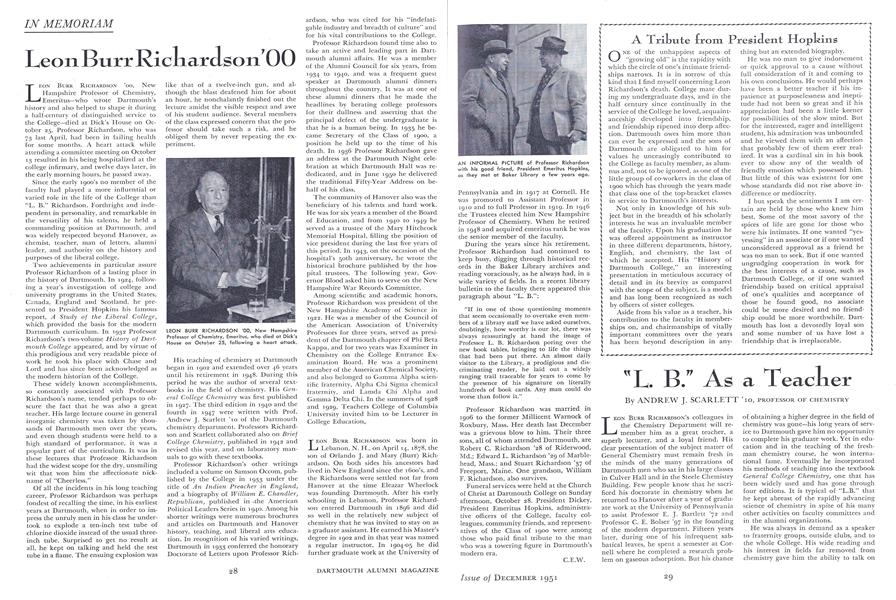

PROFESSOR OF CHEMISTRY

LEON BURR RICHARDSON'S colleagues in the Chemistry Department will re member him as a great teacher, a superb lecturer, and a loyal friend. His clear presentation of the subject matter of General Chemistry must remain fresh in the minds of the many generations of Dartmouth men who sat in his large classes in Culver Hall and in the Steele Chemistry Building. Few people know that he sacrificed his doctorate in chemistry when he returned to Hanover after a year of graduate work at the University of Pennsylvania to assist Professor E. J. Bartlett '72 and Professor C.E. Bolser '97 in the founding of the modern department. Fifteen years later, during one of his infrequent sabbatical leaves, he spent a semester at Cornell where he completed a research problem on gaseous adsorption. But his chance of obtaining a higher degree in the field of chemistry was gone—his long years of service to Dartmouth gave him no opportunity to complete his graduate work. Yet in education and in the teaching of the freshman chemistry course, he won international fame. Eventually he incorporated his methods of teaching into the textbook General College Chemistry, one that has been widely used and has gone through four editions. It is typical of "L.B." that he kept abreast of the rapidly advancing science of chemistry in spite of his many other activities on faculty committees and in the alumni organizations.

He was always in demand as a speaker to fraternity groups, outside clubs, and to the whole College. His wide reading and his interest in fields far removed from chemistry gave him the ability to talk on many subjects. His main interest was in historical and biographical books, but when he had exhausted the current volumes in Baker on these subjects, he would turn to other fields. At one time he read every book he could find on Gothic architecture, at another he read everything available on bees and their habits.

His knowledge of local and New England history was vast and his memory prodigious. A ride with him through New Hampshire or Vermont was an education in itself. Each new town or hamlet recalled to him the Honorable Hiram Blank who was born there and who later achieved fame or notoriety in the state or country. All this fund of information had been acquired by diligent research in libraries from Hanover to Washington, D. C.; the facts had been written down in longhand on cards for his files, but they were also pigeon-holed in his remarkable brain ready to pop out in an intensely interesting monologue.

He used the same method in preparing a revision of his textbook. All the available and pertinent chemical literature was read, abstracted, and penned in fine handwriting on hundreds of cards, awaiting the time when this new information would be needed in the revision to replace obsolete material in the earlier edition of his book. At least once the facts stored in his card index were out-of-date before they could be used. One hot summer day in 1945, while he was busy on the revision, he wrote a paragraph on atomic fission, stating definitely that probably no way could be found to convert mass into energy in usable amounts. He paused in his work to turn on the radio for a news broadcast just in time to hear of the destruction of Hiroshima by an atomic bomb. As he later remarked, never had scientific writing become so out-of-date in so short a time. He tore up the paragraph, and two months later wrote a whole chapter on the subject. He had obtained and digested the Smyth report on Atomic Energy for Military Purposes.

His friends often marveled at this ability to concentrate on a problem until it was finished; he could work long hours on a report, on class correspondence, even on correcting huge piles of quizzes and examinations. In his later years he tired easily, but he still managed to turn out an amount of work that would have floored a much younger man. Few have the energy to carry through such tasks as his textbook writing, his Study of the Liberal College, his History of Dartmouth College, his biography of William E. Chandler, and other work which involved so much research before the actual writing began. He was largely responsible for the planning of the laboratories and other facilities in the new Steele Chemistry Building, a labor of love for one who had endured the inconveniences of old Culver Hall, but a task which required months of planning, visits to many other laboratories, and countless details which he handled alone.

He loved to get into controversial discussions; his comments were frank and often devastating, but generally he was right. He was quick to see the fallacy in any shaky proposition, and while one could not always agree with his beliefs, one had to admit that he could unerringly spot the weaknesses in one's own pet ideas. He admired men who could argue with him, and he commanded their respect. To his intimate friends and colleagues he showed great kindness, cooperation and generosity that endeared him to all. Dartmouth lost a great teacher when he retired; we have now lost a wonderful friend whose wise counsel and assistance will be greatly missed.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

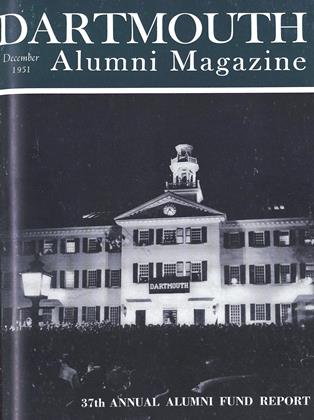

December 1951 By KARL W. KOENIGER, DONALD BROOKS -

Article

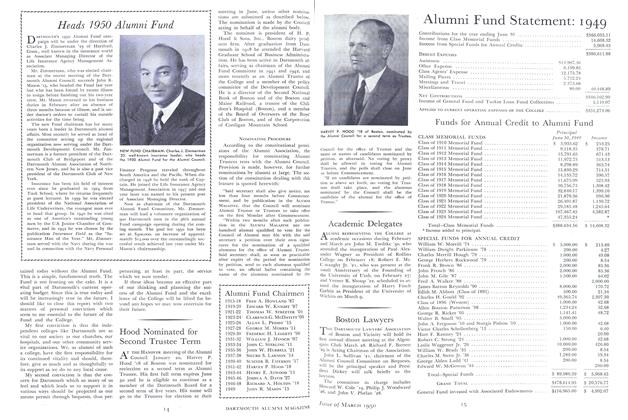

ArticleThe 1951 Alumni Fund

December 1951 By CHARLES J. ZIMMERMAN '23 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

December 1951 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, JACK D. GUNTHER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

December 1951 By ENS. SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMON J. MORAND III -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

December 1951 By HENRY R. BANKART JR., JOHN WALLACE, SIDNEY A. DIAMOND -

Class Notes

Class Notes1946

December 1951 By REGINALD F. PIERCE JR., ROBERT Y. KIMBALL