WHEN I moved to the top floor of Lord Hall I didn't realize this guy Dick Bodley would live next door or even on the same corridor or, for that matter, even in the same dormitory. If this sounds bitter it's because I've had to listen to his loud singing now for two months. At first I wasn't sure whether I could stand it or not, but it seems I could. Dick's voice is pretty good, that I'll grant you, but it's just that he sings the same disjointed nonsense over and over again. Bodley's room is separated from ours only by a thin dormitory wall, and it gets on a fellow's nerves when he wakes up to the same ditty he went to bed to.

About the third day after we had moved in I was trying to read my sociology one afternoon but was having a tough time of it because of the chorus of foot-tappings and gurgles from next door in 407. In fact, I was about to slam my book and go tell Bodley to shut up when Harry, that's Harry Proctor my roommate, came in from his lab. I complained about the noise. He only looked at me vaguely and mumbled through regular chompings on a large red apple. As he threw his books on the sofa and started to depart into the bedroom I caught something about a glee clubber. So that was it. Dick Bodley was a glee clubber. Small consolation that was.

In the bathroom that evening Bodley was in the shower when I came in to brush my teeth. He hadn't opened the windows and the whole place was steamy and dripping. In the middle of this vaporous cloud Bodley was singing at the top of his lungs.

"Set down servant - I can't set down!" (Higher and with more agitation.) "Set down servant —I can't set down!" (Full blast.) "Set down servant - I can't set down!"

Then there followed a long wail like a sad dog baying at the moon. It was repeated, this time with foot-thumpings and an occasional off-beat slap on the wet thigh.

I rolled up the window so that the steam eddied around in clouds. With the corner of my towel I wiped a clear spot on the fogged mirror. The noise continued louder now. I would ignore it at all costs. Only fools and immature dolts went around making spectacles of themselves like that.

"Now servant you set down, set down, set down, set down, set down!" The toothpaste was just touching my lips when I could stand it no more.

"Turn it off! Pipe down! Quiet! Ya got somethin' wrong with ya - or somethin'! You're drivin' us bats! We gotta study!" I ran down like an old phonograph. But Bodley didn't seem to mind my criticism. He apologized; he was unaware that he was offensive. As he clattered down the hall be-slippered, with a towel around his waist, and dripping as he went, he called back over his shoulder in a friendly way, "That's a great number, isn't it? We're singing it this Houseparties Weekend. Don't forget to get a ticket." I was puzzled and curious.

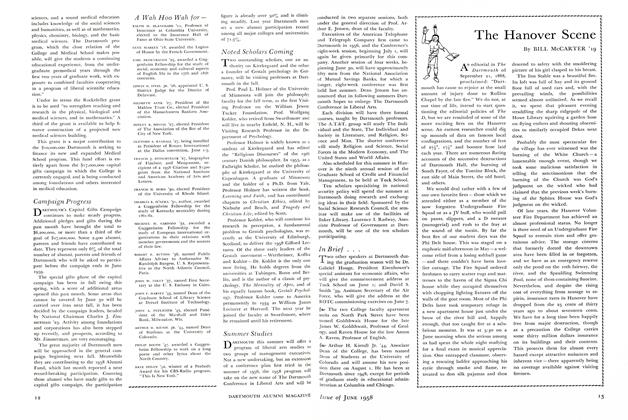

Passing old Rollins Chapel about 7:30 a few evenings back I was surprised to hear singing. It was one of those blustery rainy November nights when the clouds sweep low over the swaying black elm trees; it was hardly a time to hear music. As I looked into Rollins' ominous face I could scarcely believe my ears, so incongruous was the cheering harmony of men's voices from within. I paused a moment in a street light's shine to contemplate the wet pavement and to listen as the voices rose and fell. I decided to investigate.

Opening the door into Rollins is like stepping into some long-closed mausoleum. No other building on campus harbors such a foreign and gloomy atmosphere. The heavy door clanged shut, and I was left in the semidarkness. A musty, dank odor from age-worn floor boards, the long absence of sunlight, and the very cold nearness of so much old wood and stone would have driven me back out into the night had it not been for the beckon- ing of the music. It urged me to grope my way into the lighted nave of the chapel.

