Educating the Alumni

TO THE EDITOR: For the past several years I have been conducting a desultory correspondence with Dr. John Dickey regarding a pet project of mine. We have exchanged views on its pros and cons, but it still remains in the "matters pending file." Inasmuch as it is a matter that concerns all of us alumni, I am asking your indulgence and the use of your columns to pose the problem and see what other alumni might think of it.

It is my primary thesis that education is a continuing process and does not stop with the tendering of a degree that the college has a stake in the continuing education of its alumni and that the alumni, in turn, have a regard for the College and the erudition of its faculty in relation to all subjects as they continually progress and unfold.

As of today, about the only contact with the college is through the pages o£ the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, which is excellent, and through the class officers and periodic reunion arrangements. And then, of course, there is the admirable "Hanover Holiday," which unfortunately most of us cannot attend very often.

It is therefore my suggestion that a new type of publication be offered by the College to all the alumni; namely, a newsletter which would be issued, perhaps on a monthly basis, during the college year. It would be divided into various fields of the arts and sciences and the heads of departments and their staffs would be asked to contribute brief reports or opinions, or explanations, or arguments bearing on all manner of happenings pertinent to their respective fields. In no way would the material be exhaustive or lengthy, nor would it take the form of dicta from on high. I simply mean that perhaps the case in point for the department of Political Science or Economics would be "Tideland Oil." The appropriate department head or heads would state the case, both pro and con, in very concise form and then perhaps professors with differing points of view would be asked to prepare brief commentaries on it.

If the subject happened to be one concerning the new polio serum or the attack on Dr. Conant, or a new piece of music by Sessions or the matter of loyalty oaths, or whatever, the appropriate department would have it as a matter of regular assignment to supply 500 or 600 words on the subject for the information and education of the Dartmouth family.

Now, it may be argued that matters of this kind are given sufficient space in the daily newspapers and in the news weeklies of the country. I do not think that this is sufficient or even pertinent. Outside of a very few objective newspapers in the United States, most of them are knowingly or unknowingly slanting the news (as the Great Issues course clearly points out) and even more important, most of them relegate very important news to inside pages, while page one carries the story of the two-headed cow or what happened to Mrs. Jones on Main Street. The news weeklies also have their ax to grind and are not subscribed to by anything like the majority of the Dartmouth alumni. And none of them have the authority for a Dartmouth man that his college faculty would likely have. That does not mean that what Dartmouth says is necessarily the gospel, but certainly the college attitude, as reflected both pro and con, would bear real weight on the affairs of the day. I think it is extremely important that Dartmouth men and that goes for Harvard men, and Princeton men and Yale men - should be well informed because very often they are the leaders of the community and their opinions are looked up to and respected by others with whom they come in contact. A well-informed leadership group is an essential to a democracy and I am not so sure it is presently as well informed as it might be. We tend to grow lazy intellectually and tend to become colored by propaganda, prejudice and dogma; and a brief and concise and authoritative commentary from the College might therefore be very acceptable and highly palatable.

As to the mechanics, I don't see where it would be asking too much of the faculty to add this small job to their dockets and, as a matter of fact, it is my belief that the faculty would welcome the opportunity of expressing itself to the alumni, because the alumni would then be in a position to express itself to the faculty. Such a two-way street would be very healthy in my belief. Secondly, the ALUMNI MAGAZINE cannot, by its nature, perform the function I am outlining, except in very minor part. The financing of the project I think, also presents no great problem, because the format of the newsletter would be simple in the extreme and I am convinced that the alumni, or a good portion of it, will be more than willing to pay the $2 or $3 a year that such a subscription might cost. Of course, if it could be done inexpensively enough to be included in class dues, so much the better.

So that's the suggestion and I would be extremely interested in having the reaction of other alumni who would be interested enough to write their comments for submission to the College. In the final analysis, of course, it would be the decision of the College.

New York, N. Y.

Correcting the Record

To THE EDITOR: I was much interested in the article appearing in the January, 1953, ALUMNI MAGAZINE, called, "An Investment in Young Men." This certainly depicted a phase of the eariy Hanover scene which I have often heard about and which I was particularly glad to see so appropriately recorded. Mr. and Mrs. N. A. Frost were fine people, indeed, who did many a kindly thing for an indeterminate number of Dartmouth students.

On page 24 of the MAGAZINE and about in the middle of the article, there is a reference to my father, Lewis Parkhurst. At that point, it is said, in part, "He gave Parkhurst Hall to the College in memory of his son who died in the First World War." As a matter of fact, this statement is not correct, and I am sure you would wish me to note that Parkhurst Hall was given in memory of my brother, Wilder L. Parkhurst, of the Class of 1907, who died at the start of his sophomore year, which is to say, in the Fall of 1904. The building was constructed in 1910 and 1911, and dedicated at Commencement in the latter year.

I am taking the liberty of sending this letter in order that the records may be clear as to this matter.

