THEY strained forward in their seats - all 2837 of them - as the cars rumbled up out of the valley and on to the plain. Some of them were very tired, because now they were upperclassmen and could have cars of their own and they had never before realized what a sacroiliac felt like after it sat behind a wheel all the way from New York; some of them were bleary- eyed because they had told themselves at the station that they'd get some sleep and the B & M had told them all the way from Springfield that, as usual, they were wrong; and some of them were breathless with excitement, because the miles hadn't gone by fast enough and the family had stopped too long for lunch in Albany and they wanted to see their Alma Mater and get oriented because they were freshmen.

They peered through their windshields, and a mile away their welcome beamed back at them. It was Eleazar Wheelock, the same Eleazar Wheelock who had grinned at their retreating rumble-seats last June; and there he was, still bargaining with the same Indian over the same five hundred gallons of rum, and still swaying precariously atop the white spire that eternally guarded Baker's 700,000 books. But this time against a bright blue September sky.

It was an early September sky that dazzled Hanover's newest crop of pea-greens. They "saw each other around the campus" for the first time September 18. To look at, they weren't as green as their predecessors, for atop their mostly-crewcutted heads sat the emblem of a brand-new, noncoercive Orientation Program: a pure white hat with a Dartmouth green brim and numerals of The Only Class for all the world and the sophomores to see.

They sat in hushed silence as the President of the College told them that the "initiation of this program will be written down in future histories of the College if its operation is a success." Then they broke the hushed silence to stage some of the biggest and most spontaneous rallies the campus had yet seen.

But by the time the upperclassmen got back, they were all rallied out. A demonstration staged for the night of the 23rd drew less than a sixth of the class, and up- upperclassmen grumbled that "they have no spirit and they have it too easy, and besides - they look too much like Green Key men in those new hats."

But the shiny white crowns made it easy to spot the pea-greens across campus, and recruiting for furniture-carrying and rugbeating continued at its seasonal pace, slackened only by the increasing momentum of classwork. But by the end of the week the "new hazing" had slowed to a crawl, and Palaeopitus had high hopes for a rejuvenation during the Holy Cross rally Friday night of the first week.

They were almost right.

The Class of '56 built a towering conflagration and obediently chanted their class numbers, and everything looked fine until several freshmen, in the heat of the rally, tore their white hats from their heads and tossed them into the bonfire. Before the chant had gone ten more counts, two hundred hats were ashes and smoke.

Sophomores grumbled even louder at this unexpected freshman rebellion. The grumbles reached a peak as knots of 55s surged toward College Hall with malice aforethought and charity forgotten. Palaeopitus Chairman Brock H. Brower '53 mounted the balcony, but the demonstration was already too far out of hand.

It wound its way down Wheelock Street, plunged New Hampshire hall in darkness, menaced countless freshmen with a return of Vigilante tactics, and only halted when Assistant Dean Arthur H. Kiendl mounted a lamppost and asked that the noise be saved for the next day's game.

As for the orientation program, Brower says it was "enough of a success to warrant further experiments by Palaeopitus in future years." One upperclassman wondered how they were going to keep the throwing of hats into the fire from becoming a tradition.

Palaeopitus hasn't answered that one yet.

Somewhat lost in the chaos of the freshman-sophomore riot was the new Adminis- tration curfew on drinking. When people finally got around to talking about it, nobody particularly minded that alcohol was forbidden after 1 a.m., because indoor dates were illegal after that hour anyway. A few scattered gripes were registered about the "no drinking before noon" regulation, since it cut out fraternities' milk punch parties on Sunday mornings. But most agreed that the new rules were fair, and both the IFC and the College were pleased with results over the Holy Cross weekend.

College Hall's new Snack Bar and recreation center drew crowds of freshmen and upperclassmen during its first few weeks. Prices were reasonable, and the '56s were happy that they had a place to go with their dates. There was some speculation on Main Street about what it would do to the restaurant business, but no trends have yet reared their ugly heads.

Students generally drifted through the seasonal and seasonable currents of the first week of college. They listened politely to President Dickey's Convocation talk on "Manners," and took little notice of Herb Solow '53's "poison-pen" mail in response to his "I Hate Johnny Ray Club." The Theta Chi localization caused a slight flurry of excitement the first day, but by the end of Convocation it was old news. (Most sophomores seemed to like the idea, and a few national fraternities wondered whether to be envious.) The Gutenburg Bible celebration was soundly applauded by the Faculty, but most students either had no inkling of the importance of the anniversary, or just didn't care.

The first bombshell of the year was dropped on Wednesday, October 1, as TheDartmouth shouted from a four-column front-page editorial that it was for Adlai Stevenson. The average conservative undergraduate stood in his pajamas in front of his dormitory door early that morning and fumed at the incriminating document. If he was normal, he read that day's editorial with a thoroughness that was foreign and a severity that was exaggerated. And if he was able to walk and talk, he tossed aside both the paper and the pajamas and told the editors just exactly what he thought.

The Dartmouth based its case on the character of its candidate. "A militant man, wedded to a party, it declared, can rejuvenate that party and its principles and bring about the salvation of a century or a civilization." The paper cited its deflation of enthusiasm" over General Eisen- hower, and based that case on the General's support of McCarthy, Bricker, Jenner, and Dirksen. The Dartmouth declared for Stevenson because it believed that he was an opportunity to "preserve the flat bed of social progress that has been laid down in this country, and to . . . educate and elevate a people whose destiny is leadership."

