EARLY last month when we had finished taking down the storm windows and were ready to settle into the summer routine, we got hold of the Man with the Key and indulged a long-standing fancy for poking into some of the College's cellars and attics. A college is like a big family - enjoying the obvious defects as well as some of the advantages of that social organization - and its cellars and attics would be no surprise to the average householder. The former are apt to be filled with heavy junk, like hall trees, and the latter with light junk: piles of old Youth's Companions and Munseys and left over rolls of wall paper that will come in handy for patching.

Dartmouth boasts dozens of polite caveaux, clean, dry, painted, and filled with old furniture, packing cases, broken radiators, and academic impedimenta. In one structure the underground is bulging with complicated nautical toys for playing submarine warfare. In another a "human relations" laboratory is about to be neighbored by a zooful of psychiatric fauna. In another, a poor man's atomic pile of radio-active isotopes is sprouting. The Medical School laboratory is, like St. Peter's, founded on a rock - a sloping shelf of solid, Observatory Hill granite pushing through one side of its basement.

A non-claustrophobic Davy Jones could be quite happy in the concretelined reaches that cradle the Spaulding Pool, a hideout attained to with only a modicum of scrambling after one has outflanked the faithful pumps that mournfully squirt water and chlorine into the depths above one's head. But the most cellar-like of all the cellars is that of the Chapel, over whose uneven dirt floor and against whose low hanging beams have clomped and clonked the feet and poll of many a devout songster threading his way to the bulkhead out of which he can pop and startle the congregation with a burst of antiphonal praise from the apse.

Up above, the organ loft is as carefully guarded by protocol and padlocks as the Library chimes, lest the clumsy intruder alarm the little men who live there and who will, if the proper handles are yanked, blow trumpets, tilt tables, and laugh like a human voice. Usually, however, they venture no din more startling than the deep, shivering grunts of a full diapason, whereas outside, in the belfry, a half-dozen freshmen turned loose to sound the tocsin can dismay the stoutest hearted citizen or pigeon with a dreadful clangor. Nearby, the topmost turret room of the Museum stands swept and ungarnished above its winding, rat-riddled stairs with never a stuffed fish or Confederate banner to relieve its nakedness, though once it housed all the schmutziana of the College library, in the days before one could find a more ample supply at any newsstand. And while we are on this level - physically, not metaphysically - we might wing our way over to the little radio shack huddling on the roof of Wilder where, for a moment, we can imagine ourself Jack Binns tapping out a CQD from the rammed and sinking Republic.

The attics are mostly dark and dusty, except Dartmouth Hall's, which is slick as a whistle. It has lost in the rebuilding, however, its most fascinating feature: the huge pendulum that hung in a slot let into one of the partitions. We once sat dreamily through a whole semester of Philosophy IV, watching its slow, hypnotizing swing behind a glass transom. Occasionally, John Poor would desert the comfort of the Observatory to open the pit and add or subtract a half brick to the weight, that Official College Time might pass less or more swiftly.

The charm of the Webster Hall attic is how to get there. The journey involves a variety of creeping and climbing and requires a troupe of native bearers and the establishment of base and supply camps. The actual route is a trade secret as esoteric as access to the old Phi Gam goat room, but in neither instance does the end justify the means and to travel hopefully is better than to arrive.

Tunnels, elevators, dumb-waiters, fake doors, trap doors, and the interior of cornerstones are another dish. We emerged from our tour of the depths and heights of Academe with a profound respect for Dante and the conviction that stairs are steeper and longer than they used to be.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"The Working of the Religious Element"

October 1954 By GEORGE H. COLTON '35 -

Feature

Feature"The Individual and the College"

October 1954 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Feature

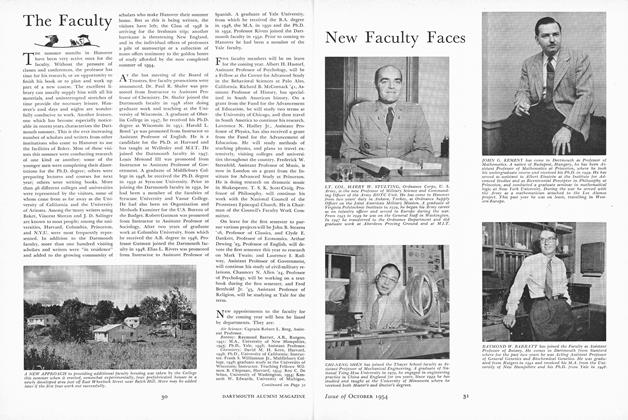

FeatureNew Faculty Faces

October 1954 -

Feature

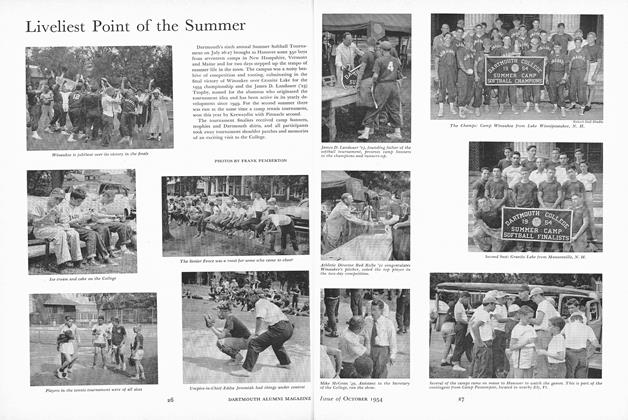

FeatureLiveliest Point of the Summer

October 1954 -

Feature

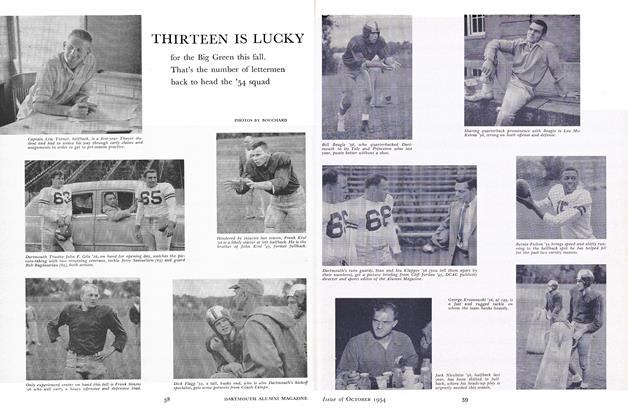

FeatureTHIRTEEN IS LUCKY

October 1954 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1954 By ERNEST H. FARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE

BILL McCARTER '19

-

Article

ArticleNot So Long Ago .... Fires

February 1934 By Bill McCarter '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

October 1952 By Bill Mccarter '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

June 1953 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

June 1954 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

June 1956 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

April 1957 By BILL McCARTER '19

Article

-

Article

ArticleENROLLMENT OF STUDENTS

-

Article

ArticleALUMNI OF MANCHESTER TO HOLD ANNUAL DINNER

December, 1923 -

Article

ArticleTHE GENUS EMERITUS, II

February 1962 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Article

ArticleSOMETHING ABOUT DARTMOUTH SONGS

April, 1910 By George G. Clark '99 -

Article

ArticleFRATERNITIES UNDER FIRE

January 1935 By Milburn McCarty IV '35 -

Article

ArticleSTUDENT WAR STRIKE

May 1935 By W. J. Minsch Jr. '36