THROUGH the Folio Society of London I have received a new edition of Wilkie Collins' The Moonstone, first published in 1868. This novel is a fine example of Collins' skill in weaving a most complicated plot, creating a sinister atmosphere, and maintaining suspense up to the end. I can almost agree with Dorothy L. Sayers who calls it "probably the very finest detective story ever written," and adds that modern mystery fiction "looks thin and mechanical" beside it. T. S. Eliot calls it "the first, the longest (417 pages in this edition) and the best of the modern English detective novels. . . . Sergeant Cuff is the perfect detective."

I am enjoying a re-reading, and feel confident that most readers will also. Recent detective fiction will greatly disappoint for awhile, save the very best—let us say one in 25 that come out.

David Cecil's Two Quiet Lives I found enchanting. He writes of Dorothy Osborne (and her love and letters for and to William Temple), and Thomas Gray and his relationships with Horace Walpole, Richard West, and so on. It is a most touching interpretation of two exceptional persons whose "hearts were so civilized that they found the world (so) barbarous." Alas, they might not have found it better today.

Vilhjalmur Stefansson has a most interesting mind, and a vital and intense curiosity about everything. Like the man from Missouri, he has to be shown, and takes little on faith. I have just finished reading with some care his Not By Bread Alone, which tells of his experiments with eating a single diet of meat and fat, and how he thrived on it not only in the Arctic, but also in New York City under a supervised test for one year at Bellevue. The book has a lot of interesting sidelights, too, and I can recommend it to almost anybody.

You have probably sometime during your lives seen travelling Carnivals with their side shows, freaks, etc. Dan Mannix in a book called Step Right Up! (Harper's) gives an inside picture of such shows and of the people who work with them. He tells you the secrets of flame-eaters, sword-swallowers (Mannix got so that he could swallow a lighted Neon tube and be a flameeater, too, which is unusual for a carnival performer). He tells of the problems of a woman who weighed nearly half a ton, of Billie, a stripper who couldn't quite settle down in a small town (unlike W. C. Fields' Poppy), Flamo and how he exploded, etc. Although the book is only a series of episodes, and not distinguished either in style or form, it will entertain you.

A book which is somewhat of a jawbreaker save for the most intellectual elite (and that of course includes all of us) is Christianity and Reason, edited by Edward D. Myers, Oxford University Press, 1951. Among the contributors are two former members of the faculty at Dartmouth, my old and most esteemed teacher Wilbur M; Urban (Philosophy 3, from which in a semester I learned that the end of life is self-realization), and George F. Thomas, now at Princeton. Mr. Thomas writes on "Theology and Philosophy" and believes that faith is all-important, and Mr. Urban writes on "The Language of Theology," taken from his forthcoming book Humanity and Deity. The language of theology is not for readers of Little Orphan Annie; if you can solve Einstein's fifth (or is it the fourth) equation, or square a circle, you will be about ready for a study of the language of theology. Professional philosophers, high churchmen, and those interested in the higher reaches of the mind will find this book most stimulating.

A most charming book (four stars) which I recommend without reservation is Freya Stark's Traveller's Prelude. It is a frank and intimate picture of her family and her life before she became a great traveller in the East, and one of the greatest living authorities on Arabia. John Murray published this in London last year.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDeaths

May 1951 -

Article

ArticleBlueprinor Survival

May 1951 By WILLIAM STUART MESSER -

Article

ArticleHe Values the Rare In Books and Life

May 1951 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1951 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

Article1949

May 1951 By ROBERT H. ZEISER, DAVID S. VOGELS JR., JOHN F. STOCKWELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905

May 1951 By GEORGE W. PUTNAM, GILBERT H. FALL, FLETCHER A. HATCH

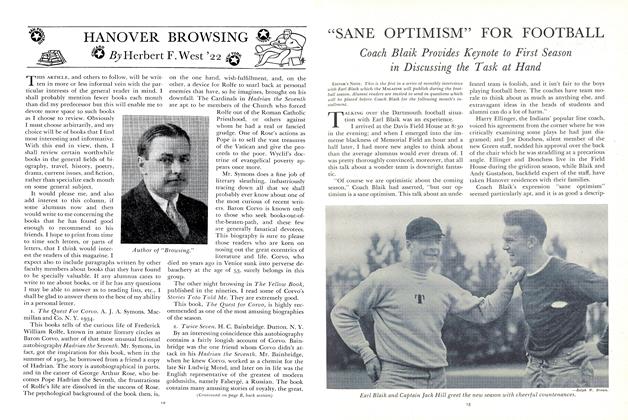

HERBERT F. WEST '22

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

October 1934 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

January 1940 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksTHE STORY OF THE MISSISSIPPI

May 1941 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

March 1943 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

February 1946 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleA Dartmouth Bookshelf

January 1958 By HERBERT F. WEST '22