Before campus reaction had a chance to burn down Robinson Hall and smash the paper's presses, a "Dissenting Opinion" appeared, authored by the Republicans in the paper's directorate. They declared:

The triteness of the o£t-repeated "it is time for a change" may well be matched only by the truth of the principle hidden in those six words, a principle that has had to become trite in order to make itself heard: that anyparty which retains power for twenty yearsusurps the mandate by which it gained control in the first place.

Campus opinion was soothed somewhat by this second statement, but letters continued to trickle in. Six Tuck School men refused to be placated, and in a bitter post- card said: "Now we know who you're for; how about taking a campus poll to find out who we're for."

The Dartmouth was glad to oblige.

The following Monday, much more soothed undergraduates said that they liked Ike, 3 to 1. Seventy-five per cent of the College voted; Eisenhower polled 1565 preference votes, and Stevenson got 528. But only 1269 thought the Republicans would win in November.

Only a few miscellanies distinguished Early Fall-1952 from Early Fall-Any Year. A Mount Holyoke graduate became a teaching "fellow" in the Chemistry Department and drew more whistles than analyses. Ralph Flanagan played in Webster Hall in competition with the first night of fraternity rushing, and rushing won. Mystery leaflets dropped from a plane on campus turned out to be scrap paper, and Smith girls overran the College during "Mountain Day and had their pictures printed, rogue's gallery style, in The Dartmouth. The line of freshmen in front of the signup desk for a Colby blind date dance was three blocks long, and the D.O.C. worked out plans to convert Carnival into a smaller, all-Dartmouth weekend.

But probably the biggest shock of the season was a small headline in October 7's Dartmouth. It read: Whale is Guest SpeakerAt Union Service Sunday Full name's John S. Whale; he's a British Congregational preacher, and one of the most inspired cetaceans we've heard in a long time.

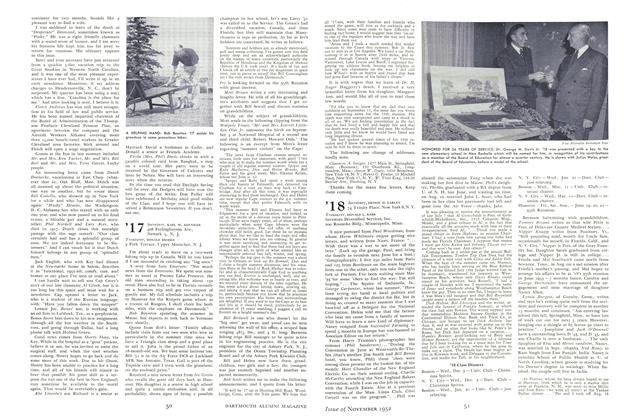

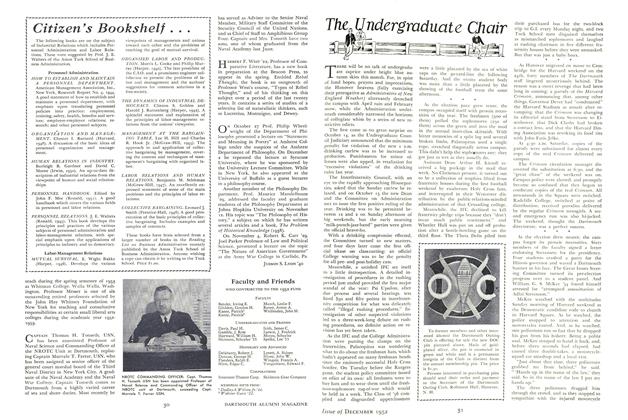

HIGH LEVEL ADVICE: Arthur H. Kiendl, Jr. '44, Assistant Dean, climbed a lamppost and so impressed rioting freshmen and sophomores that they followed his suggestion and went back to bed.

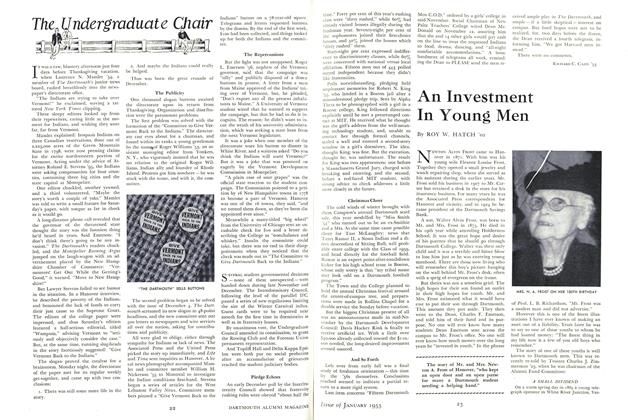

The Undergraduate Chair this month presents the first article by its new occupant, Richard C. Cahn 53 of Freeport, N. Y., who joins our staff as Undergraduate Editor. He is managing editor of The Dartmouth, a philosophy major, and a member of Gamma Delta Chi.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleOn Educational Policy

November 1952 By PROF. ANTON A. RAVEN -

Article

ArticleThe Business of Being a Gentleman

November 1952 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1952 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

November 1952 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND -

Article

Article"The Greatest Sport"

November 1952 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

November 1952 By REGINALD B. MINER, ROBERT M. MACDONALD

Richard C. Cahn '53

-

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1952 By Richard C. Cahn '53 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January 1953 By Richard C. Cahn '53 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1953 By Richard C. Cahn '53 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1953 By Richard C. Cahn '53 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

April 1953 By Richard C. Cahn '53 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1953 By Richard C. Cahn '53