IN his Life and Opinions, Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, makes this observation:

"This strange irregularity in our climate, producing so strange an irregularity in our characters, doth thereby, in some sort, make us amends, by giving us somewhat to make us merry with when the weather will not suffer us to go out of doors."

The reference is, of course, to the English climate and character, but his comment has always seemed to us peculiarly applicable to the Hanover of a slightly earlier period than the present. Either the situation does not now obtain, or these old ears are no longer as sharply attuned to latter day manifestations of undergraduate squirrelishness; but it might be reasonable to surmise that with improvements in transportation and communication the need for self entertainment is less.

In the days we are now recalling, Dutchy Hardy and Phil Trachier had the only two cars in Hanover, and local travel was by team (one or more horses attached to anything on wheels), sleigh, or pung. In winter the snow on the roads was packed down by huge wooden rollers, and made a fine surface for a sleigh race to Lebanon or the Junction, but that was for the hardy and adventurous. Wider forays, even to Northampton or New London were practically as great railway safari as expeditions to Boston or New York. The D.O.C. had not as yet created the daily call of snow-covered slopes. When the ice gnomes started marching from their Norway:, most of us simply stayed indoors.

At such times we may have had Hovey's "beechwood and bellows" at hand, but with Henry Isaacs in Greenfield as the nearest source of supply, the cup was not at the lip nearly as often as advertised. Rather were we driven to conjure up our own innocent "merriment. This might consist of anything from throwing bits of paper into the air and exclaiming, "How it snows" to inventing (and activating) the most elaborate and insidious characters from the oriental underworld. Such a one was "Wah-Tow," a malevolent crook who had an underground hideout with a secret entrance in the base of Bartlett Tower, who introduced live dray horses into fraternity living rooms, who engineered the sinking of the Vestris that the ensuing general distraction might conceal his filching of gems from Coburn's, and who consistently stole the Chinaman's steps.

Such cottage industry was fomented by a long and distinguished line of undergraduates who had a quaint turn of mind not unlike that of T. Shandy, Gentleman, himself—although they did not necessarily share his other characteristics or those of his Uncle Toby. Spunk Troy, Red Spillaine, Burglar Allison, Gene Markey, Jake Weatherby, Irish Flanigan, Craw Pollock, John Keller, John Monagan, to name but a few, kept alive the sparks of wit and inexpensive entertainment that circumvented the danger of being spiritually winter-killed.

The most difficult period, then as now, was the month of March; but each March, though seemingly longer and longer while it was with us, seems shorter and shorter in retrospect. Suddenly deep ruts would begin to crease the ice-packed roads, and there would come a day during Spring Recess, while impecuniosity held us to the local scene, when we could wander abroad over muddy highways with possibly Jay Gile and certainly a pinch bar as companions, to chop new channels in icy gutters and thus hasten the advent of spring.

And later, when white flannels supplanted brown corduroys, there would be hums on the campus, and Bones Joy and Gyp Green—or Sal and Breg with banjo and piano on the Commons porch, and senior canes, and a general sense of well-being at the closing of a year spent not entirely without benefit.

But even in the clement days of spring, the "strange irregularity in our characters" would continue to combat the disadvantages of our rural isolation. We had riots and alarms and excursions not unlike the silly springtime exhibitions in colleges today. However, the reference is not to bonfire or gunfire or sleeping on the campus (we had no panty filching), but rather to elections of Mayor, and to such dedicated bands as the "Dirty Dozen" and the "Punjab Fusileers" who organized (in strictly prescribed costume) to keep all robins off the campus between 4 and 6 a.m., or to silence all bells (chapel, alarm clock, or Inn elevator) between 7 and 10.

Probably no such puerilities would be countenanced today by the serious young men in a serious world full of wars and social and political stress and cinemas and television and convertibles. But perhaps the young men haven't changed much, or the world. Maybe even the weather hasn't changed -it just seems worse than it used to.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDaniel Webster's College Days

October 1952 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Article

ArticleThe New Dean . . .

October 1952 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

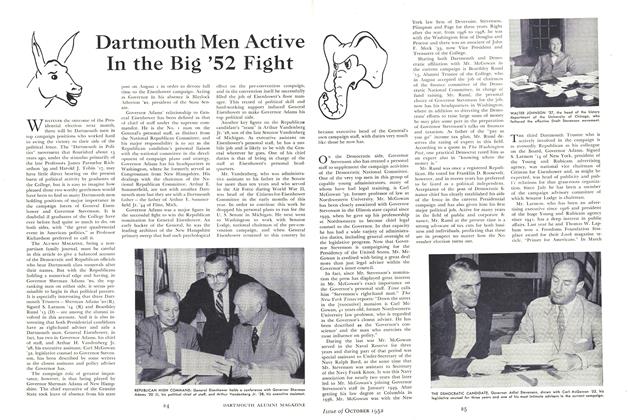

ArticleDartmouth Men Active In the Big '52 Fight

October 1952 By C. E. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1952 By ERNEST H. EARLEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905

October 1952 By GEORGE W. PUTNAM, GILBERT H. FALL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

October 1952 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR., ROBERT L. MERRIAM

Bill Mccarter '19

-

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

March 1953 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

June 1954 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

June 1955 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

October 1955 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

June 1957 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

June 1958 By BILL McCARTER '19

Article

-

Article

ArticleFACULTY ACTIVITIES

June 1917 -

Article

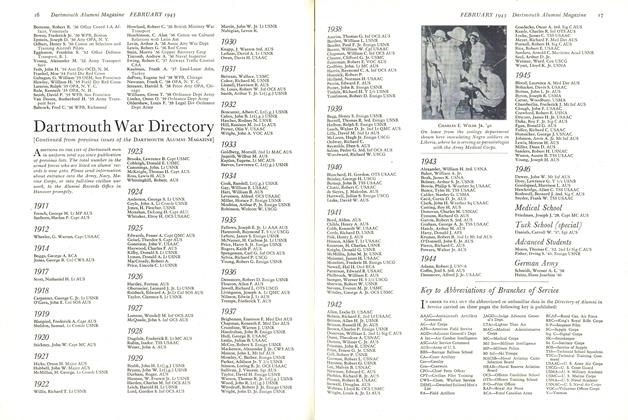

ArticleKey to Abbreviations of Branches of Service

February 1943 -

Article

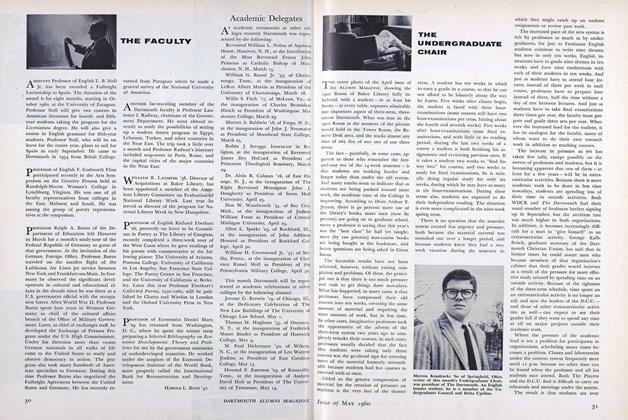

ArticleAcademic Delegates

May 1960 -

Article

ArticleBack to the Track

APRIL 1968 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

April 1960 By HARRY W. SAVAGE M'27 -

Article

ArticleWDCR Covers the Elections

DECEMBER 1962 By STURGES DORRANCE '63