At the far end of the building, seated fanwise in a sort of circular niche beneath the arched convergence of great wooden beams, sat some fifty men of the Glee Club. They sat, as it were, in the only pool of light in that shivering reservoir of blackness, and I suppose they had been there for some time, for it appeared that this practice session was about to end. I stood a while and listened from the opposite end of the chapel. Then I sat down on one of those peculiar rush bottom seats found only in churches. The song was soft and beautiful, not at all like Bodley's annoying ditties. Yet, somehow I knew I had heard it before, undoubtedly in fragments as they had sifted through our common wall. Now, though, the song seemed so different. The director was at some pains to get just the right degree of softness and inflection. He kept stopping them. I wished he would let them finish, for as soon as they began to weave me into their song, they would have to stop again. It was hypnotizing. Every face and eye were so riveted on that one man. The suspense mounted as I watched. How many times had Bodley and the others sung that part over and over again? Though it must have been thousands, I watched them all melt into one. The song was moving on to its soft, stirring finish. There could be no break now. All animation and attention seemed frozen in the oneness of the moment. The music had reached its goal and stepped on, floating on nothing, after the directing hands had ceased their flutter. There was a silence, one golden drop. The business was over and the rehearsal finished. Guys, Bodley among them, came streaming down the center aisle towards me all noise, odd singing and laughter.

I buttoned my slicker up to the throat and went out into the rain with them. We wandered off toward Baker and the dorms. I could hear snatches of song up by Dartmouth Row, and crossing the green, and on its way to Richardson and Woodward and all the other dorms. Out of the boredom of repetitious practice a moment had been born, and they who had surprised themselves by making it were carrying it back with them through the rain to the places where they lived and studied and laughed.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePREFACE TO DARTMOUTH

December 1954 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

Feature"The Record of Their Fame"

December 1954 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25 -

Feature

Feature"They Game from America and They Were Four"

December 1954 By PROF. HENRY B. WILLIAMS, -

Feature

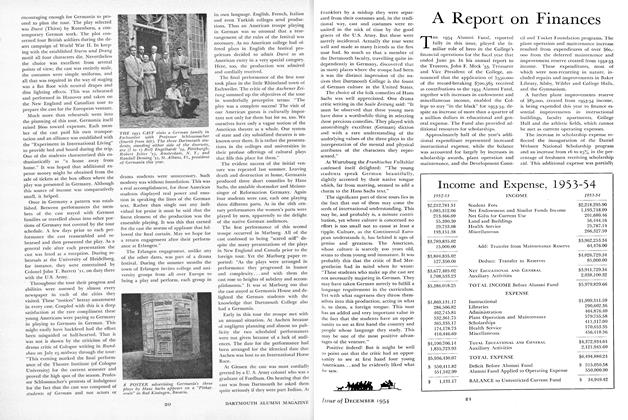

FeatureA Report on Finances

December 1954 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1954 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

December 1954 By ALEX J. MCFARLAND, CHARLES V. RAYMOND, HENRY S. EMBREE,

G. H. CASSELS-SMITH '55

-

Article

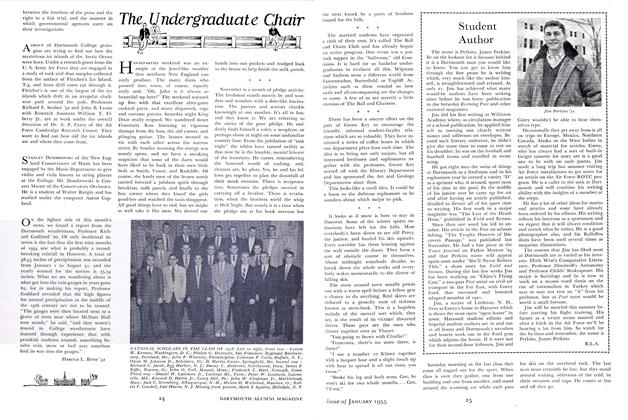

ArticleThe Undergruduate Chair

January 1955 By G. H. CASSELS-SMITH '55 -

Article

ArticleThe Underĝraduate Chair

February 1955 By G. H. CASSELS-SMITH '55 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1955 By G. H. CASSELS-SMITH '55 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

April 1955 By G. H. CASSELS-SMITH '55 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1955 By G. H. CASSELS-SMITH '55 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1955 By G. H. Cassels-SMITH '55

Article

-

Article

ArticleWEBSTER'S FRATERNITY PIN PRESENTED BY C. K. FIELD

DECEMBER 1926 -

Article

ArticleMen of 1942: What Can I Do?

August 1942 -

Article

ArticleA Wah Hoo Wah for

June 1958 -

Article

ArticleLOOK WHO'S TALKING

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By Claire Groden '14 -

Article

ArticleA Recent "New Yorker

May 1934 By S. C. H. -

Article

ArticleWith the D.O.C.

April 1942 By Warren E. Preece '43