The following excerpts are the fourth in the series of reprints of chapel talks delivered by Dr. William Jewett Tucker, President of Dartmouth College from 1893 to 1909, whose personal influence on students of that period is still very much alive.

THE PHARISEE AND THE PUBLICAN IT is not easy to draw a sharp line between the good and the bad, especially between the good and the bad man—to tell how much bad there is in the good or how much good there is in the bad. This pharisee was a man loyal to his obligations, a public-spirited man; giving, as we should say, according to his means, and free from vices, but he was filled with spiritual pride. That was the bad thing about his goodness, and it was so bad that it was his condemnation. This publican was a "sinner," doubtless guilty of dishonesty, injustice and cruelty as a tax collector, a "grafter" of his time, but he repented. That was the good thing about his badness, and it was so good that it was his redemption.

In either case, however, we are dealing with the exceptional. We must be on our guard lest we form the habit of mind of dwelling upon the bad in the good, and upon the good in the bad. There is a pharisaism which goes with the bad as well as with the good. Here is a man who does wrong things, things which are confessedly wrong, but he boasts of the fact that he does not lie; he is no hypocrite; he does things in the open. He over-capitalizes the one virtue of truthfulness. There is his pharisaism. Or a man may boast in like manner of his generosity, though he never pays his debts; or of his good fellowship with men, when he might not hesitate to betray a woman. Pharisaism is the bvercapitalization of some virtue, usually the one which comes easiest to a man. It is the danger which lurks in all conventionalized forms of business or social life. If one meets the requirements of his trade, or profession, or party, or set, he makes little account of the common requirements of justice or charity, or even of good manners. The constant danger of the college man is from the artificial, the conventional. Never do as a college man what you would not do as a man. Be simply and naturally human. If you do wrong, repent of the wrong—that is the only natural thing to do. If you do right, do it modestly, with humility. That is the only way to do right. Right-doing is never at its best except as it reaches out into the unconscious habit.

March 2, 1906

PERSONAL POWER

I SPEAK to you this evening about the productive life, as expressed in terms of personal power. What I have to say is suggested by the closing words of the parable of the sower.

What is the law of increase or decline in personal power? Why is it that some men increase in personal power far more than could have been expected of them in view of the secondary powers at their command, and why is it that other men seem to lose personal power after a time and have to fall back on such secondary resources as they may have?

The first source of personal power is vitality. Vitality means more of life than is needed for the man himselfenough for himself and others. It means reproduction, fruitfulness, abundance. According to the parable, the vital seed well placed yielded nothing less than "thirty fold." Continued vitality, however, depends not merely upon natural forces, but upon the constant replenishment of "the spirit which is in man." Exhaustion is sure to follow the drafts upon resources which are not maintained. This fact is as clearly evident in respect to spiritual power, as in respect to mental power.

The second resource of personal power is sanity, or judgment, or common sense. A great deal of power is lost through misplacement. The seed which fell upon stony ground and among thorns and on the trodden way was useless. A man must learn where to cast his power to get the proper return. He cannot afford to waste it in sentimentalism, or in ill-advised action. Every man must be prepared to suffer loss, but no man ought to allow himself to suffer waste.

The third resource of personal power is the spirit of sacrifice. "Except a grain of corn fall into the ground and die," Jesus said, "it abideth alone." Selfishness is fatal to personal power. Cowardice is equally fatal. The man who is not willing to sacrifice must content himself with secondary means and agencies. He must be content to fall back upon speech, or money, or position, someone thing which may give temporary power. Personal power makes great and lasting demands upon the spirit of the man himself.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

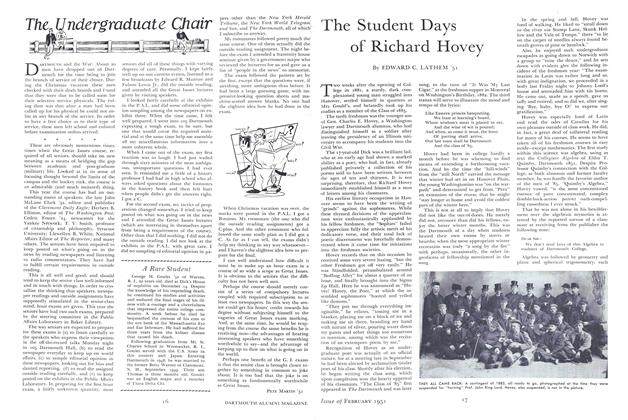

ArticleThe Student Days of Richard Hovey

February 1951 By EDWARD C. LATHEM '51 -

Class Notes

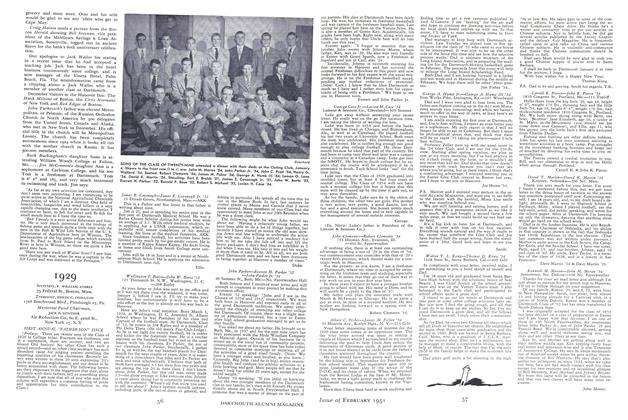

Class Notes1929

February 1951 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, JACK D. GUNTHER -

Article

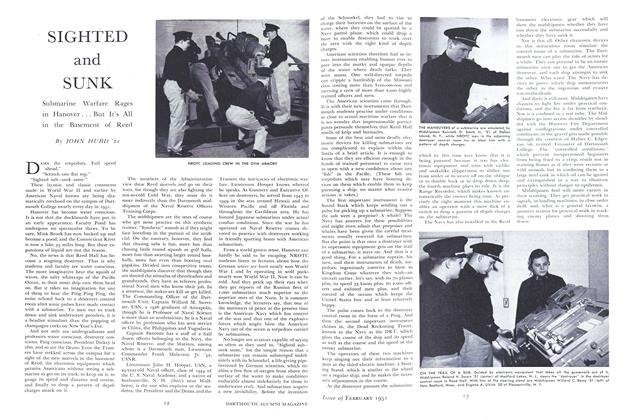

ArticleSIGHTED and SUNK

February 1951 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1951 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

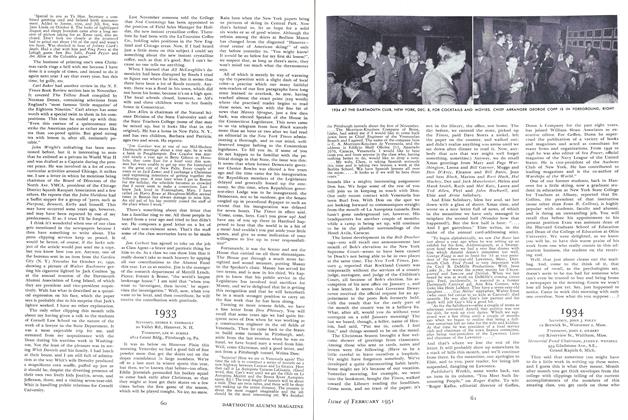

Class Notes1933

February 1951 By GEORGE F. THERIAULT, LEE W. ECKELS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905

February 1951 By GEORGE W. PUTNAM, GILBERT H. FALL