Winchester, Mass.

Where Colleges Fail

To THE EDITOR: I apologize for picking up a controversy that is already a little stale, but the fact is I cannot forbear making some observations on the recent dispute between Mr. Cardozo and some of his fellow alumni. Mr. Cardozo asked why Dartmouth alumni present an almost solidly Republican front. Mr. Cardozo, as he himself well knew, could hardly have asked a more profound or complex question about American life and mores.

In the case of Mr. Cardozo's query it at once became mixed up in the conservative versus liberal ruckus that is being agitated with so much malice and energy and so little taste by a number of national weeklies. Mr. Cardozo, I assume, did not mean to imply that a liberal was better than a conservative, or wiser, or purer, or that the proper measure of a good education was how many "liberals" it produced. He covered that when he spoke of those conservatives whose attitudes he respected who had arrived at their positions as the result of thought and reflection.

What concerned Mr. Cardozo, and rightly so in my opinion, was that Dartmouth students, as students, but even more as alumni, slip into a broad, comfortable, pre-cut intellectual groove, marked out, for the most part, not by their own independent efforts as educated men but by the prevailing attitudes o. their business and their community - in other words, of their class. Since most Dartmouth men, indeed most college men, belong to the great American middle class, they, for the most part, react as it does; accept its catchwords, slogans, and shibboleths as their own. They do not think independently, they simply adopt the protective coloring of their class. They become "mass-men" of the middle-class. It is this fact which, if I read his letter aright, most disturbs Mr. Cardozo. It is depressing to think that after four years of expensive and rather intensive education a man can be summed up or nailed down simply by identifying the professional and social group to which he belongs. The monolithic intellectual character of the average American college graduate suggests a frightening lack of independence and individuality. So what Mr. Cardozo is deploring is not that Dartmouth (and all other American colleges) turn out an whelming proportion of Republicans, but that they turn out people unable or unwilling to make a struggle to think independently, albeit the result of such a struggle might still be "rock-ribbed conservatism."

The fact is, in my opinion, that modern education, despite all its lofty pretensions, does not teach the student to think. It does not teach him to think because it does not teach him (or encourage him) to feel to feel the mutability and variety of life and of all human experience; to feel the multiplicity of truth and what a Dartmouth professor has called "the multiformity of man." Modern education has preferred the easier way of formulas. It has undertaken to explain the fantastically complex nature of man and his society by means of stereotypes sophisticated and highly intricate stereotypes to be sure, but stereotypes none the less. In this the "social sciences" have been the worst offenders (there is more sense in referring to the "art" of physics than the "science" of history). Life and society as revealed in history are full of what Herbert Butterfield has called "tragic dilemmas," full of paradoxes and ambiguities. But the student is seldom if ever brought face to face with these predicaments in their true dimensions. He is rather given glib and glossy explanations of social mechanics and individual psychology. The result is that he can spot a neurosis but rarely recognize the human being behind it. Sidney Cox was one of the greatest teachers I have encountered in my academic experience because, among other things, he could not help but infect his students, however rigid and doctrinaire they might be, with his own passionate interest in man in all his guises and all his predicaments.

The Christian-Humanist tradition in education placed its emphasis on equipping the individual to grasp life imaginatively on as many different leveis as possible. Modern pragmatic "scientific" education has presumed to boast that it could provide the final answers to the immemorial problems of human existence. Contemporary education's effort to provide answers that would silence questions rather than awaken awe and inspire thought - have made it truly the opiate of the American middle class. "Tentative" and "humble" are words too seldom heard on college campuses today and too rarely experienced in the political disputation that the one-time student engages in as a citizen of the republic.

The formulas and dogmas taught in most colleges today are, to be sure, liberal ones, but it is easy enough, once out of college, to exchange these for another set more closely identified with ones own fancied interests and the attitudes of the boss or of the people next door. The error lies less in the particular set of ideas the individual college student adopts, than in the process by which he arrives al them. Are his ideas still capable of growth, and is he? Do they at least attempt to do justice to the terribly, heartbreakingly complex nature of the "whole truth," to include as much of the opponent's "truth" as possible, or are they unshatterably complacent, set in the curious mortar of righteous conviction that is the apparent fruit of so much of our higher education today?

This is the question Mr. Cardozo asks and the one American education must answer.

Santa Monica, Calif.

Five Paragraphs of Fantasy

To THE EDITOR: An editor can scarcely be held responsible for the accuracy of copy printed on the advertising pages so the following comments are in no sense a reflection on an excellent magazine. They are written out of fairness to the government of Canada, and in defence of a remote group of people some Dartmouth men have good reason to admire.

