SPRING has, almost imperceptibly, given way to fall, and the collegiate songsters are now offering to lay them doun and dee, not for the high-towering love of comrades or the old chapel bell, but more specifically for a greater total on the scoreboard and the confusion of the rival team. The implied intent in athletic madrigals is to return with one's shield or upon it - total victory or total demise apparently being the only options - with much store set on shouting with a great shout so that the opposing stands fall down flat. Our football songs can hold their own in these protestations, with the gratuitous suggestion that the mere hue of our jerseys is warrant of success, and the selfevident assertion that we are revisiting a locale that has been continuously inhabited by our opponents for around three centuries. An exception to the formula is Dear Old Dartmouth, the most under-weening of college songs which, far from claiming complete superiority or offering agonizing sacrifice, is merely a vote of confidence, with the ancillary suggestion of widely publicizing the College - a project that has, incidentally, been thoroughly implemented.

In general, college songs, and especially Alma Maters, run to cliches and bad rhyme. They protest undying loyalty and devotion through a future full of anticipated distress. They never depict college halls secluded in valleys but, rather, hill-top edifices camouflaged with creeping vines (hederahelix). Twilight almost invariably steals gently on hallowed walls and, while sunrises have fallen into disuse with the abolition of early morning chapel, the sunsets are riotous to behold and give token of future glory for the institution.

The rhymesters reach their zenith with the Latin nickname for "college"; and though the more discreet bury the words "alma mater" in the interior of the line, or self-rhyme them, bolder spirits (like William Ellis "who with a fine disregard for the rules. . . took the ball in his arms and ran with it') match "alma mater" against "water," "waters," "daughter," "beata," "mother," "gather," "together," "create her," "instate her," "valley, and "lady" — in fact with almost everything but "freighter" and "blotter." An apocryphal but not uncharacteristic sample of the college song might run:

"Shady Groves Institute, we love thee, Naught else will we put above thee. To thee ever we will be true, Whatever else may befall me and you. Shady Groves Institute, Hail!"

In his admirable and often quoted New Yorker piece on college chants, Morris Bishop of Cornell remarks: "Blessed among colleges is Dartmouth. Blessed in having mothered Richard Hovey. . . a true poet [who] gave his college a series of songs, rich and masculine . . . a garland which no other American college can attempt to match." To our mind, Hovey's distinctive virtue in this department, aside from his general poetic gift, is the specificness of his references. EleazarWheelock is, of course, merely a topical song; but even in such a stately and formal piece as Men of Dartmouth, he works in "hill winds," "Lone Pine," "still and silent North," and "the granite of New Hampshire." In the Hanover Winter Song, while the references are more fanciful, they still have definite (and frigid) connotations for Dartmouth men: "wolf wind, "snow drifts deep along the road," "great white cold," "wine witch, ice gnomes," and "long forgot Decembers."

When Franklin McDuffee was writing Dartmouth Undying he fretted about the problems of avoiding cliches and of being specific without being banal. Although he modestly claimed that "there is no music for our singing," he and Homer Whitford achieved what to our prejudiced ear is the most beautiful of college songs. In it there are, probably of necessity, touches of generalized natural phenomena, but the "sharp and misty mornings" stir memories in any who ever had eight o'clock classes; the bells are clanging, rather than tolling or sweetly ringing; instead of the customary marching tread, there is "the crunch of feet on snow"; and the only near approach in college literature to the nostalgic appeal of "crowding into Commons" is Ohio Wesleyan's toast "from the good old Sulphur Spring."

Through this song, unrivalled in its class, the gleaming, dreaming walls of the College remain — no matter what their architectural period - miraculously builded in our hearts.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1957 By SIR GEOFFREY CROWTHER -

Feature

FeatureOpening; Assembly

October 1957 By THE HONORABLE LEWIS W. DOUGLAS -

Feature

FeatureFinal Assembly

October 1957 By THE HONORABLE JOHN GEORGE DIEFENBAKER -

Feature

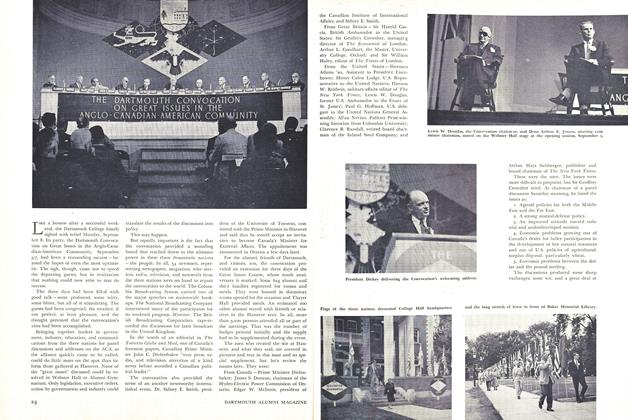

FeatureTHE DARTMOUTH CONVOCATION ON GREAT ISSUES IN THE . ANGLO – CANADIAN – AMERICAN COMMUNITY

October 1957 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1957 By CLARENCE B. RANDALL -

Feature

FeatureHonorary Degree Ceremony

October 1957 By SIR WILLIAM HALEY

BILL McCARTER '19

-

Article

ArticleNot So Long Ago .... Fires

February 1934 By Bill McCarter '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

November 1952 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

January 1953 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

February 1953 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

June 1954 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

February 1956 By BILL McCARTER '19