Page 2 of the March issue o£ the ALUMNI MAGAZINE shows a dancing Eskimo and a nondescript fish-like object, accompanied by five paragraphs of fantasy. In order from top to bottom the paragraphs discuss: i) The primitive but happy Eskimo of Baffin Island. 2) The initiation, eight years ago, of a system of family allowances for all Canadian children - including Eskimos. 3) The claim that most of the Eskimos thereupon "left their hunting grounds and moved in close to the trading posts." 4) The statement that "The Eskimos' life was soft and easy— for they had complete security." 5) An elaborate moral to the effect that "enslavement by security isn't something that happens only to Eskimos."

With some knowledge of northern Canada, a fairly close study of the Family Allowances system and the benefit of a discussion of the advertisement with administrators in Ottawa, I would like your readers to know that points (2), (3) and (4) in the advertisement are unadulterated balderdash, quite apart from approaching the libellous, and that item (1) is little better.

There has been an immense improvement in the condition of Canadian Eskimos in the past eight years, and much of the credit must go to the carefully regulated issue of suitable food for the use of children who in a less secure age would have died of starvation or disease.

To the makers of "The Amazing Purple Motor Oil" full of vigor and ambition in the "primitive but happy" surroundings of Los Angeles, five dollars' worth of Klimm, Pablum, cod liver oil and fish hooks (to catch fish at forty below) may sound like the beginning of the end of "self-reliance ... productivity and ... freedom" (see point (5). To Canadians (who pay the taxes for Family Allowances) it is just a little encouragement to those of their fellow countrymen who happen to live in a part of the homeland a trifle harsher than the pleasant cities of the south.

Should some wandering Eskimo encounter the "Amazing Purple Motor Oil" and himself on an odd sheet of your distinguished journal placed to "Stop a hole to keep the wind away" from some trading-post back-house, he might reply with the gentle courtesy for which his people are famous "iteq!"

Professor of Geography

Hanover, N. H.

No Party Victory

To THE EDITOR: Hidden among the church advertisements of a city daily is an announcement that the popular vote for Congressmen was Democrats 28,641,644, Republicans 28,379,176. The Democrats topped the Republicans by 262,468.

Counting only districts where there were contests between Democrats and Republicans, the tally was Democrats 23,710,156, Republicans 26,969,477.Eighty-two unopposed Democrats polled only 4,931,488 votes. Eleven Republicans polled 1,409,699 votes. The average for unopposed Democrats was 60,000 votes. The average for unopposed Republicans was 128,000 votes.

These figures indicate that something is rotten, not in Denmark, but with the proportions of our election system. Either the apportionment of representation is haywire or the Republicans vote very much better than the Democrats when there is little or nothing to vote about. They also indicate that election by plurality is a very inaccurate way of electing representation. Furthermore, they suggest that many Congressmen rode the coat-tail express to Washington, hanging on by the skin of their teeth. There is no doubt that the Eisenhower landslide was a personal victory and not a party victory.

If the Congressional elections had been held in accordance with Danish election laws, which provide accurate representation of the voters' votes, the Democrats would be in control of the House of Representatives.

Election methods which do not reflect the true state of the public mind are dangerous. They give hotheads of all parties and sections wrong ideas of the political strength of the moderate elements in the community. They either suppress minorities or exaggerate their strength and put a premium on infiltration of major parties. We have had one civil war, because election by plurality did not show the true state of mind of the voters on the question of preserving the Union. There is no sense in risking another from a similar cause.

Harvard, Mass.

Faculty Articles

Prof. Philip Wheelwright is the author of Philosophy of the Threshold which has been reprinted from the January number of TheSewanee Review.

The Department of Comparative Literatureat Dartmouth College, by Prof. Vernon Hall Jr., appears in the 1952 issue of the Yearbookof Comparative and General Literature.

American Forests for February contains an article A Woodsman in Washington, by Robert S. Monahan '29.

The National War College and the Administration of Foreign Affairs, by Prof. John W. Masland, has been reprinted from the Autumn issue of Public Administration Review by the National War College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

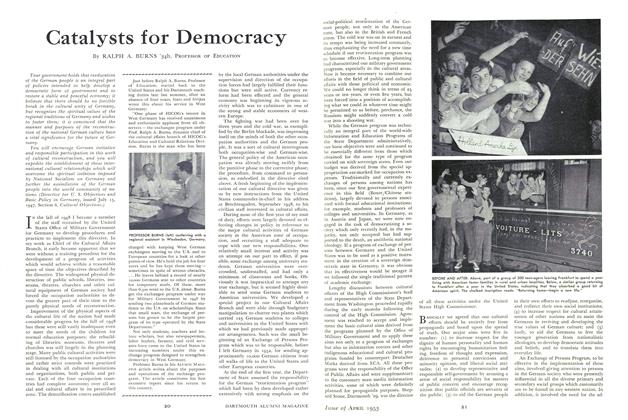

ArticleCatalysts for Democracy

April 1953 By RALPH A. BURNS '34h, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1953 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

Article1953 Alumni Fund Opens Campaign for $600,000

April 1953 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

April 1953 By KARL W. KOENIGER, HOWARD A. STOCKWELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

April 1953 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

April 1953